St. Patrick’s Day is coming up and you know what that means… a shamrock shake at Starbucks, featuring those well-known Irish ingredients: vanilla, mint and green tea. And then there’s the Paddy’s Day merch: shamrocks again. If the Princess of Wales as colonel of the Irish guards turns up to celebrate the day, she’ll be sporting a sprig of it the size of a small broccoli.

What could be better as a symbol of all things Irish than this botanical metaphor for the Trinity? Because, as we all know, it was St. Patrick who, to describe the triune God to the native Irish, picked a shamrock to demonstrate the Three Persons in one God. The point was lost on the authors of one children’s book on St. Patrick I picked up in Dublin airport, which declared that what the shamrock showed was there were three gods in one, which is a) heresy and b) proof of what happens when nuns leave the education system.

There is in fact no consensus about what a shamrock is, other than it’s a trefoil and a species of clover. Most people correctly favor trifolium dubium, or lesser clover, with a minority opting for the white clover, trifolium repens, and a few for trifolium pratense, or red clover. The word simply derives from the Irish for young clover or rather, little three-leaved plant. One spoilsport botanist from the National Botanic Gardens observed: “In one sense, there is no such thing as shamrock, no single uniquely Irish species.”

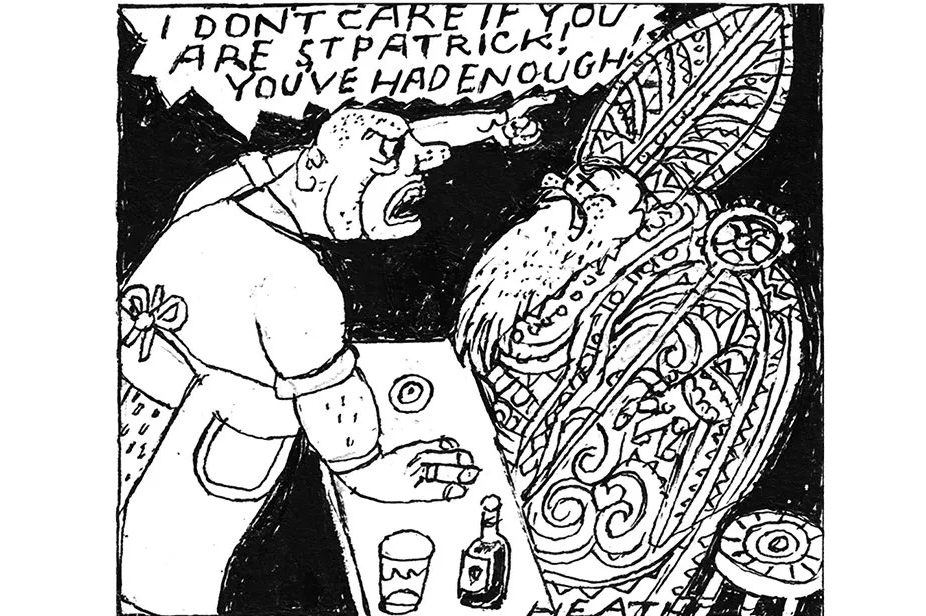

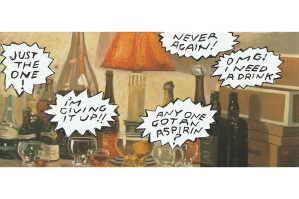

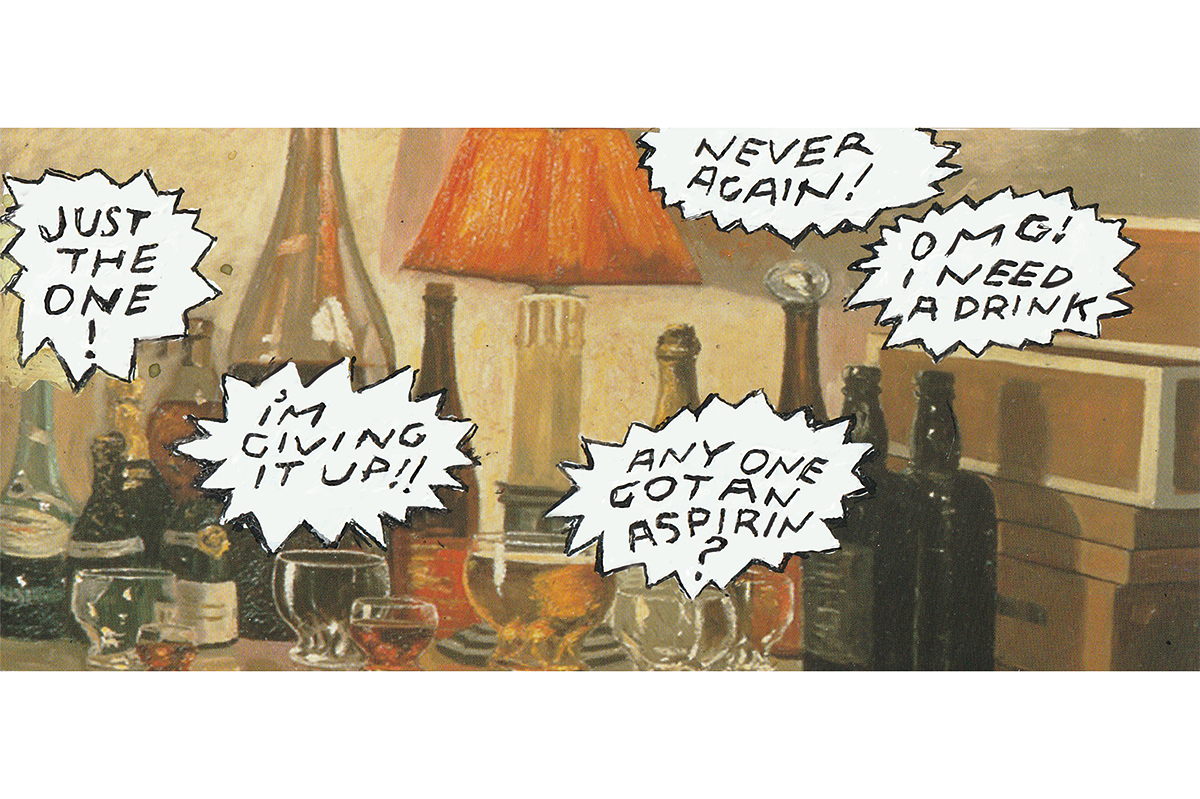

The oral tradition associating the shamrock with St. Patrick’s teaching on the Trinity is impossible to date and could indeed be founded on reality. The first written association between the shamrock and the Trinity comes in a 1726 account by the clergyman-botanist Caleb Threlkeld: “This plant is worn by the people in their hats upon the seventeenth Day of March yearly, (which is called St. Patrick’s Day). It being a current tradition, that by this Three Leafed Grass, he emblematically set forth to them the Mystery of the Holy Trinity. However that be, when they wet their Seamar-oge, they often commit excess in liquor, which is not a right keeping of a day to the Lord; error generally leading to debauchery.”

Debauchery, or certainly drunkenness — undoubtedly a part of St. Patrick’s Day — was a useful way to escape the rigors of Lent. He refers here to a lost custom of drowning the shamrock which entails taking it from your lapel or hat and putting it in the last glass of the day. When you’ve drained it, you dig the shamrock out and toss it over your left shoulder, presumably to get the devil in the eye.

Some Elizabethans observed that the Irish ate shamrock, though they were probably confusing it with wood sorrel. In 1681, an English traveler observed that “the seventeenth day of March yearly is St. Patrick’s… when the Irish of all stations and conditions wear crosses in their hats and the vulgar superstitiously wear shamroges, three-leaved grass, which they likewise eat (they say) to cause a sweet breath.”

There’s a new one…shamrock as breath-fresheners. At the end of the great day, eat your sprig and see if it banishes the aroma of Jameson.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply