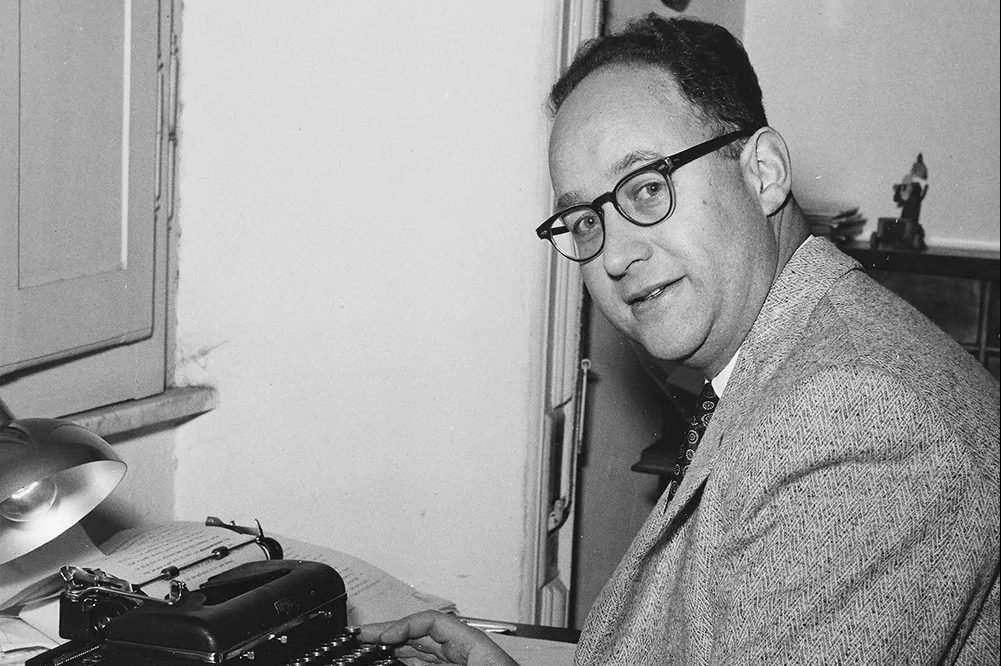

“Art begins in a wound, an imperfection,” said the late novelist John Gardner, one of the last American writers to grow up on a farm, “and is an attempt to either learn to live with the wound or to heal it.” Gardner’s wound was more gaping than most: on April 4, 1945, the eleven-year-old was driving a tractor hauling a two-ton roller called a cultipacker. His six-year-old brother Gilbert fell from the tractor’s hitch. John turned around just in time to see his brother’s skull crushed under the huge implement. (Marge Cervone, a Gardner family friend, told me that “Gilbert was the kind of kid who would never hold on.”)

“He was not to blame,” said John’s mother. “Nobody could have stopped that thing happening.” Although the adult Gardner would cauterize this wound with his best short story (“Redemption”), his mother’s comforting words could not stop the blinding flashbacks that tormented him during his all-too-brief life.

If “home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in,” in Robert Frost’s phrase, home is also the place where writers who fall out of fashion must land and find posthumous succor. John Gardner isn’t even among my 100 favorite writers, but he is ours, and we owe him remembrance.

So every year since 1996, on an invariably chilly evening in late October, a far-flung score of folks have gathered in Gardner’s (and my) hometown of Batavia, New York, to read from his works, discuss his legacy and collectively fall short of his typical alcohol intake.

When the Pok-A-Dot, Gardner’s favorite diner and long-time host of this shaggy and convivial affair, lost its counter to a Covid renovation, the event shifted to the Kauffman living room. (I wish we could replicate the Pok-A-Dot’s tantalizingly greasy aroma, but we do have a nicer bathroom.)

This year we had eleven lectors and an equal number of listeners. Readers who drove in from Ohio, Pennsylvania and Indiana (four) exceeded those raised in our county (two), but then writers, like prophets, are seldom honored in their hometown, where everyone knew them when. (To outsiders, Gardner was a long-haired, womanizing gearhead, but at Batavia High he was a French horn-playing band geek.)

Several readings ago I spoke the poem John wrote days after the accident. Its first and last stanzas went:

In two feet water my brother would wade/ He'd do it, All knew it/No wilder imp was ever made/'Twas true! God knew!.... With a will he shot at work and play/ Laughing, singing, always gay/But once he laughed and played too far!/His jolly songs no longer are.

I meant to reprise that this year but just couldn’t bring myself to do it. Instead, I read from a 1977 interview published in the Atlantic. It contains Gardner’s classic description of his politics, very much in the Burned-Over District tradition of Upstate New York: “I am on the one hand a kind of New York State Republican, conservative. On the other hand, I am kind of a bohemian type. I really don’t obey the laws.”

I also read Gardner’s summation of what he called “moral fiction,” the take-no-prisoners expression of which earned him the enmity of celebrity writers (Joseph Heller, John Barth) who had never known Gardner’s generous spirit, helpfulness to young writers and the basic decency threaded through his helter-skelter life:

“If we celebrate bad values in our arts, we’re going to have a bad society; if we celebrate values which make you healthier, which make life better, we’re going to have a better world. I really believe that.”

John Gardner once said, “I think a writer who leaves his roots leaves any hope of writing importantly,” and although as an adult he was a typical academic nomad, in death he came home.

He was killed in September 1982 when his Harley wiped out on a curve in Susquehanna, Pennsylvania. (Grace Kelly died the same day, knocking his expiry off the front pages). Like Gilbert — and Princess Grace, come to think of it — John died a victim of a motorized vehicle mishap.

Church organist Ann Emmans told me that his was the most hymn-filled funeral service she ever played. Ann pounded out standards like “The Old Rugged Cross” as his neighbors bid farewell to John Gardner the duty-driven Presbyterian, the vodka-soaked logorrheic, the philosophical novelist who loved Chaucer and Walt Disney: the walking contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction, as the Kris Kristofferson line goes.

His family said he never stopped blaming himself for Gilbert’s death.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply