A pot roast is probably the antithesis of glamorous cooking. But that’s also sort of the point. For as long as we’ve been cooking meat, we’ve looked for ways to make the tougher cuts more tender and succulent. It’s the kind of cooking that every culture around the world has developed individually, a way of transforming the cheap and possibly unappetizing into something delicious. The answer is simple, and relies on three elements: low heat, moisture and a lidded cooking vessel.

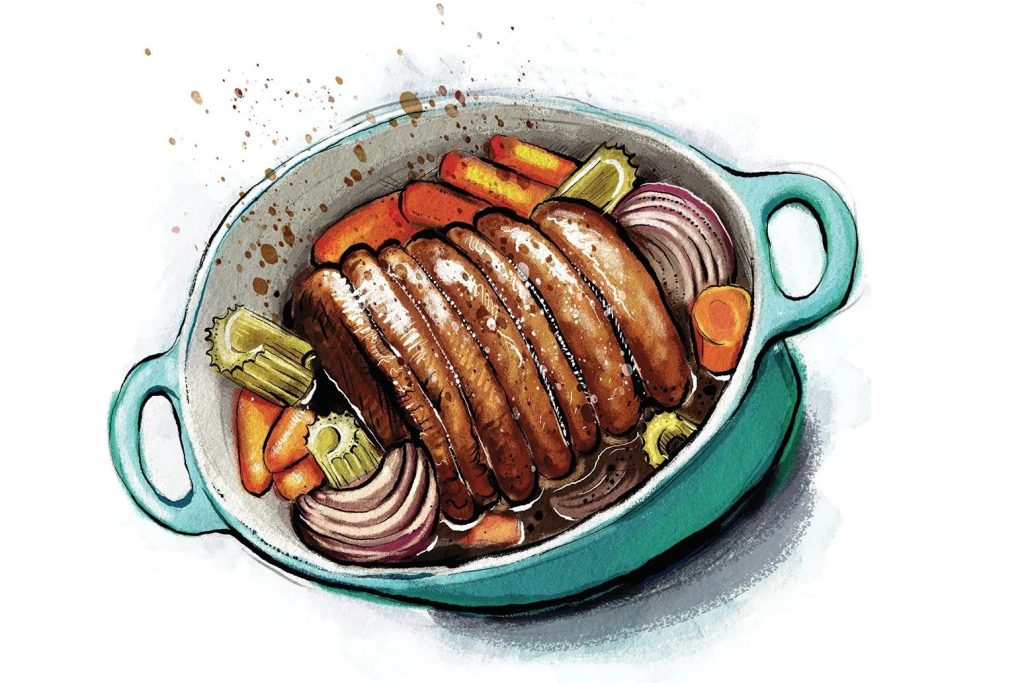

A homely and economical way of bringing the best out of an unprepossessing joint

Pot roast is the American way of slow-cooking whole joints of unforgiving meat, usually a piece of beef (although similar principles apply to pork and lamb). But this kind of cooking is not confined to the US, and really, I am using the term “pot roast” as a shorthand for any kind of slow, indirect, enclosed cooking. The same techniques are found in German Sauerbraten, Cuban ropa vieja, and the French pot au feu — where the meat and vegetables are poached together but served as two different courses.

These cuts are cheap because they are harder to handle: they need coaxing and proper cooking time to prevent them from being dry or chewy. The cuts come from areas of the animal that have worked harder during the animal’s life, so the muscles are made up of tougher fibers, and the connective tissue between them takes longer to break down. Done properly, they should be so soft you could cut them with a spoon, and should sing with deep, complex flavor.

Indirect cooking is a far gentler way of cooking than searing or roasting. But it’s fair to say that the result is not a looker. Braising or poaching does not confer color or grill marks; there is no golden rendered fat, crisp at the edge. The meat loosens rather than tightens and the vegetables may lose their verdancy. The slices that come from a pot roast are not neat and thin; there is no coy blush of pink at their center; they may even fall apart. The end result is a large piece of brown meat in a thin brown sauce.

At the same time, it is the simplest and perhaps most satisfying of kitchen transformations: a cheap, tough piece of meat and some workaday veggie transfigured into a meltingly tender one-pot dish through the application of gentle heat and time. It is a homely and economical way of bringing the best out of an unprepossessing joint, an all-in-one method of cooking that produces wonderfully succulent meat, yielding veg and a gravy.

There are ways of mitigating any aesthetic downfalls. Browning the meat at a higher temperature first, before the liquid and lid are added, helps. This high heat causes the Maillard reaction on the surface of the meat which creates flavor molecules that aren’t otherwise present, and these in turn result in a richer, deeper flavor that will improve both the meat itself and the sauce. This brings color, stops the joint of meat falling apart and improves the taste.

Cooking in a lidded pot also means that the sauce or gravy doesn’t reduce: you will not automatically end up with a French-style high-gloss demi-glace or jus. If you would rather something that more resembles a traditional gravy, you can drain the meat and vegetables, covering them to keep them warm, and rapidly reduce the cooking liquor. Or for an even more robust sauce, make a quick roux with equal parts of plain flour and butter in a pan (about 1/5 cup of each), heating them until they sizzle, and then whisk in the cooking liquid. This will thicken the sauce, and you can then return it to the pot or pour it over the sliced and served meat. But I rather like the almost brothy texture of the untouched liquid, though I know my messy limits and serve it in wide, lipped bowls with lots of bread for dunking.

Pot roasts are unlikely to become features of restaurant menus any time soon: they lack the finesse of a rare flat iron, or the gleam of a Bordelaise-covered chateaubriand. Their Instagrammability is close to nil. But when it comes to comfort, flavor and texture, they are home cooking at its finest.

Serves 4 Takes 10 mins Cooks 3 hours

- ¼ cup butter

- 1 tbsp olive oil

- 7 oz red wine

- 14 oz beef stock

- 3 onions, peeled and cut into wedges

- 5 carrots, peeled and halved

- 3 sticks of celery, halved

- 2.6 lb beef silverside or topside, rolled and tied

- Preheat the oven to 325°F/300°F fan. Heat a large, oven-proof casserole dish over a medium-high heat, and add the butter and oil. Generously season the joint of beef with salt and brown on all sides. Take your time here, as a lot of the flavor comes from the browning.

- Nestle the onions, carrots and onions around the beef, and add the red wine and beef stock. Bring up to a simmer, cover with a lid, and transfer to the oven and cook for three hours.

- Lift the meat from the dish and place on a large serving board. If you plan to reduce the cooking juices, also lift out the vegetables and place in a covered dish. Reduce the cooking juices to your taste, and check for seasoning. Carve the meat and return it to the vegetables and juices, or serve separately.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply