In the middle of an unpredictable Indian summer, here is a recipe from sultry southern Italy, which is suitable for the changing seasons. While parmigiana di melanzane was born of hot Italian summers, it is also perfect for autumn, as the days shorten and darken. There is inherent comfort in the hot, almost-melting eggplant, covered in a rich sauce and blankets of cheese.

The name is possibly a red herring, possibly not. Eggplant parmesan is most associated with Naples, and is also beloved in Sicily and Calabria. Many have found it hard to reconcile a dish that supposedly comes from the southern regions — where eggplants were most readily grown — with it being named after a northern Italian cheese. Several food historians have put forward mishearings or mispronunciations to explain the contradiction.

According to Mary Taylor Simetti, who specializes in Sicilian cuisine, the “parmigiana” apparently does not refer to the parmesan in the dish — which is one of the reasons I feel happy to scatter vast quantities of mozzarella throughout the layers — but instead is a bastardization of the Sicilian word “palmigiana” which means shutters, referring to the overlapping and interleafing of the eggplant as you create the layers. The Sicilians, she tells us, struggle to pronounce the “l,” and often substitute it with an “r.” It’s a charming, slightly romantic story, but historian Clifford Wright takes more of an Occam’s razor approach: by the 14th century, parmesan cheese was widely traded throughout Italy, so it’s entirely plausible that it could have lent its name to the dish.

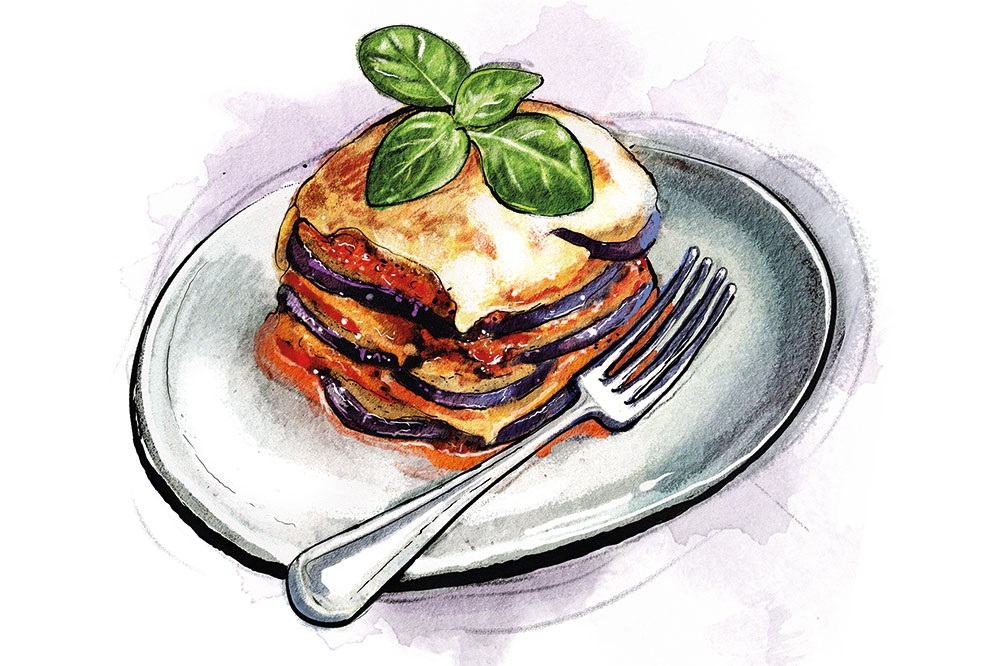

When it comes to the culinary elements, these are far more straightforward. In fact, it’s a pretty minimalist dish: eggplant, tomato sauce, mozzarella and parmesan, all layered together until they meld and transform into something greater than the sum of their parts, the cheese clinging to the eggplant and melting in the lower layers, while bubbling and bronzing on top. It’s not a terribly quick dish to make, but it’s also not a difficult one: a sauce is simmered on the stove for three quarters of an hour, until the one-dimensional tomatoes become complex and deeply flavored. Lots and lots of eggplant slices fried in batches, until it feels like you have enough to construct a house, then dealt out like playing cards to form seamless layers. And cheese, torn or finely grated, distributed throughout, before the whole thing is baked together until it is golden and gooey.

In the preparation, I trust the Rome-based food writer Rachel Roddy implicitly, and I have taken two lessons from her in my eggplant parmesan. First, to create the velvety, rich texture that is so irresistible, so distinctive in an eggplant parm, you must deep fry the eggplant. You can, of course, brush it puritanically with a little oil and roast it. But it won’t be quite the same: the eggplant will never have the same luscious interior, the silky outside that deep-frying brings. Shallow frying, while it seems relatively abstemious, is a false economy: deep frying cooks at a higher temperature, meaning that the eggplant cooks very quickly, which reduces the amount of oil absorbed.

Secondly — and even if you don’t follow me on that first point, you must on this one — once you have baked the dish, you absolutely, categorically must leave it to cool, and then reheat it before serving. It’s the same principle as lasagna: it needs time to become its best self. If you serve it straight out of the oven, it will fall apart on the plate. Those layers you worked so hard to achieve will cascade, like the birthday cake the good fairies make in Disney’s Sleeping Beauty, sliding ever downwards. Letting it cool, and then reheating it, means it will retain its structural integrity much better.

Serves 4-6

Cooks 30 mins

Takes 1 hour, 30 mins (plus cooling)

- 1 400g can of tomatoes

- 3 cloves of garlic, peeled

- 1 tsp sugar

- 1 tsp dried oregano

- Handful of basil leaves

- 4 large eggplants

- Vegetable oil, for frying

- 300g mozzarella, torn

- 100g parmesan, finely grated

- First, open the mozzarella and put it in a sieve to drain while you prepare the rest of the dish.

- Make the sauce. Heat the tinned tomatoes, garlic cloves, sugar, oregano and basil, bringing the whole thing up to a gentle simmer. If the tomatoes are whole, squish them thoroughly against the side of the pan with the back of a wooden spoon. Reduce the heat to low and cook for forty-five minutes, occasionally stirring to prevent it sticking. Squish the garlic and remove any big bits of basil.

- Slice the eggplant into thin rounds, about a quarter of an inch thick. Heat a pan or deep fryer with two inches of oil, until the oil is moderately hot (350°F). Fry the eggplants in batches, draining each batch on a paper towel.

- Preheat the oven to 350°F. In a large, oven-proof dish, layer the different components: first slices of eggplant, slightly overlapping, then a third of the tomato sauce, followed by a quarter of the mozzarella and parmesan. Repeat twice more, then top with a final layer of eggplant, and scatter with the remaining cheese.

- Bake for thirty minutes, then set to one side to cool for at least three hours, refrigerating once cold.

- When you’re ready to serve it, reheat the dish at 350°F until it’s hot (for ten minutes to about half an hour — the timing will depends on how long the dish has had to cool), then pop it under the grill for a moment until the cheese is bubbling.

Sign up for Olivia Potts’s bimonthly newsletter, which brings together the best of The Spectator’s food and drink writing, here. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.