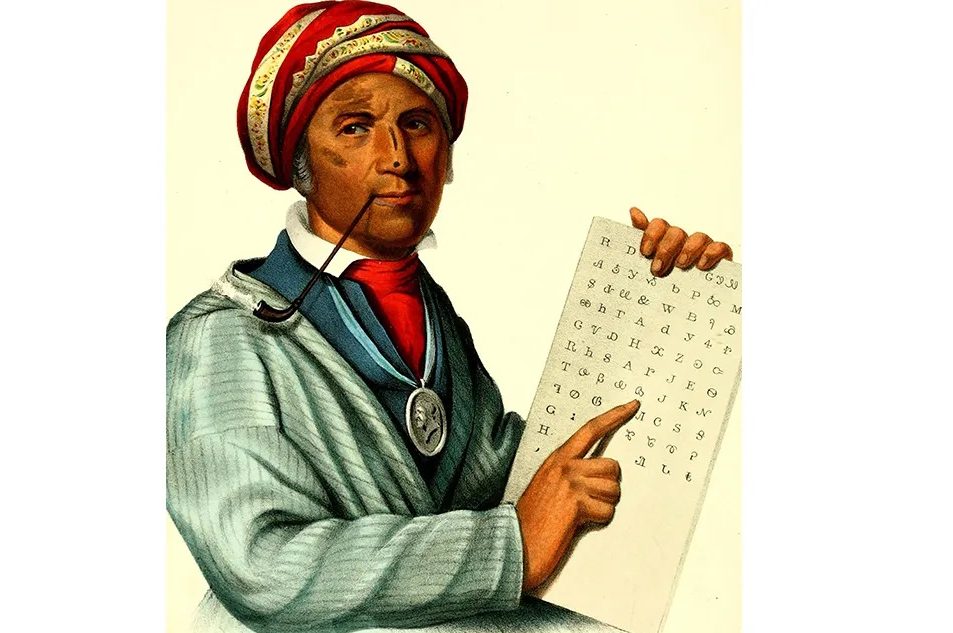

Next to the Harvard Club in Boston’s Back Bay stands the old Eliot Hotel, named after Harvard’s most famous and probably most influential president, Charles William Eliot. The hotel was built in 1925 as a genteel way of easing aging Harvard professors into semi-retirement. In 1939 it was purchased by a private family and became one of the city’s finer hotels, with many amenities including a top-of-the-line Uneeda Shine-O-Mat. Any well-dressed gentleman striding out onto Commonwealth Avenue would be embarrassed to show a scuffed wingtip, and shoeshine boys were not exactly welcome in that part of town. The Shine-O-Mat, installed in about 1947, solved the problem.

The Eliot Hotel had its ups and downs over the years. Sometime in the early 1980s, the owners cleaned house, ridding themselves of furniture that had grown fusty and, in a moment of historical heedlessness, consigning the Shine-O-Mat to a near brush with junkdom.

Gentlemen readers of a certain age may recall the glory days of Uneeda Shoe Shine Machines, once a staple of drug stores and barber shops. Those versions were coin-operated (“Fast — Convenient”) and for twenty-five cents could put a gleam on your vamp and a smile on your face. The Shine-O-Mat was the upper-crusty version of Uneeda’s product line, suitable for venues such as the Eliot.

It consists of a large silver-colored metal box containing a durable motor that drives two spinning brushes, conveniently labeled black and brown, perhaps to assist the patron who is a little squinty-eyed from having one too many French 75s the evening before. (Note to those who need a refresher on 1940s cocktails: dry gin, Champagne, calvados, grenadine and lemon juice, named after the French 75-millimeter field gun in World War One.)

The Shine-O-Mat is not a piece of equipment that was likely to go wandering off. It weighs upwards of 100 pounds. It is as sturdy as Plymouth Rock and likewise served as the foundation of respectable society, when there was such a thing. Of course, by the 1980s, men were wearing athletic shoes and boots to work, boat shoes, loafers and campsides. Air Jordans arrived in 1985.The preppy look had no need for a shine, which would have implied a fastidiousness out of keeping with the relaxed self-confidence of the era.

What saved the Shine-O-Mat from the fate of tie pins and cufflinks was a university administration stubbornly devoted to the standards of yesteryear. John Silber was the president of Boston University — and he was a man resolute in his determination to defeat what would soon be called political correctness, but which he denounced as “short-pants Marxism.” Silber, appointed as BU’s president in 1971, had made a name for himself and his institution by opposing most of the intellectual fashions as well as the actual fashions of his day. And he gathered around him like-minded cultural recusants, one of whom was Sam McCracken.

Sam was an eloquent writer and the eye of his own personal hurricane. You could find him in his brownstone office on Bay State Road surrounded not merely with heaps of papers, but with hundreds of antique cameras and the innards of disassembled everything. It was Sam who spotted the Shine-O-Mat on its way out of the Eliot Hotel and who rescued it to install in John Silber’s administrative building. Just why he did this, I’m not sure. Sam had a speech impediment that made him hard to understand, but he did succeed in conveying the idea that properly shined shoes were the mark of a properly organized man. How this comported with his personal habits I was unclear. Sam had other dicta to live by. “Gentlemen do not use thesauruses,” he declared. And he would use no encyclopedia after the 1910 eleventh edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. He was a very large and often unkempt man, but one whose shoes impeccably gleamed.

In any case, from the mid-1980s to 2004, the Shine-O-Mat sat securely in the presidential quarters of Boston University, where I also worked. I understood the presence of the machine in the executive men’s room to be a sly appropriation of the legacy of Charles William Eliot, the only university president that Silber might have conceded was his intellectual equal. Eliot was one of the great savages in American higher education — the man who introduced “electives” in the Harvard curriculum and set in progress the eradication of nineteenth-century ideals of classical education. The elective system was a wrecking ball that eventually leveled the gothic hierarchy of courses that ensured that all college graduates had climbed the hierarchy of human knowledge to a modest degree.

Eliot believed instead in importance of “practical training” and favored education at every level that contributed to the progress of American industry. Appointed as Harvard’s president at the age of thirty-five in 1869 and serving until 1909, he elevated Harvard to its position as one of the world’s most renounced universities. He also undertook a major effort to reform Boston’s schools. Silber, in effect, said, “Hold my beer,” and undertook the “Chelsea Project” to transform the public schools in the impoverished town across the Mystic River from Boston. Boston University did indeed vault ahead under Silber’s leadership, but it fell far short of the mark he had set.

And I know why. In 2004, Silber moved his administration out of its lovely brownstone quarters on Bay State Road, to a penthouse suite atop then new School of Management building. The move occurred with Silber’s characteristic abruptness. One day he ordered everyone to drop everything and report immediately to the new quarters. No one was allowed to return, and 147 Bay State Road became Pompeii minus the volcanic ash. Someone cut the power and locked the doors. Among the things Silber left behind was the Charles Eliot memorial Shine-O-Mat.

Oh, and me. BU was in a state of turmoil after the sudden resignation of Silber’s successor, Jon Westling. I was Westling’s chief of staff. Silber may or may not have engineered Westling’s departure, though I think it likely. In any case, Westling, his secretary Joanne and I were left in a crow’s nest office in an adjacent building. One day, Joanne and I, armed with flashlights and a wagon, ventured into the ruins to see what we could salvage. The Shine-O-Mat was our principal haul.

I disagree with those who say that the spirit of Charles Eliot — the spirit of the man who idolized American industry and prosperity and saw a profound connection between those ideals and American education — is embodied in the Shine-O-Mat. But it is true that the whir of the two great buffing wheels evokes the energy and confidence of that great educational innovator.

The Bay State Road offices were left to a clean-up crew who set about hauling off the debris to the dumpsters. But I had rescued the Shine-O-Mat — and in the years that followed, I dragged it with me from job to job, from my time as provost of the King’s College to my current role as president of the National Association of Scholars.

John Silber’s long career came to an ignominious end not long after he abandoned the Shine-O-Mat. The board of trustees ditched him after he botched an effort to install a new successor. The King’s College, not so incidentally, has lost its accreditation and appears set to close for good. The National Association of Scholars is thriving, but the Covid exodus of staff all over the country has left me with a New York City office many times too large. We plan to move to smaller quarters — and once again the Shine-O-Mat is at risk.

But having seen what happens to institutions that treat the machine with too little respect, I am making provisions. The Uneeda Shoe Shine Machine Corporation, under the supervision of Samuel Sacks, built its equipment a few blocks from my current office, but I’ve checked: like Thomas Wolfe, the Shine-O-Mat can’t go home again. Right now my plan is to donate it to a restaurant in New Jersey where it will continue to brighten shoes and enlighten lives for decades to come. I wish I could say the same about American higher education.