Growing up in a “mixed” American household, of Indian, Puerto Rican and Italian descent, was deeply confusing during my formative years. I came of age in a mostly white suburb just outside New York City. In addition to my foreign-sounding name, I looked nothing like any of my classmates or the kids around the neighborhood. My olive skin, bushy eyebrows and curly hair were more reminiscent of children you’d find in the more ethnically diverse neighborhoods of Queens or the Bronx.

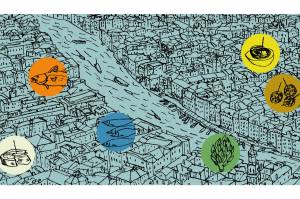

My family spent most of our weekends visiting family and doing our grocery shopping in such areas. The array of ingredients that my Puerto Rican and Italian-American mother, Loretta, was searching for didn’t exist in our local Pathmark. But the bodegas and markets in the Big Apple were like treasure chests, each belonging to a specific immigrant group and stocking their specialty produce. Once we returned home with our shopping bags, those raw ingredients came alive in our modest little kitchen.

On Saturday mornings, Mom made my favorite spin on a traditional American breakfast: two sunny-side-up eggs, a dollop of savory raita yogurt, a spicier version of home-fried potatoes and lolis, a round, fried flatbread unique to the Sindhis in northern India and Pakistan. My father, Roop, grew up in Mumbai where his mother, Gopi, used to make lolis for him as a child. When he married my mom in 1981, Gopi passed down the recipe to her new daughter-in-law. Nothing was written down, just demonstrated: pinches of “this” and “that,” a wooden pin for rolling the dough and dropping the lolis into a pan of oil to achieve the properly crisp finish.

My mother learned to master this bread, along with countless other Indian dishes, thanks to advice from other cooks in Queens’s Jackson Heights, as well as pioneering author Madhur Jaffrey and her cookbooks. But when it came to our special weekend breakfast, there was nothing better than the basic, hand-rolled bread soaking up the egg yolk.

I miss those early years, where that old childhood home served as my sanctuary from a world that didn’t understand me or my racial complexities, and where my relationship with food helped me to understand the richness of the cultures that claimed me.

While working on my debut memoir, Colorful Palate: A Flavorful Journey Through a Mixed American Experience, I interviewed my mother and wrote down her recipes, as well those of her mother Elsie. Remarkably, she remembered how to prepare each dish.

During the interview process, she found herself missing the task of cooking for my brother Ravi and me. One Saturday last spring, she decided she’d recreate our beloved breakfasts for us. But getting her hands on atta, an Indian whole wheat flour, was suddenly impossible.

Last May, India decided to ban all wheat exports due to a record heatwave that destroyed its crop as well as unprecedented circumstances that drove domestic prices to an all-time high. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine a few months earlier had meant that the global supply of wheat had plummeted and threw India, the second-largest wheat producer, into a tailspin of unregulated exports and domestic inflation.

On our side of the world, atta became completely unavailable. My mother panicked. How could she not make her special breakfast for her boys? She asked almost every store owner on her routine visits to New York to visit relatives, as well in central Florida where she now resides (like many parts of the US now, it boasts a small Indian- American community). She was out of luck. At one point, my dad found out that one of his friends had a stash of atta and was selling it by the ziplock bag. My mother considered flying up to New York and back down to Florida, carrying the bags tucked in her suitcase, but the entire operation sounded too conspicuous. She wasn’t a dealer or mule. She just wanted to roll some dough.

For many months, she gave up on the hope of making loli. Then one day, she found a small bag of atta sitting on a table in one of her Indian grocery stores. She couldn’t believe it. She quickly purchased the bag, clutching it like a baby.

On our next visit, our family was treated to our Saturday breakfast once again. Mom appeared content as she rolled the dough and dropped each perfect circle into the frying pan. I broke off a piece of the bread and used it to mop up the golden yolk. Mom smiled as she watched me eat. Life felt complete, if only for that moment in time.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2023 World edition.