The women’s soccer World Cup will kick off in under fifty days’ time in Australia and New Zealand, and England is among the favorites to lift the trophy. But who will get to see it? Broadcast deals have yet to be signed, seemingly because bids from several European countries are unacceptably, some would say insultingly, low.

Italy has reportedly offered less than 1 percent of what its broadcasters paid for the men’s event in Qatar last year — which didn’t even feature Italy — and Germany just 3 percent. FIFA are reportedly furious about these “slap in the face” offers and have threatened a blackout. Infantino says that broadcasters had offered just $1 million to $10 million compared to the $100-200 million for the men’s tournament. The sports ministers of five countries have intervened with a joint statement calling for an agreement to be reached.

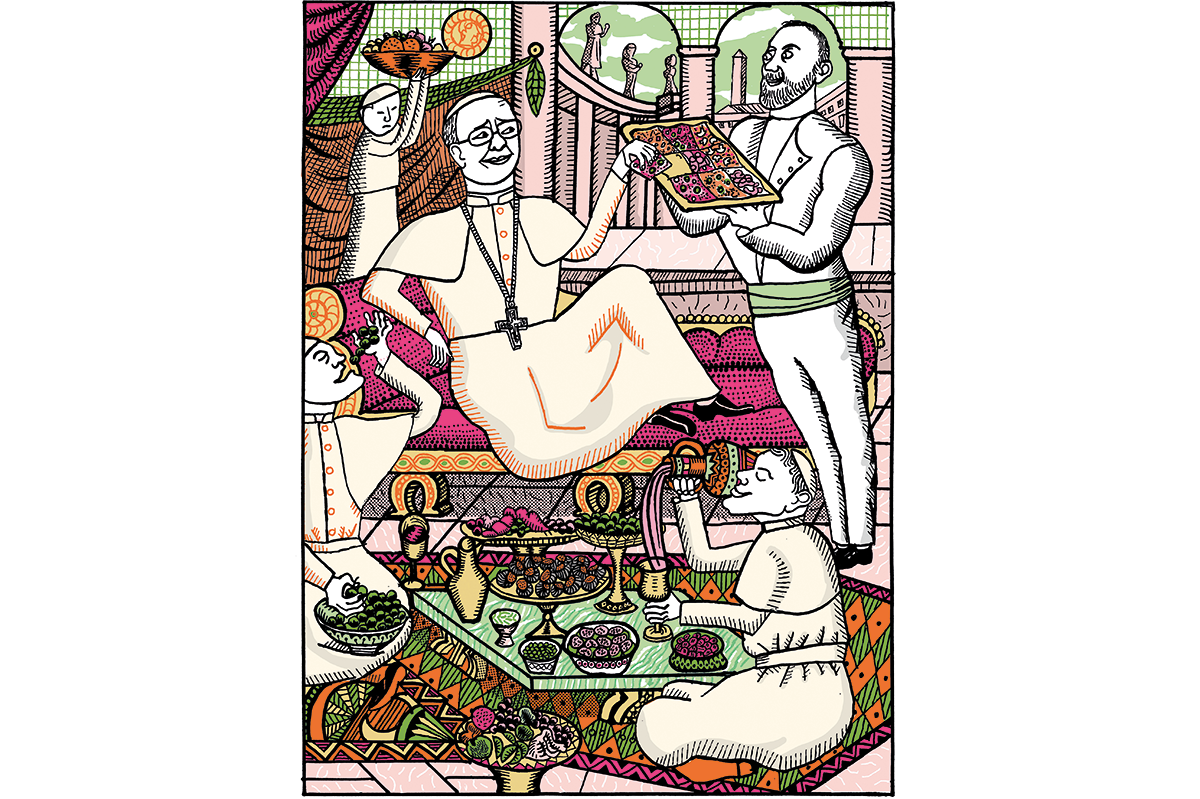

Gianni Infantino can rant and rave and threaten a blackout, but he can’t really argue with the law of supply and demand

Why are the bids from Italy and Germany so low? Women’s soccer has attracted large audiences in Germany before, but only for conveniently scheduled big one-off games — such as last year’s Euros final against England. Timing is one thing: the upcoming women’s World Cup will mostly happen when people are at work, or away on vacation, so viewing figures, especially for games not involving the Italian and German teams, are likely to be extremely low. Add in a difficult financial situation with budgets already strained by the upcoming and far more established Rugby World Cup and it’s not hard to see why European broadcasters have chosen to skimp a bit on the WWC.

We may be witnessing a revelation then, the true commercial worth of women’s soccer, and it is, soberingly, a fraction of the men’s game. This would be a truly acid pill for the game’s authorities, long-time cheerleaders of the women’s game, to swallow. The low bids reflect the likely audience and advertiser interest in the product. Gianni Infantino can rant and rave and threaten a blackout, but he can’t really argue with the law of supply and demand, from which FIFA has benefited hugely with the men’s version of the tournament.

Nor can the sports ministers credibly expect commercial companies to pay over the odds for a product with limited appeal simply based on, as their joint statement says, “improving the global visibility of women’s sport.” To what extent should commercial or even state broadcasters care about that when they have bills to pay and stakeholders to satisfy?

The losers in all this are the players, who may work as hard on their game as many of their male counterparts but will never earn a fraction of the reward. This is not a result of women’s soccer being inferior to the men’s game necessarily, which would be a purely subjective contention. To make that assertion, you would need to define “inferior” and in many ways the women’s game would compare reasonably well (on overall excitement, fair play, goals scored and value for money, for example).

But, as the bid figures reveal, women’s soccer is undoubtedly, significantly less attractive from a purely entertainment and thus commercial perspective. The FIFA World Cup (men’s version) carries a glorious history in its train as it globetrots quadrennially. Domestically, each “big club” encounter evokes and references hundreds of others and feels like the latest installment of a rather good box set TV series that we know will never end.

In contrast, the women’s tournaments always have a feeling of novelty, of being the first iteration, a constant relaunch of a product that never quite catches the public imagination in the way its sponsors hope. Around 260 million people worldwide watched the last women’s World Cup final in France, which sounds healthy, but that figure was handily beaten by the men’s final in Qatar, which was watched by 1.5 billion.

Perhaps those who aspire to parity, or something approaching it, with the men’s game need to lower their sights. The commercially successful men’s world cups in soccer, rugby and cricket are all supported by a deep-rooted and consistently popular club game. The World Cup is the gleaming summit of a solidly constructed pyramid. Women’s soccer hasn’t established the base of that pyramid yet: attendance at Women’s Super League games in the UK averages less than 7,000.

Or perhaps women’s soccer should stop comparing itself to the men’s game at all? The finances will never equate but there may well be a place for a different version of the beautiful game. Fewer prima donnas, fewer stoppages, less play acting, less hype, players with a closer relation to the clubs they play for and the fans who watch every week. There are many ways that the women’s game could establish itself and win a passionate, and committed, if probably smaller audience than the men. Vive la difference.

For the time being though, the situation may not be fair but it can’t be made any fairer by bluster from FIFA or appeals from politicians. The truth is that though it may no longer be a man’s world, it is still a man’s world cup.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.