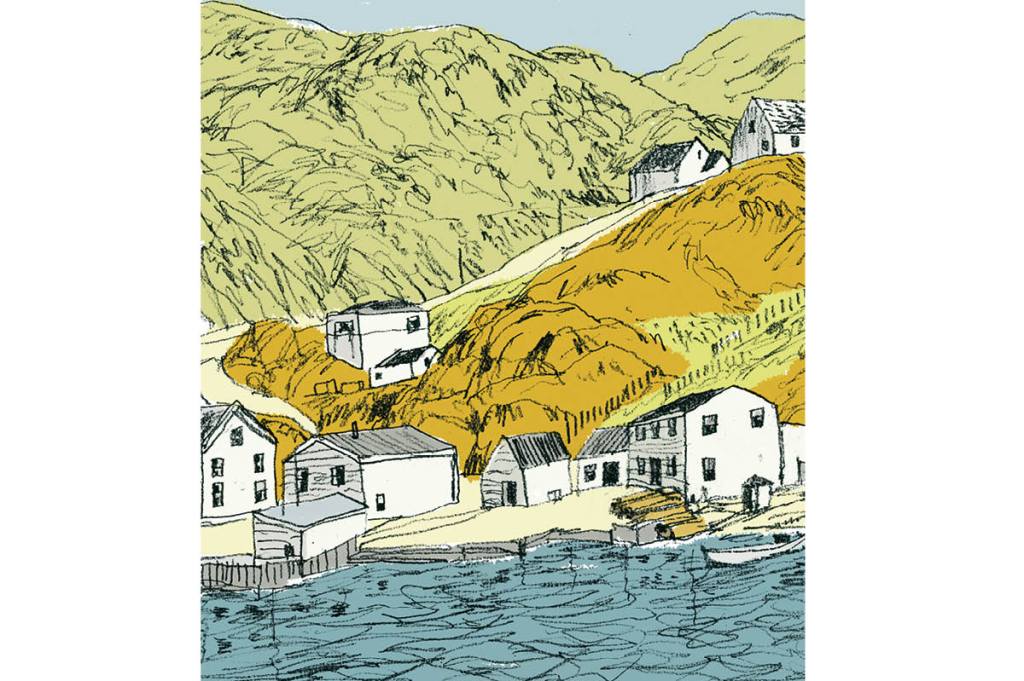

In Pilley’s Island, Canada, a tiny fishing town of barely 290 people along the northeast Newfoundland Great Whale Tour route, there’s a memorial to the area’s dead. It sits on a hillside, with a view of the rocky and wooded bay on the left, and a direct line of sight to the historic church on the right.

These aren’t any generic old dead people honored at the memorial, though. Nor is it a memorial for local war casualties (that’s up a small trail nearby) or to fallen firefighters (that’s in the next town over). No — this is a memorial to the people who have died in other terrible ways. The top of the memorial says only “TRAGIC DEATHS,” with small plaques naming each person with possibly a date and a single letter in parentheses to denote the manner of death. The key explains: “D” is for drowning, “M” for mining, “S” for sporting, “A” for auto, and “O” takes care of the others. Two of the names have an “F” next to them, which I can only assume means fire. On the other side of the memorial, there’s an inscription: This memorial is dedicated to all the people who have made Pilley’s Island home, especially those who have died tragically.

There are thirty-two deaths noted on the memorial. Most are deaths by drowning; there are “10 Members of the Swallow,” a schooner presumed wrecked in 1915 during a massive November gale across Newfoundland’s coast.

The nine towns on this small coastal spot, part of the Green Bay area, are defined by this rough sea. Without it, fishermen wouldn’t have started working these shores in 1887 alongside the miners inland; but the water is not a kind partner.

When I visited in June, the wind was whipping our little boat around; when I wasn’t fighting the chill with my jacket, I was holding the hood over my face to block the stinging rain. If I’d been driving that boat, there would have been another plaque on that memorial. (And yes, I did visit the memorial before going out on a small boat in rough weather — an unwise choice for someone with a fear of drowning, and a belief that I drowned in a past life.)

If you weren’t a miner when the towns were founded, you were a fisherman. And if you aren’t a fisherman now — or doing something related to fish and the sea — it’s hard to eke out a living. On Pilley’s Island, you make do, you move or you drown.

As you enter Triton — another town, eight minutes’ drive east — two massive warehouses, in matching shades of light ocean blue, dominate the landscape. They’re two of the largest buildings in the Green Bay area, home to Mid-Island Marine & Fabrication — a company making fishing boats, boat gear and deck equipment — owned by lifelong Green Bay resident Pete Winsor.

Winsor has seen firsthand the decline of population and industry in Triton and Pilley’s Island. As the towns shrank after the days of mining glory, locals had to pick up more and more jobs to make ends meet; and when nearby cities like St. John’s and Deer Lake took off, teeming with job opportunities, life in Green Bay started to fade.

“People want to be where the action is these days,” Winsor said. “So they move.”

As soon as residents can get jobs somewhere else, they tend to leave, and the population reports reflect that. In 2022, Canada’s census shows that Pilley’s Island had no residents between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-four. It’s just another part of unseen rural North America that is shrinking and fading out.

Those who remain usually have many generations before them in the Green Bay soil; to stay here, they work whatever jobs are available, usually more than one. Terry’s a teacher who works at the Triton Sperm Whale Pavilion. Wanda runs the Bluewater Inn and owns Bistro on Route 380, a diner and coffee shop. There’s Craig, the man who sells iceberg ice as a side gig. His days are spent as a project coordinator. Jason Roberts is both the mayor of Triton and a landlord. Captain Mike is a commercial fisherman and does boat tours in season, but he told me that even commercial fishing is drying up. Echoing Winsor, he told me that “kids aren’t interested in commercial fishing, and family businesses are dying. They’d rather move out to the cities.”

Despite his impressive buildings, Pete Winsor fits right into this multiple-income seaside crew. He also makes tombstones. They’re not carved from rock, cut and engraved to honor the dead, as they are elsewhere. They’re cut and welded together in his company’s shop, with a view of the waters that killed some of those whose lives he memorializes. As I walked through his workshop, I came across one sitting on the floor, made from a boat wheel, welded up on a stand.

Roderick Pierce Winsor, 1937-2020.

It’s for Pete’s father. The plaque has engraved images of Roderick himself, a lighthouse and a boat, and his ashes are held inside. It’ll be moved to a more appropriate location, to a spot Roderick loved, sometime soon. For now, it’s here on the cold floor.

Roderick didn’t drown like those people on the memorial, but his ties to the water ran deep. According to Pete, his father loved boats and spent every spare moment out on the sea. He felt the best way to memorialize his father was making a tombstone in the shape of his favorite activity. His father’s isn’t the only one Winsor has made, nor will it be the last. He’s currently working on two more for a pair of local teenage boys who were recently lost at sea. They’re not on the memorial yet from what I could tell, but I imagine they will be soon. That will bring the number to thirty-four.

So far, the plan is for the two tombstones to look similar to Roderick’s. They’ll be placed outside on a hill, in a memorial of their own. And instead of having ashes inside like Roderick’s, these two will have a collection of the boys’ favorite items. Their bodies were never recovered.

Maybe it’ll be a warning to the “wharf rats” — the kids who hang around the boats in the harbor, Winsor told me — to steer clear of rough waters and take heed when they go out.

In a place where everyone knows everyone and shares all the news, there’s not lots to gossip about (I ate a peanut butter sandwich for dinner one night and heard about it probably five times the next day). But as these small towns fade, their people — and their gossip — spreads out further. Craig sells his iceberg ice locally, but also in other towns, further away, and as he travels, he brings back news. And in turn, those places learn what small-town life is like; the calm of each coastal spot and the local people by the sea. Sometimes people choose to relocate there — drawn by the simplicity and the quiet and the sea — but most of the time they don’t.

Someday, Triton, Pilley’s Island and Green Bay may join the names on that plaque, drowned by a changing world. For now, though, the tide is out living in cities — and who knows when it will come back in.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2023 World edition.