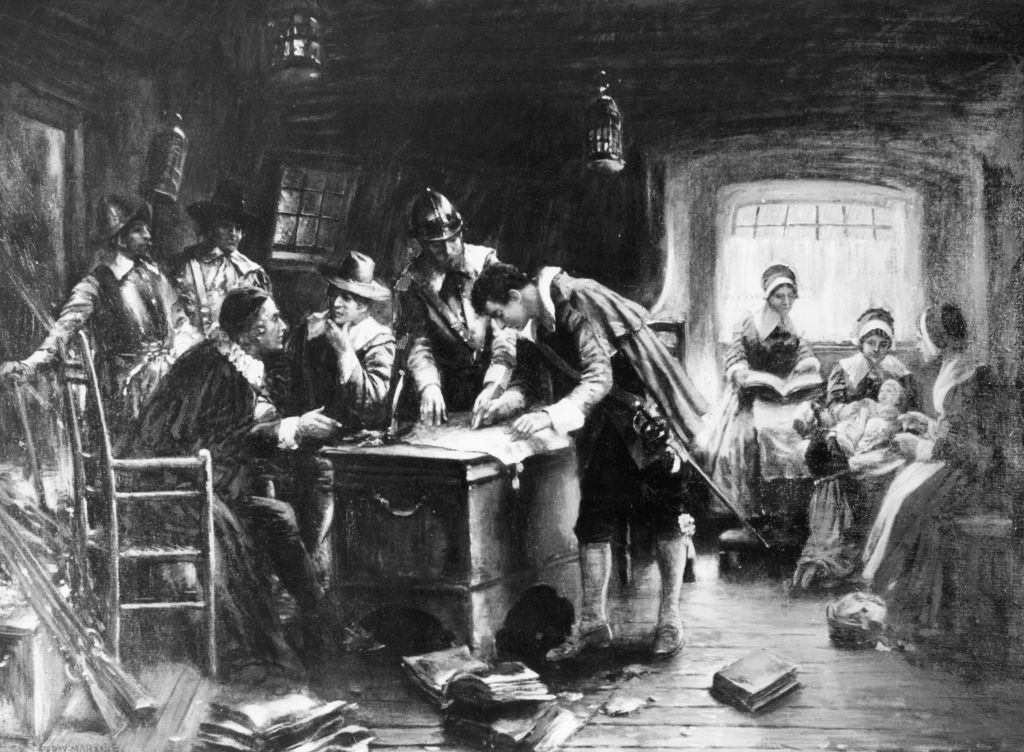

Four hundred and two years ago this month, a group of courageous Pilgrims crossed the Atlantic on a ship seasoned from years of service in the English Channel. Their ship was the Mayflower. It bore a people with characteristics — bold, daring, foolish, devout — essential to the founding of a new nation that would become the envy of the world.

The year was 1620. Europe was two years into a thirty-year religious war that would raze its cities, starve its citizens, unleash plagues and take kings. They set their backs to the old ways — and bet their lives and their families on America.

What started in Plymouth changed the world — and changed it for the better. It was an audacious effort — a group of zealous religious men and women who put all their resources behind creating a new community in a new land, foreign to them in every way. They might as well have been the first explorers to step foot on Mars.

These characteristics are essential to understanding the American founding, and provide the basis for so much of what makes this nation great. The New York Times’s 1619 Project, and its award-winning and controversial creator, Nikole Hannah-Jones, were out with a book this time last year. It is not worth addressing, because it is self-refuting. When you assemble an entire project around the demonstrably false idea that preserving slavery was the primary motivation for the American Revolution, around the audacious claim that “our true founding is 1619, not 1776,” then retract or eliminate both claims while pretending they were never made, there is little more others can add… except to acknowledge what by now is plain for all to see: the purpose of the 1619 Project is not to teach history, but to propagandize.

The true American founding is in 1776, and there should be no historical dispute about it. The ideas assembled in that singular year were of such a unique combination and importance in human history, you must play contrarian games to insist otherwise. But I suggest to you the truth about 1620, amid a time of constant historical revisionism, is that it represents not just a convenient myth about the nation, but something that was essential to our founding.

We find that in the risk-taking character of the people who crossed the wine-dark sea of the Atlantic, mindful of all the courage it would take to navigate a new world filled with enormous potential for disease and death. We find it in their deeply held religious beliefs, rejecting church hierarchy and rules as contrary to Scripture, in favor of a world where you need not go through another to come before God and worship, and where they could raise their children in their own faith instead of losing them. And we find it in their sheer audacity — a group of a few more than 100, less than half of grown men, so committed to an idea and a belief in the rightness of their purpose that they would flout any pressure, any government, any restriction, even from the high monarch of England, James I.

The Mayflower Compact, written in anticipation of potential conflict and disunity upon their landing, made a nod to King James in its opening, and made clear that the group would bow only to “such a government and governors as we should by common consent agree to make and choose.”

It is a simple document to read today — simple, but powerful. It represents an assumption of equality under the law that would stretch from that moment into the future.

Along the way, the Pilgrims encountered one disaster after another. Before they turned west, they tried to head for Holland and were betrayed by the captain they hired. When the men escaped on a ship, their wives and children were imprisoned. They worked menial jobs while their plans fell through again and again before the journey began. And when they arrived, they came upon a land ravaged by plague and thrust into the onset of a harsh and unforgiving winter.

Before the spring, half of them would be dead.

But what the Pilgrims represented together was a community with the attributes willing to go on an “errand into the wilderness.” They believed, as Hebrews 11 told them, that they were “strangers and exiles on the earth… seeking a country of their own.” That was a country God would prepare for them — if they were bold enough to seek it.

These ideas did not just come from Europe. As the great Calvin Coolidge said 102 years ago, on the 300th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ arrival at Plymouth Rock:

They came not merely from the shores of the Old World. It will be in vain to search among recorded maps and history for their origin. They sailed up out of the infinite.

There was among them small trace of the vanities of life. They came undecked with orders of nobility. They were not children of fortune but of tribulation. Persecution, not preference, brought them hither; but it was a persecution in which they found a stern satisfaction. They cared little for titles; still less for the goods of this earth; but for an idea they would die. Measured by the standards of men of their time, they were the humble of the earth. Measured by later accomplishments, they were the mighty…

In appearance weak and persecuted they came rejected, despised, an insignificant band; in reality strong and independent, a mighty host of whom the world was not worthy, destined to free mankind. No captain ever led his forces to such a conquest. Oblivious to rank, yet men trace to them their lineage as to a royal house.

And those of us who love this country still do. My mother has a little wooden chair that has been passed down in her family for generations. It was taller once, a child’s high chair, but was cut down and used as a tool to help a child learn to walk. Its back is flat from the wear of little hands.

The likeliest owner was Jedediah Strong, born on May 7, 1637, in Plymouth, Massachusetts, to Abigail and John Strong, of Dorset and Somerset, who married after crossing the Atlantic. Jedediah, born under the governorship of William Bradford, would go on to marry Freedom Woodward, who bore a daughter they named Thankful, and began a line of Americans who would fight and serve through all our wars — French and Indian, Revolutionary, Civil, and on to Iraq and Afghanistan — all the way up until today.

Our nation and the creed it represents is under constant assault from the forces of revisionism, backed in a culture war by woke corporations, Big Tech and the most malevolent forces within our media, all seeking to deny our inheritance, destroy our past, forget the face of our fathers and demolish the value of the courage and dedication at the heart of America’s creation.

That’s why it’s incumbent upon us as Americans to renew this spirit in every generation — not to sit back on what prior generations built, but to strive out into the wilderness ourselves — the areas of life on this corner of God’s creation still undiscovered, contested, and unclaimed.

As the late great Richard John Neuhaus said it:

Why do we want everybody to work and everybody to participate? Because it is premised upon not just a vacuous notion of freedom, but a very deep respect for what John Paul II calls the subjectivity of society — the sheer magnificent diversity of human beings, when they are free, to imagine and to love and to associate. Tocqueville, when he came in the 1830s, saw in America the future of the world — not without some shadowed aspects, very deeply shadowed — but he saw a promise of a new way. And we, for better or for worse, and all undeserving on our part, represent that Tocquevillian possibility for the human project.

What a wondrous thing it is to see the world that, thanks to their courage and faith, the pilgrims made. For all its flaws, as humanity itself is flawed, it is a testament to their resolve and daring, without which the country and people we love so much would not exist. For this we can — and should — be thankful.

This is adapted from a monologue originally delivered on Fox News, which you can watch here: