I remember my first day at South Benfleet County Primary School with rare clarity. My mother left me at the school gate and I hadn’t been in the playground five minutes when a woman trotted up to me, suspended me in the air by my arm, and slapped my leg, hard. Apparently I ought to have stood still at the first blast of her whistle and lined up at the second. But no one had told me the drill. While everyone else stood stock-still, I had remained in motion. Her anger and unhesitating violence surprised, then shocked me. You might argue that I learned everything I needed to know about the world within five minutes of the start of my education. If you’re a publisher reading this, yes, I could probably squeeze a book out of it.

I quickly realized, however, that the playground supervisor was unrepresentative. My teacher Mrs. Asplin was loving and gentle, my fellow pupils friendly and cheerful. First prize for the weekly spelling test was to go and see the headmistress — a hideous, kindhearted old thing — and kiss her hairy cheek.

I went to South Benfleet Primary School between 1961 and 1968, always with the same set of classmates. I can confidently name perhaps forty out of forty-eight from the class photograph of 1966. We had one black girl (Evangeline McPherson), one fat boy (Raymond Phillips) and one pair of identical twins (Jill and Shen Sabri). Everyone had two parents, except Robert Gray, whose father died. The school was solidly lower middle-class and it seems to me that we were deliriously happy. In the class photograph everyone — including Robert Gray and the teacher, Mrs. Dobson — is laughing, really laughing.

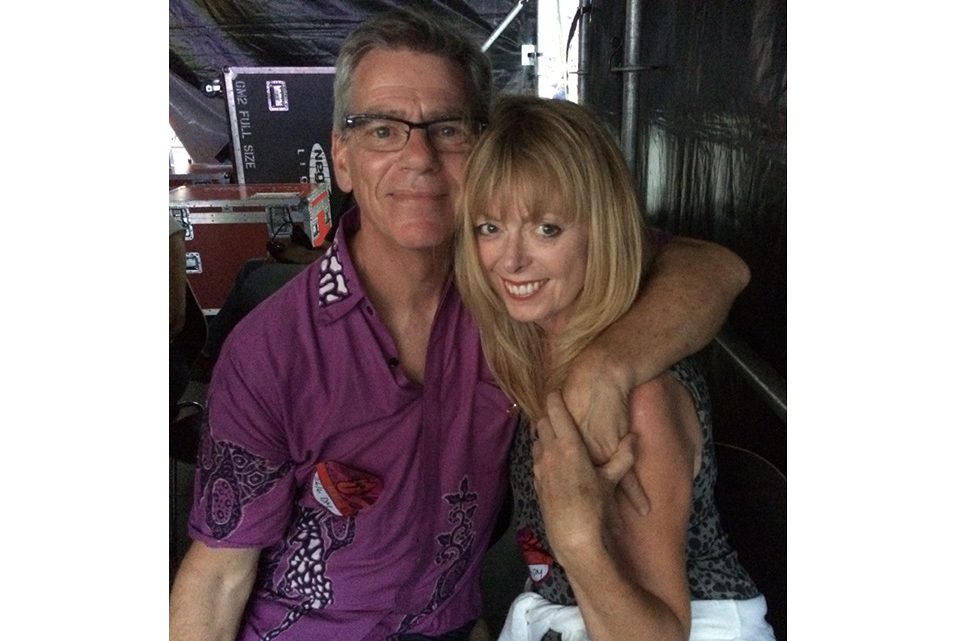

Of the forty-eight, I was best friends with Steven Heath and Simon Watson, known as Dot or Dotty. I used to go around to their houses and liked talking to their mums. It was extraordinary to me how friendly toward me and how funny were my friends’ parents. Steven’s mother June was a local light opera star and could sometimes be heard trilling and warbling in the lounge. She used to say to me, “Oh, you are a nit, Jel.”

When he grew up Dot worked as a gardener. Steven became a remedial teacher, then a humanistic funerary celebrant. They remained in Benfleet; I moved away. But we stayed in touch — with long gaps — throughout our lives. The last time I saw them was at a party a decade ago. Last week, in a weird sort of fait accompli, they turned up at my front door to say cheerio.

Dotty had texted out of the blue, naming a village close by. You live in the south of France, he said, right? Is it anywhere near this place by any chance? Because if it is, he and Steven would be staying there at the weekend and would like to take me out for dinner.

The south of France is enormous, I replied. The chances of hitting on the next village by a lucky chance is too remote. I don’t believe you, Dot. You’ve been googling — either me or Catriona.

Moreover, it’s too short notice, I said. I was in the worst week of the three-week chemotherapy cycle. Take me out to dinner? You’re having a laugh. My eating-out days are long gone.

Harsh, perhaps, but I didn’t want them to see me looking like this. If one last look was what they wanted, I couldn’t see the point of it. Far better to remember the person I was when we were five. Or twenty, when we all lived together in a sort of rock-band commune on a farm owned by East End gangster types. Besides, and to make matters worse, I had somehow poisoned myself on my own cooking and was exhausted by retching.

If you can’t speak frankly to those you’ve known since you were five, then who can you? They were obdurate, however. The worse my condition the greater the attraction — I’m certain of it. They flew to Nice, drove doggedly up into the hills in a hired car and first thing next morning texted a photograph of our village quartier with a caption asking for directions to the house.

“Bugger off,” I replied, phone in one hand, plastic bowl in the other. “I’m not telling you.”

“Don’t be like that, Jel,” replied Dotty.

Dot is a nice man. I relented. I talked them up the path to the house, then up the stairs, and received them lying in bed. Dot came over and laid a meaningful hand on my shoulder, as he used to playing Sticky Toffee or Off Ground Touch in the playground. Then he ran back out of the door, saying: “Found you! Your turn to come and look for us now!” I laughed. We laughed. Two old men come to visit a terminally ill third, all suddenly five again. Same personalities, same tics, same gait, same jockeying, same puerile sense of humor.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.