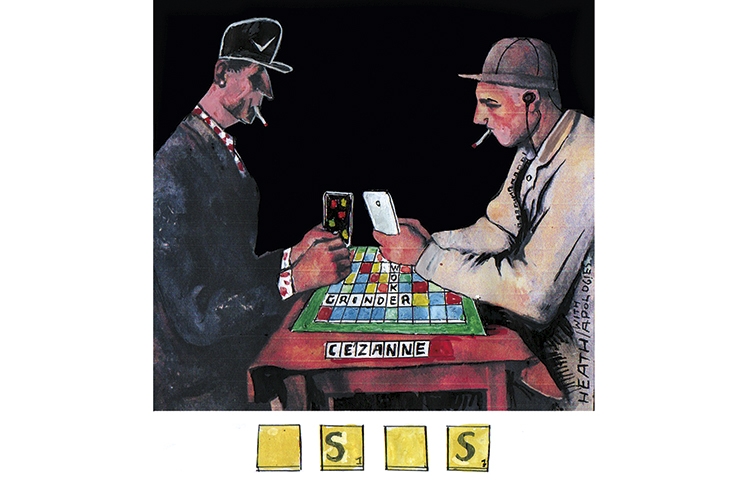

When the top players gathered in Torquay, England, last year for the World Scrabble Tournament (this year’s contest should have been this week, but has been cancelled thanks to you-know-what), it was to use ‘words’ like these in their games: dzo, ch, foyned, ghi…

Yep, that’s right; a whole lot of words that, let’s be frank about this, are not words. That’s why my spell-checker underlines them in red. The top players, you see, don’t win tournaments by being cleverer than the rest of us. They do it by memorizing a long list of non-words so they can avoid the problems ordinary players encounter.

With O I I I I U U on the rack, most of us would forfeit our turn while muttering something rude. But the top player finds a convenient H on the board in easy reach of a red triple-word square and plays hioi.

Raise an eyebrow at ybet and the top player raps the cover of their dictionary and declares that it’s a word. Ask what it means (archaic term for a medieval Mongolian heraldic symbol? Variant dialect spelling of an obsolete Albanian monetary unit?) and they come over all evasive. You see, it’s not a word anyone ever uses — except when playing Scrabble. It’s a special Scrabble word. A special ‘how to get out of a really tight spot while feeling awfully superior about it’ Scrabble non-word.

Top players aren’t interested in words for communication, just for maximizing their score. Indeed, believe it or not, some of the top players don’t speak very good English; they’re from Thailand or Malaysia and have memorized all these non-words with one goal in mind — winning tournaments.

It turns out that ybet is an archaic past participle of beat. At least that’s what the dictionaries say. But that’s the problem: these are special Scrabble dictionaries containing hundreds of obsolete junk words never attested in modern English but which top players find highly convenient when they’ve got a load of rubbish on their rack and want to dump it on the board.

And then they get indignant when you complain that the bizarre combination of letters for which they’ve just awarded themselves 70-odd points is not a real word. It’s like in Roald Dahl’s The Magic Finger when the duck asks Mr Gregg why humans shoot them:

‘“We are allowed to shoot ducks!”

“Who allows you?” asked the duck.

“We allow each other,” said Mr Gregg.’

No; if you want a level playing field the first thing to do is make sure you’re not playing against someone who sincerely believes that skriegh is a word just because it appears in a list some loser compiled so that losers can be winners.

I can’t emphasize this too strongly. As the old joke goes, when the cardiologist was asked how you can avoid having a heart attack, he said: ‘Choose your parents carefully.’ Same principle here: if you want to win at Scrabble, first make sure you’re playing the right person.

Now to the game itself. The main thing is to try to get your hands on both of the blank tiles and all four S tiles. Get them and the game’s as good as yours. There are various ways of securing these goodies but the only thing honest players can do is maximize their chances by playing the longest words possible so as to take more replacement tiles out of the bag. You can play a three-letter word for 20 points or a five-letter word for 17? Play the longer word — it’s worth sacrificing those three points to get two more chances to pull an S or a blank out of the bag.

And when playing Scrabble, although you take out letters and you put on words, you should think in syllables. Lots of words end in ing, ful, ive and ous, for example. A rack with N D I A E G R may not look so brilliant at first sight but once you spot the suffix ing you’ll soon see reading and a chance of bagging the 50 bonus points for playing all of your tiles.

Despite what the nerd dictionaries say, dich is not an English word. But yuk, thingy, shindig and nerd are. Lots of players think this game is about showing off posh vocab and forget all about slang and colloquialisms. A list of useful words for Scrabble contains zilch, phew, geez, schlep, confab…and loads more like that.

Which brings me to the important question of rude words. Playing a ‘word’ like zax is rude because it’s taking an unfair advantage. Playing everyday words which in conversation might be considered taboo is not rude; the game, after all, should be a celebration of our language’s rich and vibrant vocabulary.

[special_offer]

Some years ago I was playing my 97-year-old neighbor. (Remember what I said about choosing your opponent carefully?) Things were not going well; I was 40 points adrift in the endgame with just T H A S left on my rack. But when Marjorie, offloading letters and heading for the finish line as fast as she could, played hit, I saw my chance.

I didn’t worry about genteel proprieties. No; he who dares wins. I placed an S in front of her H, then played the letters H A T against the same S. The S was on a red square, so triple the score for both words and guess who ran out winner. Yay!

Marjorie nodded approvingly: she knew world-class play when she saw it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.