For a while now, we’ve been living through a renaissance of classical British cooking: a whole host of restaurants have been embracing the joy of the old school, the pies and puddings, the traditional and the retro. But there’s something missing. Bring back the savory!

An Edwardian favorite, a “savory” was an extra course that came towards the end of the meal, either just before or after pudding, or as an alternative to it. A savory should be small — a ‘morsel’ — and strongly flavored. To this end, the main ingredients are usually cheese, smoked or salted fish, bacon, or spice in the form of deviling. It is often served on toast or with a small pastry croute, and with something creamy as a foil. In the past hundred years, most savories have found new homes as starters or canapés, kitchen suppers or even breakfasts. But devils and angels on horseback, bone marrow on toast, deviled eggs, pâté on toast and Welsh rarebit were all originally served toward the end of a dinner, rather than the start.

There is something enlivening about a punchy, crunchy bite as the evening wanes

Welsh rarebit often graces the menu of the British dining institution St. John in London, and I went to a newly opened restaurant a couple of weeks ago that had cheese on toast on its pudding menu, sitting alongside a custard tart and a rhubarb ice cream. Maybe this is a sign of savory revival… dare I hope?

Ambrose Heath, who wrote a whole book on the topic — Good Savouries (1934) — describes savories as “the passion of the average Englishman and the bête noire of the ordinary housewife,” presumably because they are a pain in the arse to conjure up at the end of a long meal. A savory, he says, “often makes an admirable ending to a meal, like some unexpected witticism or a musing epigram at the close of a pleasant conversation.” He’s right: there is something enlivening about a punchy, crunchy bite as the evening wanes — although I’m less convinced by the popular idea that it aided digestion.

Scotch woodcock is a classic savory: strong salty anchovies, combined with soft, creamy eggs, all piled up on toast, and a silly name to boot. Actually, Heath omits Scotch woodcock from his savory compendium — although he does have two recipes for anchovy butter — but mentions in his introduction that he has left out the more popular, very obvious savories. So it is plausible that when he was writing in the 1930s, Scotch woodcock was so popular as to be de rigueur.

It is one of those dishes which is more of an idea than a recipe per se, and therefore variations abound. That idea is obviously a very simple one: toast, eggs, anchovies. There is one version (like mine below) which lays whole anchovies across the soft scrambled egg, while another omits whole anchovies, and instead spreads anchovy paste below the eggs. Other versions use a combination of whole anchovies and paste, and yet others involve a custard that goes on the anchovied bread, before it is grilled until leopard-spotted — a bit like an omelette Arnold Bennett.

You can make your own anchovy paste if you want (blitz butter, softened shallot and anchovies together until smooth), but most of the old-fashioned recipes simply call for Gentleman’s Relish. Gentleman’s Relish, or Patum Peperium, is a commercially produced anchovy paste that has been around since 1828. It is explicitly designed for spreading on toast and is intensely salty and strongly flavored; even the packaging cautions: “Use very sparingly!” We always have a pot of the stuff in our fridge (it keeps forever), and it is extremely useful when you need to satisfy a salty craving, but when it comes to Scotch woodcock, I plump for whole anchovies.

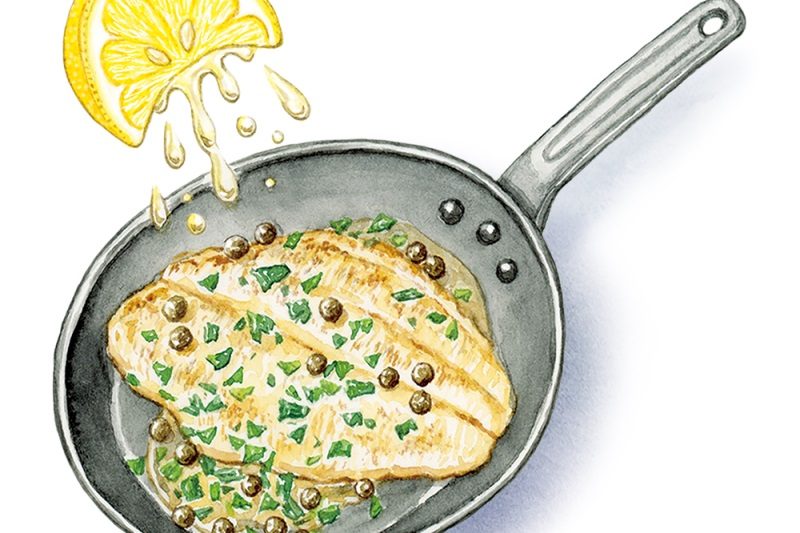

My recipe keeps it relatively simple: the eggs are soft and buttery, cooked slowly and without cream or milk. They should form wavelike curds as they cook, but they are definitely scrambled eggs rather than custard. Toast should be thin, crisp, crusts removed and buttered. And then on top of the eggs, following Arabella Boxer in her 1991 Book of British Food, I crisscross anchovies and lay a single caper in between each angle.

Takes 5 mins

Cooks 5 mins

Serves two as a meal / four as a savoury

- 4 eggs

- a large knob of butter (plus extra for buttering toast)

- 4 slices white bread

- 8 anchovies

- 1 tbsp capers, drained

- Toast the bread, butter it, remove the crusts and cut each slice into quarters for savories or diagonally in half for breakfast or supper

- Beat the eggs in a jug or bowl and season with salt and pepper. Melt the butter in a nonstick pan over gentle heat and, when it starts to foam, pour in the eggs. Don’t fiddle with them too much, lifting and gently stirring them just as they start to set, so you end up with waves of egg, rather than little bits. As soon as they are starting to set but still soft, spoon them on to the prepared toast

- Crisscross two anchovies over the eggs, placing a caper in each of the quadrants. Serve immediately

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.