Regrets, I’ve had a few, but unlike Mr. “My Way,” mine are enough to mention. (Didn’t Hoboken Frank at least regret slapping Ava Gardner or hanging out with Joey Bishop?)

“When you see the end of things coming close and staring at you,” as Jason Robards tells his son in Ray Bradbury’s filmic adaptation of his own novel, Something Wicked This Way Comes, “it’s not what you’ve done that you regret — it’s what you didn’t do.” (For good or ill, cataracts prevent me from seeing the coming end.)

Surely some missed opportunities are worth missing. For instance, I doubt if any of the awestruck Lou Reed fans whom the rock’n’roll coprophage famously invited to defecate into his mouth regretted turning down the chance.

Like most seeming extroverts, I have always thought myself on the shy side. So my regrets are for things undone, unmade, untold. They’re hardly earth-shattering, but still…

Turning a corner in Buffalo’s Albright-Knox Art Gallery I came upon a man in a white suit, his face dominated by white eyeglasses that looked like yogurt pretzels. It was Tom Wolfe, taking in an exhibit dedicated to James Tissot, the nineteenth-century French painter of upper-class English women. Wolfe, guided by a young docent, was not exactly aiming at inconspicuousness in that Good Humor Ice Cream man get-up.

I was with Peter Dzwonkoski, director of Rare Books and Special Collections at the University of Rochester — and a rare-book dealer himself. We looked at each other. Should we? “Mr. Wolfe, I don’t wanna bother you but just wanted to say I love your books: Bonfire of the Vanities, The Right Stuff, the one about Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters.”

Nah, we left him alone.

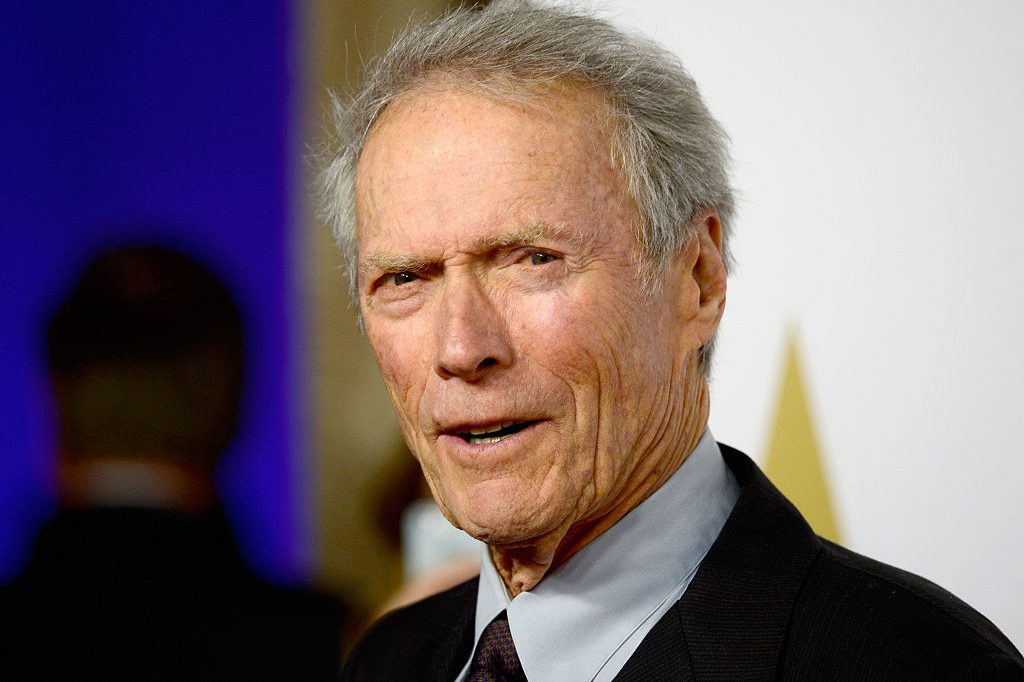

During a break in the recording of the score of a movie I’d scripted, I left the Eastwood Scoring Stage at Warner Brothers and strolled down a little avenue of bungalow offices. I was a long putt away from an elderly man slowly removing himself from a car, limb by aching limb. “Who’s that fossil?” I wondered. ’Twas Clint Eastwood himself, whom I had seen pummeling a punk kid a week or so earlier on the big screen in Trouble with the Curve!

“Mr. Eastwood,” I imagined myself saying, “I think The Outlaw Josey Wales is a masterpiece.” But I walked on by, in silence. Later I told the great sound engineer Stanley Tajima Johnston of this close encounter. He said that Clint is unfailingly gracious, and I should have approached him. Ah, well. (Stanley, the long-time recording engineer for Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, was gracious, too. When I told him that Neil Young was the only one of that quartet I could stand, he gently informed me that he worked mostly with Graham Nash and that ole Neil was the most difficult member of the group.)

I spent a morning interviewing Shelby Foote, novelist and author of the monumental three-volume The Civil War: A Narrative, at his Memphis home. Foote greeted me at the door wearing threadbare pajamas, his long hair uncombed, and drawled, “Ah wuz jes’ goin’ to the whiskey stoah.” He was an absolute delight, soulful and erudite and witty, and after chatting for two hours I almost took a first-edition of The Civil War: Volume One out of my satchel and asked him to sign it. But I had read that Foote hated signing, and I didn’t want to spoil the moment. Another unrealized bequest to my descendants.

I was sitting at the end of the bench during a JV baseball game, talking about girls with my friend Kenny. It was the bottom of the last, score tied, man on third. The coach, who had a volatile gene, barked, “Kauffman!” I jumped to attention. He grabbed me by the jersey. “Can you guarantee me a successful suicide squeeze?” (Laying down a bunt was one of my few undisputed talents.)

“Well, there are no guarantees in life,” I replied, smart-alecky. He pushed me back toward the bench. The batter struck out. It’s funny, the things we remember.

Maybe Wolfe and Clint would have blown me off. Foote might have given me the boot. I probably would have lunged at and missed bunting the inevitable out-of-the-strike-zone pitch, leaving the runner from third dead at home.

But I guess I’ll never know.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply