Disney’s latest remake of The Little Mermaid, out last week, has, it seems, a message for the British royal family. When the prince wants to know the name of the mermaid, played by Halle Bailey, he tries to guess. “Diana?” Nope. “Catherine?” She pulls a face. Cue royal watchers identifying a snub of Kate, the Princess of Wales.

Disney’s 1990 take on The Little Mermaid wasn’t quite the story that Hans Christian Andersen wrote — not having much to say about the mermaid’s quest for an immortal soul — but it did find one fan. As Meghan Markle observed in her interview with Oprah Winfrey: “Who as an adult really watches The Little Mermaid? But it came on… and I went “Oh my God, she falls in love with the prince and because of that loses her voice.’” If only.

Let’s abandon the spurious parallels between the royals and mermaids then and observe that when it comes to the early version of this girl-fish hybrid, it’s actually quite difficult to distinguish mermaids from sirens, those creatures that enchant gullible young men with their sex appeal before dragging them underwater to drown. In one medieval bestiary at the British Library, a thirteenth-century French manuscript shows what looks like a mermaid but is labeled a siren, pulling one unfortunate oarsman by the hair into the sea. Nearby a male centaur gallops off, a reminder that the human-animal hybrid takes several forms.

Early mermaids are often depicted holding a comb or looking glass, suggesting vanity, like the splendid creature in the Luttrell Psalter. In a Bestiaire d’Amour at the Morgan Library, the mermaid has two tails, more like fishy legs. Which, funnily enough, is how the original merman, Poseidon’s son Triton, is sometimes shown. During the Greco-Roman period, “triton” came to refer to all mermen, often depicted using conch shells as musical horns.

There are all sorts of mythical representations of mermaids, including Celtic ones, but they leapt from legend to history when Christopher Columbus soberly recorded in his logbook having seen three off the coast of Africa raising themselves above the water. He observed disappointedly that they were not at all pretty, having faces like men.

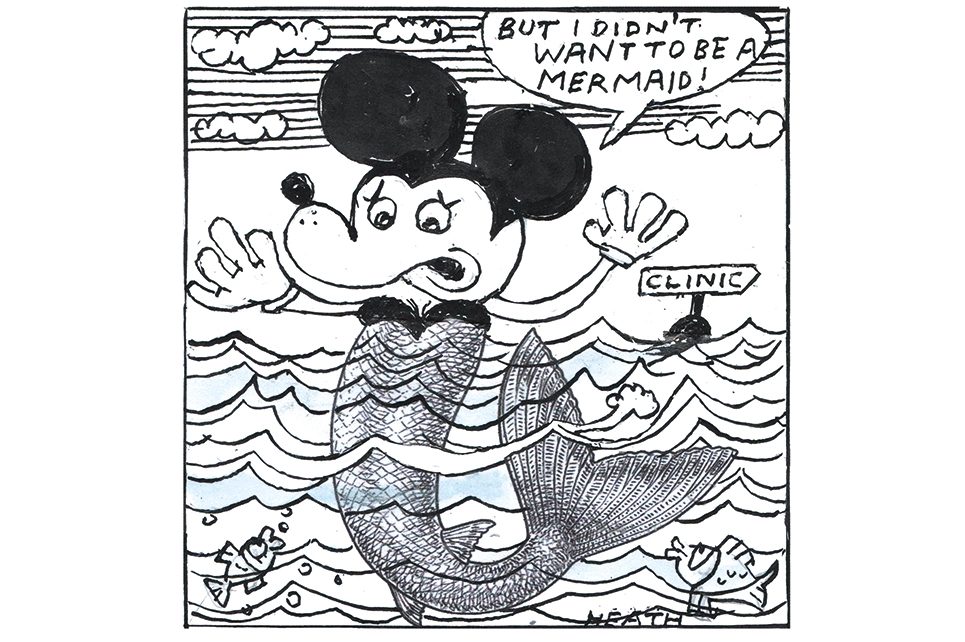

The real transmogrification of the mermaid came in our own time. Search the term on the internet and you’ll find a controversial British charity that supports gender variant and transgender youth. It has been accused of, among other things, sending breast binders to adolescents without parents’ consent.

Mermaids even have their own Netflix documentary, MerPeople, where we find that dressing up as quasi-fish is a multi-million dollar thing in the US. We are shown mer-beauty pageants and a whole business based on people in sparkly bikini tops and iridescent tails. The trailer concludes: “Anybody can be a mermaid; you just have to believe.” Actually, in Hans Christian Andersen’s tale (spoiler alert), the Little Mermaid concludes her story by joining the Daughters of the Air, who roam the world doing good deeds. And she does gain a human soul.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.