Without divulging my exact age, I will tell you my generational status lies tucked in the crevasse between solid Gen X and millennial. In other words, I’m old enough to remember having a landline telephone and waiting for dial-up internet. I grew up during the slow march toward the homogeneity of interconnectedness. Cable news cleansed us of striking regional accents and nomenclature. At the same time, microwave meals and fast-food drive-throughs became staples for two-parent working families and busy schedules.

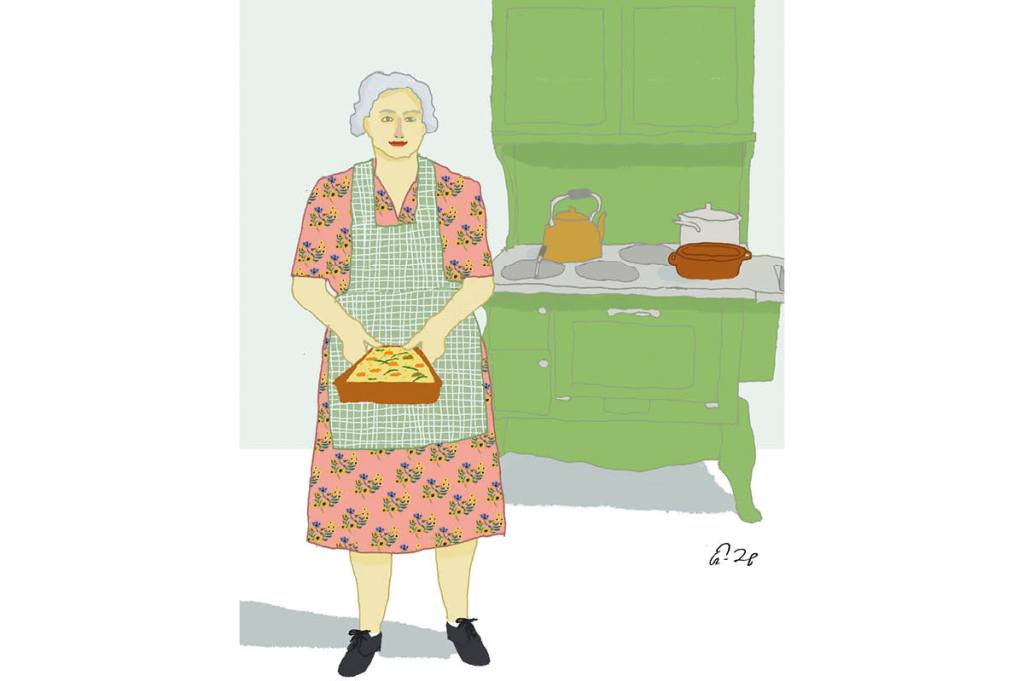

I’m a born and bred Minnesotan, from a state settled and populated with an abundance of Norwegians, Swedes and Germans and a spattering of Finns, Poles and Russians who recognized their homeland in the frigid winter tundra and bountiful farmland. Their hearty culinary traditions prevailed just as the homesteaders did. Up to a few decades ago, before organized religion took a real hit and people found community in other spheres, the local Lutheran church basement was where families and friends congregated to share kinship, coffee, sweet baked goods and savory bites. And as renowned as the silver-haired grandmothers who ran the church’s Women’s Auxiliary were the massive amounts of strange yet delectable delicacies they produced for expectant crowds.

Lefse was generally reserved for special occasions. The thin, potato-based Norwegian flatbread is cooked fresh on a circular griddle, spread with butter, sprinkled with white sugar or lingonberry jam, and rolled before being consumed by white-bearded, growly husbands and sticky-fingered children. There’s also the notoriously foul-smelling and gelatinous lutefisk, made with salted and dried cod that has been cured in lye and rehydrated, then cooked and served with cream sauce and potatoes — truly a food of the Old World and not for the faint of heart or those with sensitive olfactory receptors. Some even credit the dish with insulating certain pockets of immigrants from outsiders because it was so strange and offensive-smelling.

It isn’t surprising that such labor-intensive, specialized dishes fell out of favor in today’s era of DoorDash convenience. But what of the easier home cooking that doesn’t require special tools, ingredients or culinary skills? Of course, it is the humble Midwest Hotdish to which I refer, that slab of warm, baked goodness filled with meat and vegetables, bound with canned creamed soup and topped with a generous layer of tots.

You might be thinking, “That’s just a casserole!” But you dare not say it out loud unless you wish to suffer the wrath of any lady of a certain age with ready access to a sturdy wooden spoon to swat your backside. In fact, the church cookbook passed down to me by my mother has a whole chapter devoted to Hotdish: it has everything from the simple Cheese Hotdish (the name basically says it all) to the slightly more sophisticated That Hotdish (the addition of carrots and celery offers a nice textural variation) and the more adventurous Southwest Hotdish with one green sweet pepper and a half cup of mild salsa, with mild printed in italics, the only emphasized word in the whole Hotdish chapter (the natives consider ketchup spicy, so this recipe could ruffle a few feathers) is included. The variations are endless — just don’t call them casseroles.

What is the difference? Attitude, really. Every American region manifests its character through food. The long, cold, dark winters of the upper Midwest shaped generations of hardened and humble men and women; the climate lends itself to the warm, self-effacing simplicity of hotdish.

As the nation becomes more interconnected, regional differences lose their particular flair and passion. Younger people don’t seem interested in carrying on traditions that might detract from their suave online personae. But let’s face it, a droolworthy picture of the dish from a posh Michelin-starred restaurant isn’t really as appealing as the heaping plate of creamy ground beef and tots from your grandma’s lace-curtained kitchen. Young people are more disconnected from grandparents and older relatives who have access to these recipes and want to share them and the love behind the traditions. Plus, it’s much easier to grab that box of Betty Crocker cake mix to whip up a “homemade” cake than to dig through Memaw’s recipe box and decipher her broken cursive script and attempt her Hummingbird cake or pecan pie.

Mark Twain understood the beauty in enjoying the simplest meal sans the intrusion that now so often interferes with savoring our own experiences — something that cannot be conveyed in a tweet or Instagram reel. “I know the look of an apple that is roasting and sizzling on the hearth on a winter’s evening, and I know the comfort that comes of eating it hot, along with some sugar and a drench of cream… I know how the nuts taken in conjunction with winter apples, cider and donuts make old people’s tales and old jokes sound fresh and crisp and enchanting.”

A few years ago, I was given a treasure of an anthropological text cleverly disguised as a cookbook. Ernest Matthew Mickler’s White Trash Cooking, published in 1986, is a revealing peek into an overlooked time and way of life. The book is a walk through humble Southern living: creaky porch swings occupied by ladies in homemade dresses sipping sweet tea and old men with easy smiles and calloused hands. In his introduction, Mickler refrains from defining White Trash, “because,” he writes, “for us, as for our southern White Trash cooking, there are no hard and fast rules… the first thing you’ve got to understand is that there’s white trash and there’s White Trash. Manners and pride separate the two.” The sentiment echoes the ethos of traditional cooking in every region of America. And Mickler’s list of recipes promise to fill one’s soul just as full as one’s stomach.

Betty Sue’s Fried Okra, Mock Cooter Stew and Mama Leila’s Hand-Me-Down Oven-Baked Possum are a sampling of dishes unique to the Southern culinary tradition. I asked a young millennial acquaintance from Mississippi if she was familiar with any of these delicacies. “I’ve never seen a possum, and I’m afraid to ask what a cooter is,” was her response. (Her expression and furrowed brow indicated an even mix of relief and puzzlement when I told her it was a medium-sized freshwater turtle.)

Learning at grandma’s hip how much cream (never low-fat milk!) to add for a perfect New England Clam Chowder or the precise time to flip a Swedish pancake to get that extra crunch on the outside is an entirely different experience from following a TikTok culinary influencer who looks like she’s barely old enough to sample the sherry called for in your great-aunt’s closely guarded wild rice soup recipe.

The foreword to my well-worn Lutheran Church Ladies’ cookbook illustrates what we lose when these traditions and foods are forgotten: the very history of our nation and the disparate communities that made it culturally bountiful and endearing. “These recipes are intended to reflect our history, so they include rich and delicious dishes from our parents and grandparents. It is our sincere hope that you will find this book an accurate source of kitchen inspiration for good food and good fun. Much pride and many good memories of family and friends are attached to each recipe.”

Now, if I may be excused, I have a sudden hankering for lutefisk.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2023 World edition.