The tailor’s art is a triumph of mind over schmatte. Not just in the physical cutting and stitching, but in the faith that style makes content. This, not the question of which way you dress, is the secret compact between tailor and client. ‘Every faculty of his soul, spirit, purse and person is heroically consecrated to this one object, the wearing of clothes wisely and well, so that as others dress to live, he lives to dress,’ Carlyle wrote of the dandy in Sartor Resartus.

Tommy Nutter was one of Tommy Carlyle’s dandies, a ‘clothes-wearing man’ and a ‘poet of the cloth’. From 1969 to 1976, Nutter bestrode the world of tailoring like a Narcissus. Though he could barely manage a backstitch, his designs rewrote the book on male style. Any good English suit carries a whisper of Nutter in the cut of its cloth. Never mind the quality, feel the width of Lance Richardson’s vivid and tragic The House of Nutter.

Born in 1943, Nutter grew up dreaming of Hollywood. At 16 he became a tea boy at the Ministry of Works. Driven ‘practically insane with boredom’, this camp Kipps escaped to the dusty Edwardian dreamworld of Ward & Co., 35 Savile Row: impeccable stitching, fashion-proofed design, declining revenues. Nutter took evening classes in tailoring and worked his way up to the shop floor. Tall, handsome and promiscuous, he mingled after work with ‘top-drawer queers’ such as Francis Bacon at the Rockingham Club in Soho, which Quentin Crisp called ‘the closet of closets’. By 1967, this ‘comely youth from Edgware’ had befriended Brian Epstein’s assistant, Peter Brown.

On Valentine’s Day 1969, Nutter opened the Row’s first new shop in a century. His investors were Brown, a clerk at the House of Lords named James Vallance White, the caterwauling Cilla Black, and the Scouse Svengali, Black’s husband-manager Bobby Willis. The Beatles connection, Vallance White admits, was ‘not uninfluential’ in their thinking. Later that year, three-quarters of the Beatles wore Nutters for the cover of Abbey Road. Nutters sold more than 1,000 suits in its first year. The clientele included Peter Sellers, Kenneth Tynan, David Hockney, Mick Jagger and Prince Rajsinh of Rajpipla. Bianca Jagger came too, but Nutter discouraged female customers by charging them extra. ‘I don’t know how to deal with women’s tits,’ he admitted.

You didn’t have to be mad to work at Nutters, but it helped. Huntsman had Royal Warrants in their window. Poole had souvenirs from the Great Exhibition. Nutters had ‘a painted mural of Egyptian ruins’, a ‘Punch and Judy puppet show’, a ‘riot of royal purple and fuchsia-coloured ostrich feathers’, and empty champagne bottles, with full ones inside for the customers. Nutter wanted to ‘show what we do, so people will not be frightened to come in’. He was not democratising the Row — he had risen the traditional way and he maintained bespoke standards — but saving it, by reconciling aristocratic Edwardian style with the demotic peacocking of Swinging London.

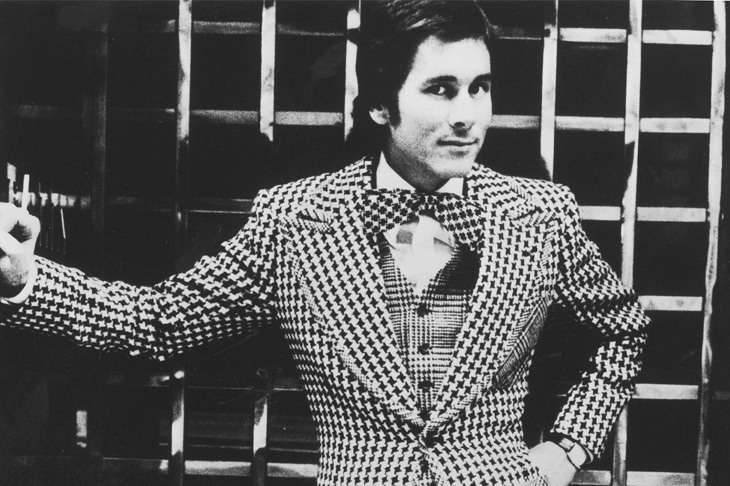

The Nutter cutter, Edward Sexton, had specialised in building hacking jackets. The Nutter silhouette redrew that Victorian template. Nutter emphasised the horizontal line of the shoulder, and emphasised it twice more by straightening the coat pockets and extending the drape to almost Teddy Boy-ish length. He added ‘shape and flair’ to the skirt, tightened the waist and chest, and replaced the usual single-breasted lapel with giant double-breasted ones that grazed the sleeve heads. Sexton cut the ticket and waistcoat pockets ‘seriously deep’; handy for stashing dope and pills. Nutter, echoing Dior’s reinvention of female fashion in 1947, called this the ‘New Look’ for men. Hardy Amies thought it ‘marvellous’, and Nutter ‘the most exciting tailor on Savile Row in decades’. Punch called it ‘an eccentric mix of Lord Emsworth, The Great Gatsby and Bozo the Clown’.

It was a butterfly look, and fashion has a dragonfly’s lifespan. Denim was coming in, and Nutter, Edward Sexton recalls, was a ‘fucking useless’ businessman. In 1976, Nutter sold his shares to Sexton. Nutter planned to take over America, but became a salesman for Kilgour, French & Stanbury. In 1979, he launched an off-the-peg collection for Austin Reed. In his later photographs, he resembles John Inman in Are You Being Served? In 1992, he died painfully of Aids. By the end, he was unable to recognise his visitors. He thought Cilla Black was Barbara Windsor. It was a small mercy.