As many of us who grew up in America in the 1960s and 1970s learned, MAD magazine didn’t, as our parents warned us, warp our brains — because our brains were pretty warped to begin with. It was a time when what passed for culture was almost entirely scripted by Madison Avenue, promising that overpriced concoctions of sugar water and aspirin would eliminate all pain, social awkwardness and anxiety, or transport us to happy, sex-crazed beach parties with packs of photogenic young people.

Our movies and television shows depicted America as the hero and ultimate victor of every war and conflagration on urban or foreign battlefields or even in outer space; and the people who ran our federal institutions unquestionably knew exactly what they were doing all the time — unlike the “usual gang of idiots” at MAD. The problem for many of us was that those self-professed idiots made more sense than the authority figures. That was because MAD didn’t just make us laugh, often to the point of tears; it freed us from the stupidest, most unsustainable beliefs we were supposed to hold about our country — such as, well, that it wasn’t run by idiots.

MAD’s best-known contributors shared one vision: that America wasn’t at all what America said it was

Nothing measures the cultural shift regarding MAD better than the publication of this collection of reminiscences by its longtime admirers and contributors. The magazine our parents were once afraid — or ashamed — to buy us in drug stores and supermarkets (“No, hon, you can’t have that!”) is now being praised in a book published by the Library of America. They usually produce doorstop compilations of Henry James, Zora Neale Hurston and Ernest Hemingway — the sort of fiercely lionized American writers who, along with their scholarly admirers, wouldn’t have been caught dead in a queue buying MAD magazine. Imagine Henry James snorting root beer through his nose while reading one of Al Jaffee’s “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions?” (Optometrist to young woman: “Would you like your eyes examined?” Young woman: “No, I’d like a pound of chopped liver. I get my eyes examined in a delicatessen!”) You cannot — and if there’s one person who could have used a good nasal explosion of root beer while reading Al Jaffee it was definitely Henry James.

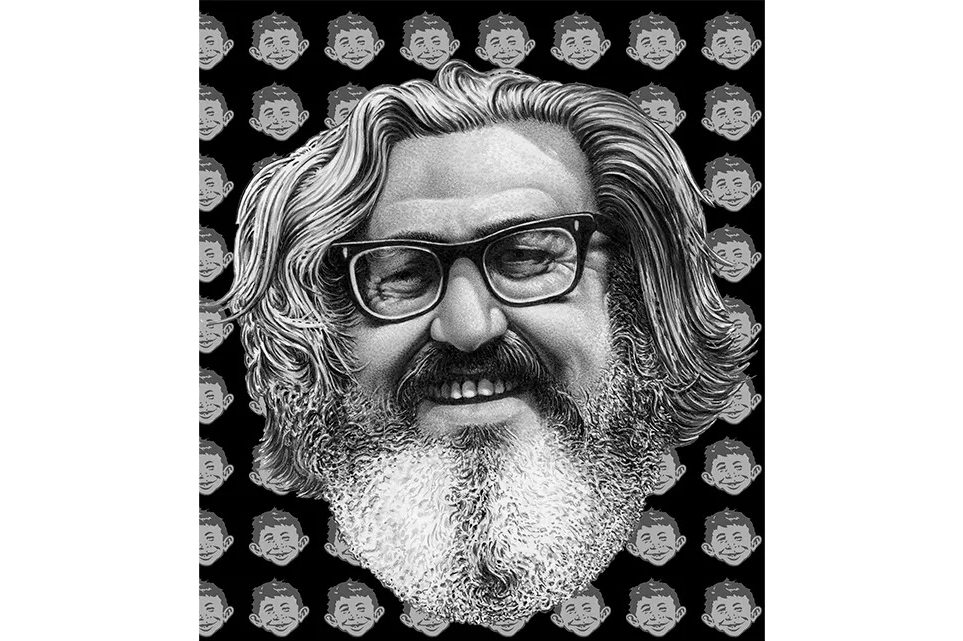

Founded by Harvey Kurtzman, the editor, and William Gaines, the publisher, MAD magazine started as a comic book and soon advanced to magazine format to avoid the censors. But after many of its contributors left to join a competitor, MAD became an anarchic assembly of young Jewish artists and writers who were given what they needed by the new editor, Al Feldstein — in other words, lots of messy space to run around in anarchically.

It’s hard to define anything resembling a MAD “style.” Its best known contributors only shared one vision of the world: that America wasn’t at all what America said it was. Upright citizens were actually blobby-nosed pudges who belched, farted and splatted their way through Don Martin cartoons. The Cold War was a recurring game of mutually assured destruction, committed by pointy-nosed, interchangeable hero-villains in “Spy vs Spy,” a strip drawn by Antonio Prohías, a refugee from Castro’s Cuba. And when it came to Hollywood nonsense, MAD’s greatest geniuses may well have been the expression-perfect Mort Drucker and the tone-perfect Dick DeBartolo. As Grady Hendrix recounts in his contribution, “Cahiers du CinéMAD.”

We thrilled to Francis Ford Coppola’s ‘The Oddfather:’ Arthur Penn’s revisionist western ‘Little Dull Man:’ the sophisticated sex comedy ‘Shampooped:’ and Stanley Kubrick’s groundbreaking ‘201 Min. of a Space Idiocy.’ For us, Casablanca was cast with professional wrestlers, My Fair Lady featured women’s libbers trying to reform a male chauvinist Burt Reynolds, and The Exorcist ended with Satan demanding a six-film deal.

When it came to America’s primary cultural export, MAD’s contributors never forgot for a moment that Hollywood was always about the money.

Reading The MAD Files is nowhere near as much fun as reading MAD itself — and, surprisingly, it contains no reprints from the magazine. Some of best pieces are reminiscences by formerly young readers who have grown into sensibly appreciative adults; two essays about the often forgotten women who wrote and drew MAD; and several (including ones by Nathan Abrams and Liel Leibovitz) that examine the overwhelmingly Jewish nature — sometimes recalcitrant, sometimes devout — of its editors and contributors.

In general, the book contributes to the gathering historical record of a magazine that would never take such a record seriously. Jonathan Lethem and Mark Allen have even contributed a pastiche of Al Jaffee’s back-page “fold-in.” MAD’s answer to the fold-outs in Playboy. There are also enjoyable contributions by Art Spiegelman, the New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast and Geoffrey O’Brien. At the same time, other affectionate essays, such as one by Adam Gopnik that quotes Jonathan Swift and George Santayana, go to extremes. For, despite all its strengths, this book takes MAD more seriously than MAD’s contributors ever took themselves.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.