It was perhaps a mistake to re-read Sebastian Barry’s award-winning Days Without End before its sequel, A Thousand Moons, since the two soon began to swim together in my head — not least because Moons is a kind of mirror image of Days. Winona, the Indian orphan girl adopted by the Union soldiers Thomas McNulty and ‘handsome’ John Cole in Days, takes over the narration. We’re now post-civil war, and the three are scraping a living on a farm in Tennessee.

Days (with Thomas as narrator) began with two starving émigré boys earning their keep as ‘prairie fairies’ in a Missouri saloon before joining the army. Moons opens with Winona in her teens. She’s a ‘child of nothing’, her status as an Indian even lower than that of the newly freed black slaves. Hers is both a coming-of-age and a survival story.

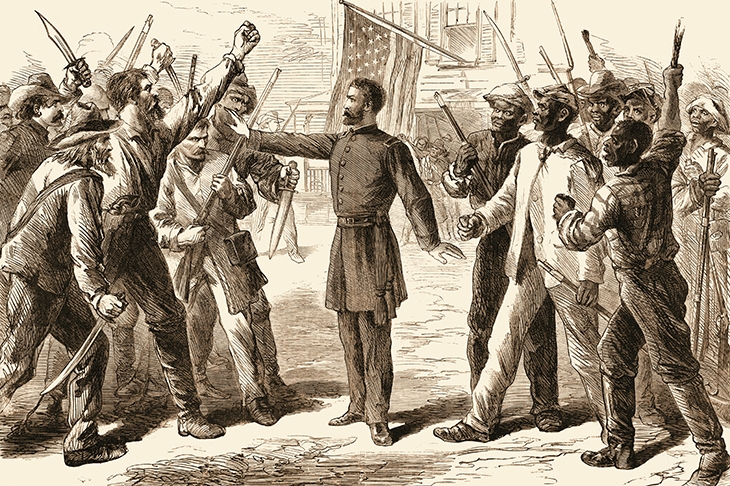

The key incidents are her rape by a white boy and the beating of Tennyson Bouguereau, a former slave. Much of the fascination of the novel derives from its post-war setting — a time when thousands of men are disgruntled by the ‘air of peace’ that chokes them. Farmers have lost their slave labor, resentment of the freed blacks is bitter, and night riders and rebels are everywhere. Law is ‘barely possible’.

The mirror-imaging between Days and Moons is also evident in the cross-dressing. In Days, it’s Thomas who’s in and out of dresses and army uniform; in Moons, it’s Winona who, in her attempt to defend herself and make amends to Tennyson, adopts boy’s clothes and finds love with an Indian girl, Peg of the yellow dress. In Days, Thomas nearly ends on the gallows; in Moons, well, I won’t tell…except that now and again I felt as though I were in As You Like It as a western.

But forget the plot: it’s the writing that puts Barry on the side of the angels. It is vivid, lyrical and awash with metaphors and quasi-biblical proverbs — ‘a human finds a little medicine in another’s sadness’. The inner lives of the characters shine with a timeless quality. Which brings me to the title. The thousand moons refers to Winona’s mother’s (and therefore the Lakota tribe’s) concept of time, which is a kind of continuity. If you keep walking long enough, you’ll meet your ancestors.

Halfway through this novel I was so much under Barry’s spell I wanted to read everything he’d ever written. By the end? Why did I feel slightly over-charmed? And is there a word for that? Goddammit, Sebastian Barry will know it.

This article was originally published in

The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.