Most directors don’t voluntarily retire. If you’re lucky enough to make movies at a studio level for decades, you’re not going to stop unless you can’t remember the name of the president or what year it is. Plastic enhancements may have extended the shelf life of actors and musicians, but directors can keep working until they’re on oxygen (John Huston), half-blind (John Ford), blind (Akira Kurosawa) or cancer ridden, manic, and defecating in buckets (Michael Curtiz).

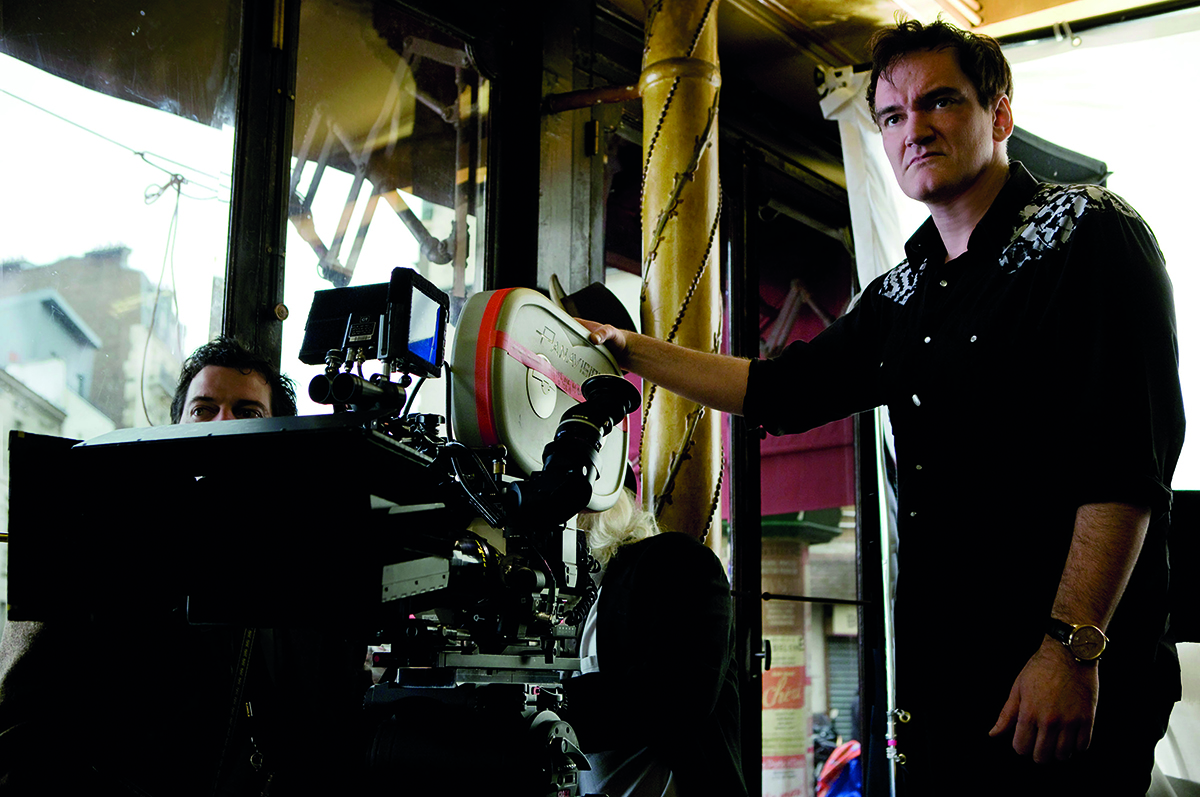

For over a decade, Quentin Tarantino has said that he’ll retire after ten movies — or when he hits sixty, the age he insists all filmmakers begin their steep decline. With his tenth and final film The Movie Critic in pre-production, and having turned sixty just a few months ago, Tarantino is sticking to the plan he outlined years ago.

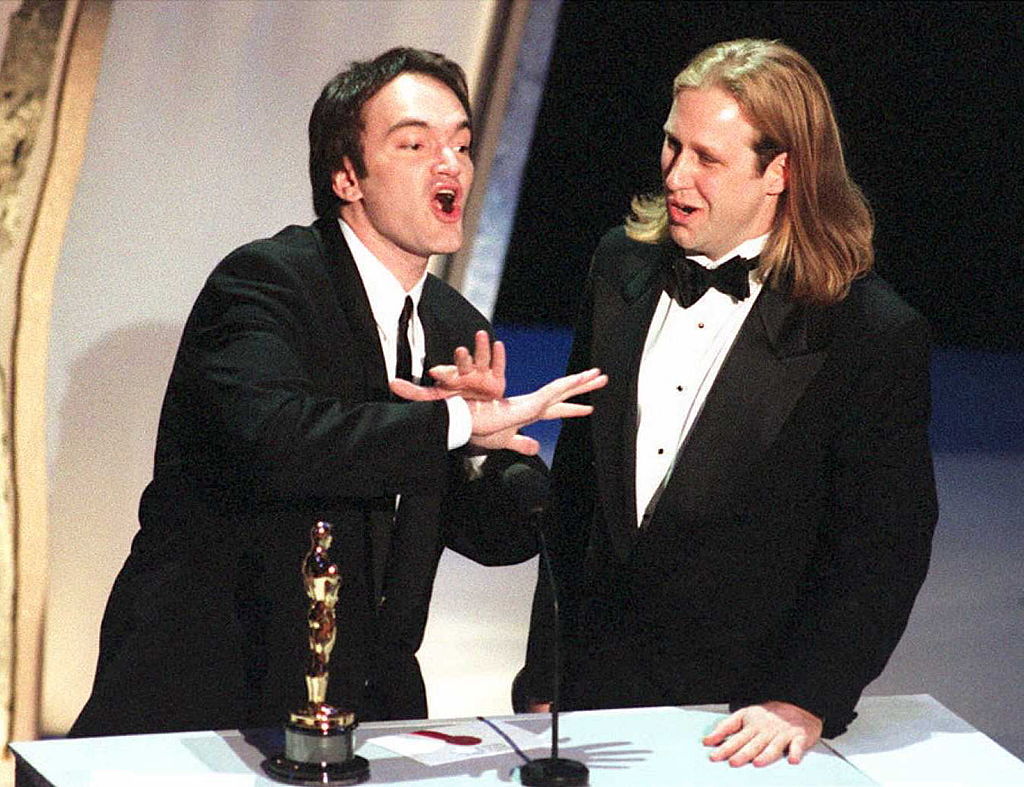

No one believed him. But in the last two years, Tarantino has begun the transition. He has published two books — a novelization of Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood and Cinema Speculation, a nonfiction analysis and movie memoir — and started a podcast with former co-worker and Pulp Fiction co-writer Roger Avary and Roger’s daughter, Gala Avary. On The Video Archives Podcast, the trio talk about tapes sourced from the actual Video Archives collection, the video store where Tarantino and Avery worked for most of the Eighties. (By the time the store closed in 1995, Tarantino and Avary were wealthy enough to buy the entire inventory, shelves and all).

The podcast boom of the last decade has produced plenty of junk, and it isn’t fun looking for diamonds in the rough, rough, rough alleys of Spotify, YouTube and SoundCloud. The critics I’d gladly listen to — Jonathan Rosenbaum, Janet Maslin, Armond White — are few and far between. Tarantino is a different story: when he has a question about 1976’s Mikey and Nicky, he can email writer/director Elaine May and read her prompt response. During a discussion on Peter Hyams’s 1974 feature debut Busting, the duo marvel at all of the “doorway dolly” shots in the movie, going on to explain for the layperson what a doorway dolly is, and how Hyams’s fluid camerawork presages his move to cinematographer a decade later.

A segment on Joe Dante’s excellent 1978 Jaws rip-off Piranha doesn’t consist of a bunch of stoned idiots going gaga over the primitive but impressive special effects or complaining about the “bad acting.” Instead it’s a closely argued case for the first piranha attack as an editing feat on the level of Sergei Eisenstein. A bit bananas? Tarantino backs it up: not only does he know Joe Dante (a guest on the show), he knows how New World Pictures and their directors worked in the 1970s and early 1980s.

Gala Avary comes on after Tarantino and her father to join in the discussion and provide information on specific home video releases, who put them out, where to find them and streaming options. As host, she makes the show, saving it from becoming an uninterrupted pissing contest between friends. They sing the praises of “heavy tapes” with good image quality and savage wildly inaccurate synopses on the backs of certain boxes.

Besides having the warmth of a family affair, The Video Archives Podcast is yet another unexpected, self-effacing and passionate gesture by Tarantino. He could be doing anything he wants, and he’s spent the last two years reading bad box art copy and waxing on “revenge-matics” like Lipstick, The One-Armed Executioner, Buster and Billie and his beloved Rolling Thunder, the 1977 John Flynn film that, according to screenwriter Paul Schrader, features in The Movie Critic. It’s also worth noting that Tarantino and Avary have been reading “old reviews” by fictional critics named Jim Sheldon and Franklin Brauner — perhaps Tarantino’s final film is being developed and teased right in front of us.

Martin Scorsese ruefully told Deadline in May that “I’m old. I want to tell stories, but there’s no more time.” He’s eighty, and Scorsese’s massive productions usually take between two and three years from conception to completion — unlike his on-off collaborator Schrader, who said recently that Scorsese, along with Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, like “the big toys”: cranes, massive sets, hundreds of extras. Schrader can make films like First Reformed for $5 million and under. Jean-Luc Godard, who died last year at ninety-one, just had a twenty-minute “trailer for a film that will never exist” premiere at Cannes.

Phony Wars is made up of pencil sketches, photographs, collages, voiceover, music and sound effects. Not all masters need the big toys. And not all masters need to keep making movies. For some, paper, pencils and Paragon Home Video boxes are enough.