Throughout his career, director Quentin Tarantino has been admirably consistent about his ambition to make ten films — no more, no less — and then move on to other fields. He once stated, “I like that I will leave a ten-film filmography… it’s not etched in stone, but that is the plan. If I get to the tenth, do a good job and don’t screw it up, well that sounds like a good way to end the old career.” He was savvy enough to include a caveat: “if, later on, I come across a good movie, I won’t not do it just because I said I wouldn’t.” He concluded, “But ten and done, leaving them wanting more — that sounds right.”

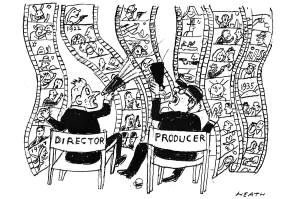

Thus it is that the news that Tarantino’s tenth film, The Movie Critic, will also be his last will be greeted with mixed emotions by his admirers and detractors alike. Details on his latest picture are sketchy, but it is said to be a period piece (as with all his films since 2009’s Inglourious Basterds) set in the Seventies and revolving around a powerful female film critic, perhaps a fictionalized version of the New Yorker’s legendary Pauline Kael.

This sounds as if it will eschew the usual violence and unpleasantness that Tarantino’s films are synonymous with. The only murders Kael committed were to careers with her sharpened quill. But as ever with Tarantino, revisionism and subversions of expectations are likely to be in the cards, and when the film appears in 2025 or so, it will no doubt be one of the most-anticipated releases of the year.

Yet is it such a terrible thing that it could be Tarantino’s farewell? For a start, the director has already broadened out into other spheres: he published the novelization of Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood in 2021, and a typically eclectic and eccentric work of memoir and film criticism, Cinema Speculation, last year. And for another, before he makes The Movie Critic, he has suggested that he will make an eight-part television series, details of which are elusive but place him in the vanguard of other filmmakers who have found freedom in that medium, everyone from Jane Campion to Danny Boyle. The noted cineaste is also never going to disappear from public view. It is inconceivable that he will not continue to offer his opinions on contemporary and classic cinema in every forum that is available to him.

There is also the sense with Tarantino — and this might be heresy, but what the hell — that he is beginning to run out of ideas. Since the Kill Bill films, his work has been commercially successful. Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood made $377 million worldwide, a staggering amount for an ultraviolent, 160-minute ode to Sixties genre cinema that ends (spoiler alert) with two young women being brutally killed, albeit deservedly so in the warped alternate universe that is depicted with such relish onscreen. But his movies have also repeated tropes and ideas with increasingly weary returns. He still attracts the biggest stars in the industry, many of whom are lured by the opportunity to deliver his endlessly quotable dialogue, but arguably not since Pulp Fiction has one of his films made a truly indelible mark on popular culture. The world has moved on considerably since the mid-Nineties; Tarantino, it appears, has not.

We can only hope that The Movie Critic is good. Tarantino films that feature female leads, including Jackie Brown and Kill Bill, tend to be better than the more macho entries in his filmography, and the potential opportunity to see his regular star Uma Thurman as Kael is an undeniably exciting one. Yet even at a time when movies are sagging, the knowledge that one of its most iconic — if derivative — practitioners has decided that his days in its service are numbered may be a wise example of jumping before he is pushed. And, as he says, he can always come back if he so chooses.