Winston Churchill looked forward to an expansive lunch. He was in his late seventies, prime minister for a second time, and this cabinet meeting was dragging on. It was nearly one o’clock and they were down to the eleventh item on the agenda, a memorandum on town planning. Wearily, Churchill said:

‘Ah yes, I know town planning, densities, broad vistas, open spaces…give me the romance of the 18th-century alley with its dark corners, where footpads lurk.’

It is possible to have this exact feeling watching cable news today. Somehow, you’re watching CNN or MSNBC, and some bloviating no-mark like Don Lemon or Chris Hayes or Ezra Klein is grimacing through air time. You are well aware than none of these people ever spun a lovely phrase, likely know not a stanza of poetry by heart, have used the word ‘wonk’ approvingly and write and speak in an English so dull and mechanical it reads and sounds like an IKEA instruction manual.

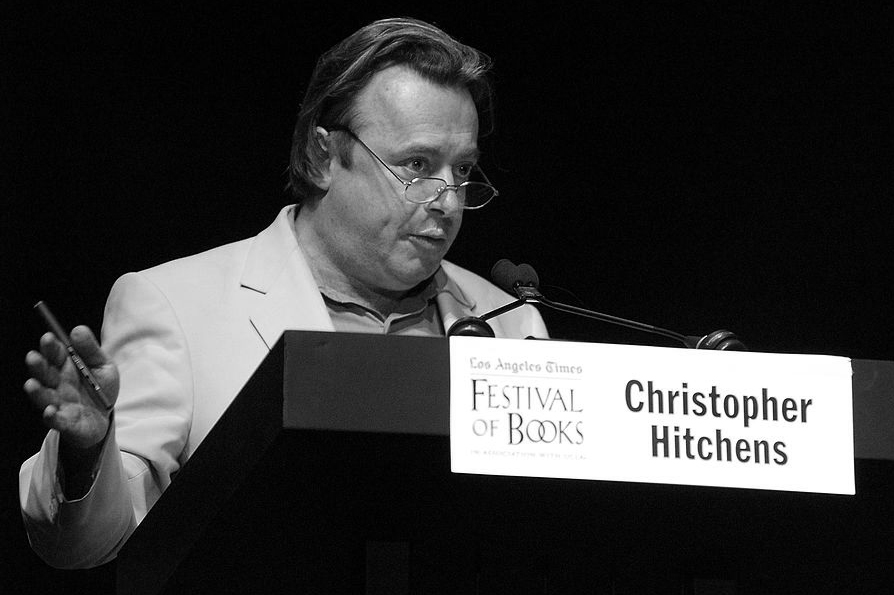

The natural reaction here is: Give me a Hitchens! Resurrect the late Christopher Hitchens and lever him back into the television studios and onto the airwaves. Resurrect the product of those classical dojos of English upper-class training (boarding school and Balliol) and set him furiously loose on the topics of the day. Give me Hitchens’s pointed, smartass raillery over the lamentable journalistic equivalent of town planning any day. If we must have cable news let us have a Hitchens to enliven it.

Christopher Hitchens, essayist, author and unwitting YouTuber died on December 15, 2011, one day after official ceremonies in Baghdad formally ended the Iraq war. A radical for much of his life, in his writing and speaking he wielded the radical weapons of obscenity and irony with great force. It is hard to know if he would have found the symmetry of his death with the ‘end’ of that difficult war – a war he kicked for with both Wellington boots – obscene or ironic.

Hitchens passed away near the peak of his celebrity, if not his powers. His memoir Hitch-22 (2010) was lumpy, uneven, mildly irritating but bestselling nevertheless. His last collection of journalism Arguably (2011) was massive but not quite massive enough to hide all the instances where Hitchens was happy to quote himself without embarrassment. The man of letters was becoming a heavy, even boring writer – the man of lead. As Michael Wolff noted in 2013, in one of the first major pieces on Hitchens after his death that didn’t take the form of an encomium:

‘Much of the work was repetitive and boilerplate, the same subjects recast for different outlets. The myriad essays to be pontifical, full of moral dudgeon and high virtue and not a lot of surprises.’

Writing became less important to Hitchens as his career progressed. What mattered more, especially once the planes struck the towers, was being on the right side of history. After spending much of his career chittering away in the long grass with other lefty grasshoppers, Hitchens went all in for the Bush administration, all in for the war in Iraq. In this guise as the hammer of Saddam, the scourge of ‘Islamofascism’ and the savior of the Kurds, he attempted to reclaim the role of the revolutionary from those on the left who were too prissy to live up to it:

‘…it became evident that the only historical revolution with any verve left in it, or any example to offer others, was the American one.’

When the American ‘example’ was exported abroad it did not take quite as well to Iraq as Ahmed Chalabi, Paul Wolfowitz and Hitchens thought it would. (‘Stuff happens!’ is how Donald Rumsfeld put it as Baghdad began to eat itself in 2003. ‘It’s untidy, and freedom’s untidy.’ One pictures Hitchens watching this and squirming with distaste.) He argued for war with all the sulfurous fervor of the brilliant radical, but its failure left him looking like all the other advocates of The Project for The New American Century: think Carrie at the end of that prom.

Hitchens’s next target was God, who he treated as a synonym for Saddam Hussein in his hugely successful God is not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything (2007). Along with Daniel Dennett, Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris, Hitchens became one of the merchants of New Atheism – a sort-of-movement that championed science, rationality and Enlightenment values against the offenses of religion, and Islam in particular. Hitchens was the group’s feckless uncle, its humanist soul and its freewheeling bombardier, cracking jokes, charismatically vouching for the potency of Johnnie Walker Black Label, and saying ‘fuck you’ in no uncertain terms to monotheism.

Since Hitchens’s death New Atheism has lost most of its charm and much of its momentum. Handling Islam with the same vitriol they treated every other religion with became less and less fashionable and more ‘problematic’ as the dishonest 2010s slouched onwards. Hitchens’s term ‘Islamofascism’ is not one to throw about if you want to attend a stress free dinner party. ‘Islamophobia’ – a notion Hitchens utterly despised – is hardly without controversy, but it is becoming more legitimate, mainstream and defined in law.

The oddness of Hitchens means that it is quite possible to imagine that, were he alive today, he would be writing a venomous feuilleton about ‘Londonistan’ for Breitbart as well as 3,000 words about the legacy of Rosa Luxemburg for Jacobin. His old friend Martin Amis said in 2017, ‘if Christopher Hitchens were alive today, he would be the leading voice…of the resistance [to President Trump].’

Well, perhaps. It is far easier to see Hitchens being slapped, slagged boxed, needled, cuffed and tossed around by sad Twitter partisans and slippery blue-tick hacks for things he said and wrote in the past. If you think I’m exaggerating then consider Michelle Obama’s blockbuster memoir Becoming (2018), which contains a bitchy aside on Hitchens:

‘He tore into college-age me, suggesting I’d been unduly influenced by radical black thinkers and furthermore was a crappy writer…it was a small-minded insult, sure, but his mocking of my intellect, his marginalizing of my young self, carried with it a larger dismissiveness…I was being painted not simply as an outsider but as fully “other”, so foreign that even my language couldn’t be recognized.’

Some things are clear from the passage. Firstly, as Hitchens argued back in 2008, Michelle Obama is a crappy writer (‘furthermore’? ‘sure’? ‘marginalizing’?). Secondly, she thinks Hitchens’s arguments were at least racially condescending, if not outright racist abuse. If Michelle Obama is this thin-skinned after the slings and arrows of two terms as FLOTUS, then you can comprehend the kind of relentless dunking Hitchens and those who published him would have received on Twitter. Martin: he wouldn’t have been allowed to lead the Resistance.

His stock would have gone down, or at least changed. Maybe it wouldn’t be so terrible: Hitch on Joe Rogan; Hitch on the Rubin Report; an evening with Hitch, Sam Harris and Jordan Peterson…he would have attacked identity politics, as he did throughout his life:

‘Beware of identity politics. I’ll re-phrase that: have nothing to do with identity politics. I remember very well the first time I heard the saying “The Personal is Political”…People began to stand up at meetings and orate about how they felt, not about what or how they thought…it was the dense and boring and selfish people who had always seen identity politics as their big chance.’

Would he have drifted towards Trumpism? Would he have become, as Matthew Yglesias put it, ‘the leading pro-Trump columnist in America’? A temptingly bonkers idea until you remember that Hitchens sprang from the fecund soils of British snobbery. Trump’s undoubted vulgarity would be the great offense. (During his last visit to Britain Trump reportedly stopped at the white marble slab in Westminster Abbey that commemorates Lord Byron. He looked at it for a while, then asked what the flooring was made from. Hitchens might have produced a brutal thousand words on this.)

Though they rarely have his flair for expression, most pundits (and these days a pundit is anyone with an internet connection) share Hitchens’s absolute certainty that they’re right about whatever tidbit they’re chewing on. The nadir of this trending contrarianism came when Bill Maher described Milo Yiannopoulos as ‘the young, gay Christopher Hitchens.’ And, awful as it is to admit it, wasn’t there a dash – just a dash – of truth to that judgment?

Winners and losers; friends and enemies; right and wrong; strong opinions everywhere. It feels like we’ve ended up dwelling in a landscape moulded to Hitch-like contours and vistas – even if he would have hated living in it.