Displays of wanton brutality and heroic resistance in the Russo-Ukrainian War of 2022 have prompted some in the West to proclaim a moment of “moral clarity.” Some caution might be wise here, since moral clarity in world affairs is not always as clear or as moral as its claimants think. It was Soviet ideology, succeeding czarist imperialism, that for so long smothered Ukraine, along with the other captive nations consigned to Stalin at Yalta. As Ukraine may now be slipping captivity at last, the West rejoices. But how clear is the clarity?

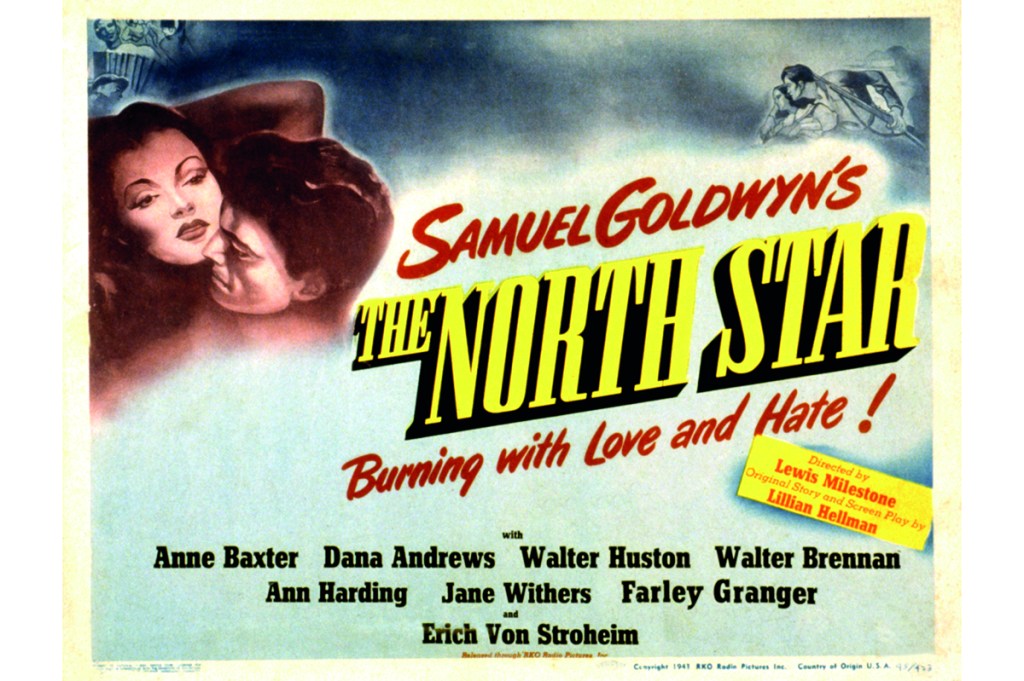

History’s players sometimes switch roles even from one act to the next. It has not, for example, always been brutal Russians that heroic Ukrainians went up against. Eighty-one years ago, it was brutal Germans. (Until, that is, some Ukrainians switched loyalties to fight with the Germans against the Russians.) When Hitler turned on Stalin and invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Ukraine and Belarus, both then Soviet “socialist republics,” took the blow first. Historians have told this story in full, but at the time many in the West learned about it through Soviet propaganda, courtesy of Hollywood. The standout example was the Samuel Goldwyn film from 1943, The North Star, its story and screenplay from the pen of communist fellow traveler Lillian Hellman. The Roosevelt administration hoped to make the Soviet Union — the West’s ally of convenience — also appear to be its friend, which FDR probably believed it was. Hellman dramatized Ukrainian resistance to further the cause.

A black-and-white film in all senses, The North Star begins with an idyllic picture of a happily collectivized Ukrainian village on the eve of the German invasion. But for the thatched roofs we could be in Iowa, with fat cattle, lots to eat, a radio in the parlor, comely farmers’ daughters and handsome sons. The A-list American cast, including Anne Baxter, Walter Huston and Walter Brennan, makes it almost believable. The story begins with friends from high school heading off on a graduation trip to Kyiv. Good comrades all, they commence their four-day walk singing: “We’re the younger generation and the future of the nation.” Singing abounds in The North Star, with music by Aaron Copland and lyrics by George Gershwin, but the sky soon darkens and Stukas rain down terror. A child is killed: “We are not young anymore,” the students declare. “It is time for revenge.”

Back home, the village divides in two groups. Men of fighting age mount up to form a guerrilla cavalry. Women and children and the old stay behind to burn anything that might be of use to the invaders. The Germans turn out to be a medical unit, which sounds benign but turns out to be the opposite. As they were reported to have done in Poland, the Nazis intend to commandeer the hospital and use village children for live blood transfusions to German wounded.

When word gets out that a little boy has died in this ghoulish process, the guerrillas counterattack to save the others. The local doctor joins them and shoots the German doctors responsible. Triumphant for the moment, the Ukrainians vow to fight on until “the last fascist is driven from our land.” Two of the young people vow that “we’ll make this the last war. We’ll make a free world for all.”

The North Star delivered moral clarity of a kind, briefly. With the thinness of all propaganda, however, this would not last much beyond 1945, when the Russians went from friends to enemies. Hellman made no mention of the Holodomor, the mass starvation of millions of Ukrainians in the course of Stalin’s forced collectivization of Soviet agriculture in the early 1930s. In the 1940s, when The North Star was made, Germans were the West’s enemy number one, and Hellman portrayed them to be as wicked as possible: as abusers of children and murderers of innocents. German doctors, acting criminally and under orders, fill their waiting rooms with young victims. Among them is a pretty girl who, as she is hauled to her doom, grasps vainly at the door frame in resistance. The shot still horrifies.

Lately, long after Ukraine’s travails as propagandized in The North Star, Western leaders are in high dudgeon over new Russian war crimes there — indiscriminate bombardment, besieging of cities, targeting of civilians — many of which one way or another were committed by both sides in the Second World War, the losers alone being held to account, and spottily at that.

Just before catastrophe strikes his village, Kolya Simonov, one of The North Star’s idealistic teenagers who will soon grow up fast, exclaims joyously: “I am a citizen of this country and I intend to go forward with it: ours is a new world.” You may judge this propaganda or patriotism. Kolya was among the lucky ones, who at least had a chance.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2022 World edition.