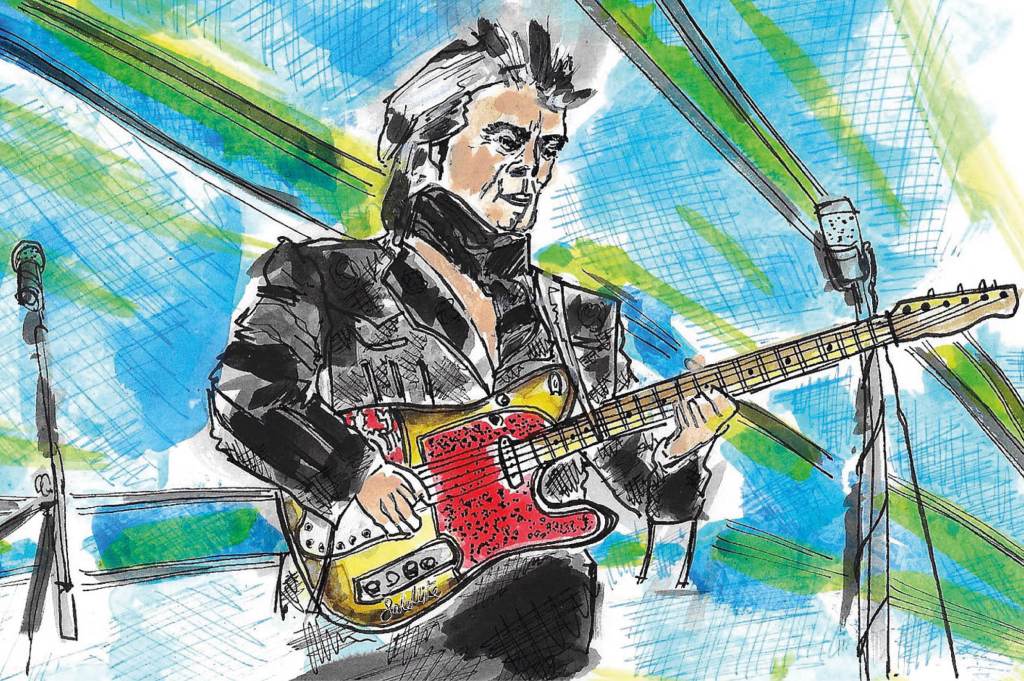

He stands five-foot-seven in his stocking feet — five-nine in boots — but with Clarence White’s Telecaster slung around his neck and a thick head of gray hair roostered up, he looks ten feet tall.

John Marty Stuart has plucked the strings of every major figure in country music. Growing up in Philadelphia, Mississippi, his heroes were bluegrass legend Lester Flatt and American prophet Johnny Cash. Before going out on his own, Stuart only had two jobs: he joined Flatt’s band in 1972 as a fourteen-year-old mandolin virtuoso, and after Flatt retired in 1978, he joined Cash’s band as a guitarist. Five years later, he married Cash’s daughter, Cindy, and a decade after that relationship ended, he married Country Music Hall of Famer Connie Smith, fulfilling the plan he’d announced after seeing her perform at the Choctaw Indian Reservation in Neshoba County when he was twelve.

While touring as a teenager with Flatt, he lived with fellow bandmate Roland White, spending his free time going through Roland’s enormous record collection. Stuart was surprised to find that Roland had several records by the Byrds among his shelves of bluegrass albums.

“How come you have so many Byrds records?” Stuart asked.

“My brother Clarence plays guitar in the band,” said Roland.

Listening to the Byrds’s groundbreaking country-rock album, Sweetheart of the Rodeo, Stuart heard Clarence White’s famous Pull-String Telecaster on the opening track, “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere.”

The first of its kind, this Fender Telecaster had been equipped with a device invented by Byrds drummer Gene Parsons and Clarence White himself: the Parsons-White Pull-String. This complex system of springs and levers inside the body of the guitar allowed a player to raise the B-string a whole step by pressing down on the guitar’s neck. The benefit of this contraption is that a guitarist can hold chord shapes and perform bends without having to manipulate the B-string with his fingers. In other words, the Parsons-White Pull-String turned a Fender Telecaster into a pedal steel: a guitar outfitted with this invention could produce those haunting high and lonesome sounds we hear in the opening bars of “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere.”

The Parsons-White Pull-String has been redesigned by world-class luthiers like Joe Glaser; some Telecasters now come factory-equipped with them. For $650, you can send your Telecaster to Glaser in Nashville and he’ll install one of his benders, a process that takes him about half an hour.

When Clarence was hit and killed by a drunk driver in 1973, Marty Stuart felt the loss was equal to that of other prematurely departed musicians of the 1960s.

There went the life of somebody who I have no doubt in my mind could have been revered in the same pantheon as Jimi Hendrix or any of those other guys in that league, because I know Clarence had that much in him.

In 1980, White’s widow, Susie, called Stuart to let him know she was selling some of Clarence’s things. Stuart, a longtime collector of country memorabilia, told her he’d buy anything she was selling.

She led him around her home, showing him a Fender Stratocaster that had belonged to Clarence, a Nudie suit that he’d worn when he was in the Byrds, and various other mementos.

Stuart asked, “Is the Pull-String still here?”

“That’s the guitar you really want, isn’t it?” Susie said.

Stuart was shocked. “I’d like to just hold it,” he said.

The iconic Telecaster was in a case in the attic, missing strings, hadn’t been played in years.

Stuart restrung the guitar, spent a few hours playing it, and then Susie walked in and told him she’d sell him Clarence’s Pull-String Telecaster along with the other Byrds’ memorabilia.

The musician produced his checkbook, laid it on the table, and told her, “Whatever number you put in within reason is fine with me and if it’s not within reason, my mom works at a bank — I’ll get a loan.”

Susie retrieved a pen and wrote 1,450 dollars.

Stuart shook his head. He said, “Susie, the E-string on this guitar is worth—”

“I know what the guitar is worth,” she said.

He pleaded with her to take more money, but she refused.

“I think Clarence would want you to have it,” she told him.

“I only met him one time,” Stuart reminded her.

“You’ll take care of it,” she said, “and honor it.”

Marty Stuart has kept his word. In 2010, he recorded an instrumental called “Hummingbyrd” on his album Ghost Train with his band the Fabulous Superlatives. The song won a Grammy Award and is a tribute not only to the Byrds, but to Clarence White and the Pull-String Telecaster which Stuart used on the track.

His latest album with the Fabulous Superlatives, the extraordinary Altitude, is shaped as much by White’s Telecaster as it has by Stuart’s expert songwriting and the band’s prodigious talent. Stuart refers to the Pull-String Tele as the “fifth member of the band” and you can hear those Byrdsesque guitar licks on nearly every track, a strain of White’s high and lonesome voice still pulling at the listener’s heart. Stuart and the Superlatives are now on tour and while audiences attending their shows come to witness the band’s virtuosity, a number of people buy tickets just to see and hear Clarence White’s Telecaster, which continues its almost sixty-year bender.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2023 World edition.

Leave a Reply