On January 23, Dr Stephen D. O’Leary, a retired professor of communications at the University of Southern California, posted a poem by George Eliot to his Facebook page. It begins: ‘O May I join the choir invisible / Of those immortal dead who live again’.

For 25 years Stephen was one of my closest friends in the world. I still can’t believe that I have to use the past tense when talking about him. He pressed ‘send’ on that Facebook post at 4:47 p.m. At one in the morning he joined the choir invisible.

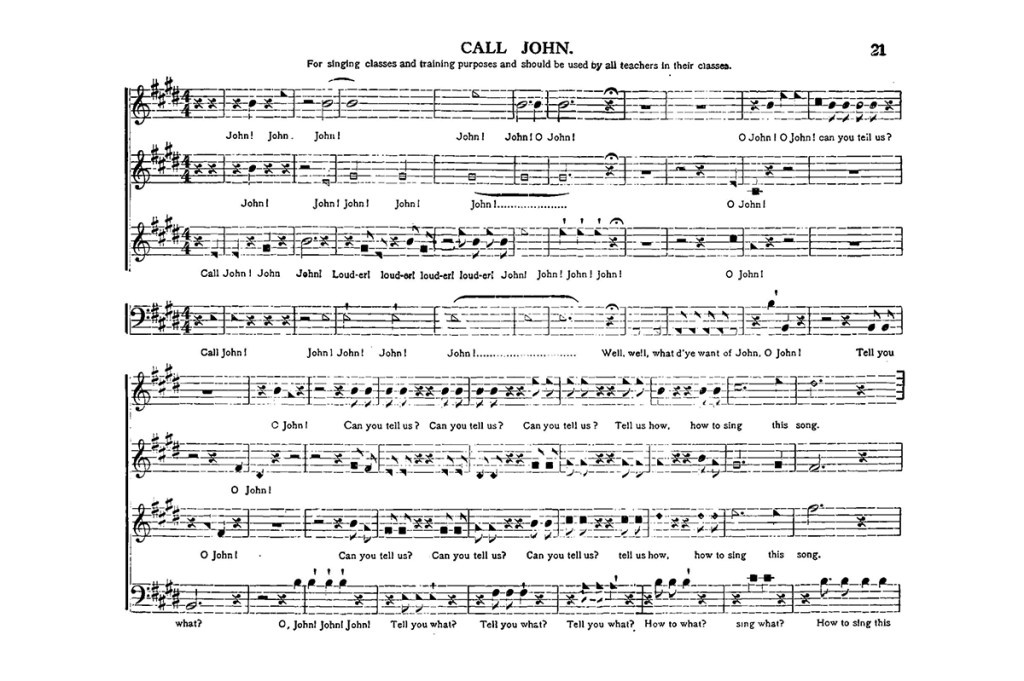

Although his heart attack was unexpected, we knew we were going to lose him. He called me the day after he was diagnosed with liver cancer. ‘I’m not afraid of dying. It’s going to be interesting,’ he said. He posted the Eliot poem because it’s the text of the ‘Farewell Anthem’, one of the songs in The Sacred Harp, an 1844 tunebook of hymns for communal singing in secular settings. It has its own notation: different shapes for the notes of the scale, intended to make reading music easier. This ‘shape-note’ singing started in New England in the 18th century, but it was The Sacred Harp that spread it like wildfire across the South and West.

Shape-note singing was one of Stephen O’Leary’s passions. He did nothing by halves, devouring Aristotle, Tudor polyphony, pizza and red wine. He spent the last weekend of his life at the 32nd California Sacred Harp Convention. His Facebook page carried video of his small, tubby frame bearing the strain of illness but still producing the loudest noise in the room.

The gathering looked strange: participants facing each other in a ‘hollow square’, their hands rising and falling like those of puppets. It sounded even stranger. You could barely hear the harmonies, so intent were the singers on drowning each other out. The men sounded as if they could awaken a whole neighborhood from their shower. No wonder Stephen loved it: his own bathroom arias had us all begging for mercy.

I went online and listened to recordings of the most ‘authentic’ shape-note singing in America, from the giant Okefenokee Swamp on the border between Georgia and Florida. They make Stephen’s friends sound like the choir of King’s College, Cambridge. Voices cracked with age collide with each other; the effect is ugly until suddenly you’re swept away. To hear anything like it in Britain you’d have to visit the Western Isles of Scotland, where Presbyterians sing the Psalms in Gaelic. Like Sacred Harp singers, no one hits precisely the same note at the same time.

There’s something puzzling about both traditions. How did strict Protestants singing out of tune manage to create such an emotionally satisfying noise? And why is Sacred Harp flourishing while the haunting choral worship of Lewis and other islands is almost extinct?

One difference is that shape-singers are gripped by what the folklorist Laurie Kay Sommers calls ‘the sheer joy of hollering’. A visitor to the 1930 Texas Sacred Harp convention described it as ‘a veritable and ardent love feast’, in which children were smothered in kisses and old men, laughing and sweating, gave out a ‘short staccato whoop or yip and yell’.

Stephen’s great friend Jim Friedrich, an Episcopal priest, describes shape-note singing as ‘a volcanic eruption of sound that blasts and sears you like heat from a forge.’ He’d like to send every Episcopal musician to a shape-note convention, to shock them out of their ‘tepid, even anemic’ hymn singing.

***

Get three months of The Spectator for just $9.99 — plus a Spectator Parker pen

***

But, as he points out, there is no theology at singings. The Sacred Harp Musical Heritage Association describes them as ‘a deeply spiritual experience for all involved, which functions as a religious observance for many singers’.

Note the distinction between spiritual and religious. At modern shape-note singings, conservative churchgoers and urban liberals — including atheists and the openly gay— bellow out old-fashioned hymns together. Not even Trump (whom Stephen despised) can divide them, because you don’t talk politics. Stephen chose the ‘Farewell Anthem’ as a way of preparing his fellow singers for the news about his health, which he announced on Facebook a couple of days later. He added: ‘Some people find the songs morbid and strange, but I never feel so alive as I do when singing about death at the top of my lungs in a roomful of people I love…I hope to sing with all of you sometime soon — here on earth, long before I go to sing with the “choir invisible.”’

It wasn’t to be. I gather that he had the heart attack while cooking eggs in the dead of night, a very Stephen thing to do. ‘He likely went out singing,’ wrote his sister, Anne. More than likely, I’d say. He was addicted to the joy of hollering. The world is too quiet without him.