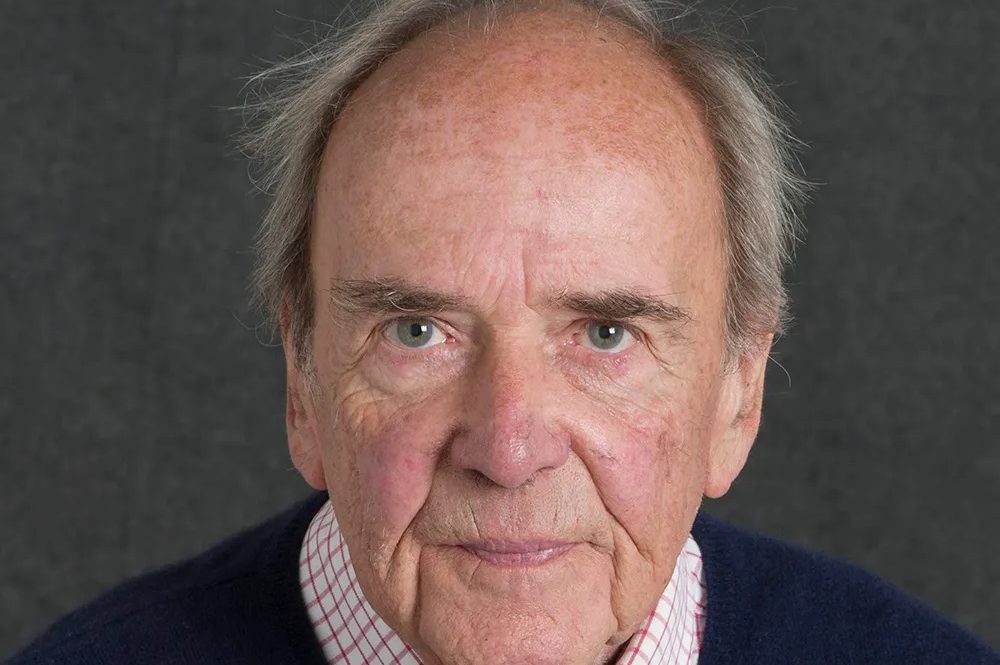

Roald Dahl was, in many respects, a horrible man. He was a narcissist, a bully, a liar, an antisemite, a tax-dodger, a faithless husband and — if his daughter’s account is to be believed — a cruel and thoughtless father.

None of which has anything whatever to do, it scarcely needs saying, with the content of his books. But for once it’s the contents of the books, rather than the adult prejudices of the author, that are drawing heat.

Dahl’s publisher, as the Telegraph reported at the weekend, has quietly reissued edited versions of Dahl’s canon: “This book was written many years ago, and so we regularly review the language to ensure that it can continue to be enjoyed by all today.” Many dozens of small changes have been made by sensitivity readers to remove sexism, racism, ableism, fat-shaming and violence, and the resulting brouhaha has hit the culture wars right in the sweet spot.

Is this censorship? Not in the usual sense that we use the term. The original texts are not being burned, nor is there any move to purge them from libraries or bookshops. There is no legal or institutional pressure being applied to stifle free speech. In this case the copyright holder (the Dahl Estate, as was, and now Netflix) is choosing to reissue an altered version of the work. Dahl himself, as the original report of this story was scrupulous enough to admit, did the same thing while he was alive, agreeing to “de-Negro” (his phrase) the Oompa Loompas in later editions of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The publication history of Little Black Sambo, arguably a much hotter potato, has involved a whole series of redactions and revisions, mostly to the illustrations.

The motivation behind the re-editing of Dahl isn’t some woke twenty-first-century aberration, either. Adults have been deeply anxious about the moral content of children’s books since children’s books began. They have sensed, probably rightly, that stories shape young minds. A few centuries back when, in the unimprovable phrase of one critic, the market was cornered by “Calvinists of unrelenting severity,” most children’s books were designed to scare the original sin right out of their readers. In the 1818 bestseller The History of the Fairchild Family, a family outing to a gibbet is arranged to turn the children’s thoughts to repentance — and one little girl is burned to death as a lesson on the importance of obeying one’s parents. Frances Hodgson Burnett remembered the books of her own childhood “containing memoirs of dreadful children who died early of complicated diseases.”

So this panic is old wine in new bottles, and we should try to look at it coolly. You make a weak case, I think, if you insist that you “vandalize” Dahl’s books beyond recognition by the snipping of the odd phrase here or there. Some poetry is that vulnerable; relatively little prose is. These stories aren’t sacred texts, and you do them no favors by fetishizing them as if they were. Stories are robust things. Is giving up a little of the books’ distinctiveness a price worth paying to try to help create a culture where overweight children aren’t bullied in the playground? That’s the calculation that the publishers have made, and it isn’t one to be dismissed out of hand. Fine-sounding principles about the inviolable sanctity of Art are no comfort to an eight-year-old in tears.

And yet, and yet. I think most of us will feel uneasy — I know I do — at the idea that Dahl’s spiky and surprising prose, no matter how little at first, is to be made blander by a succession of anonymous, pedestrian editors selected for ideology rather than inspiration. Many of the changes that have come to light have been clumsy and, in some cases, entirely senseless. You can see why the editors are down on Dahl’s fat-shaming, though Augustus Gloop is no longer fat but “enormous.” Sexed terms of abuse are out (“old hag” is verboten). But the editors also seem to be fighting shy of the words black and white even when they don’t relate to race, and to want to eliminate every gender-specific term they can get away with. Having “Cloud-Men” rather than “Cloud-People” won’t strike most of us as offensively heteronormative. That’s just feeble.

The fantasy you can create right-thinking in a population by controlling the literature it consumes is a mistake that has been made by any number of unsavory regimes: it both overestimates and underestimates the power of storytelling. More immediately, once you cede the principle, where does it end — with Dahl’s demonic storytelling energy smoothed over years to a dull domestic hum? Especially given that moral norms will continue to change, especially when you look at a writer whose appeal is so bound up with his questionable worldview as Dahl.

Even in his own age he wasn’t really a modern writer at all. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, with its cast of grotesque children embodying single personality traits and receiving comeuppances by turn, punctuated by choral interludes from the Oompa-Loompas, is like an early-modern comedy of humors. Dahl’s career-long equation of physical with moral beauty — a particular focus of the edited versions — is as old as the fairy tales from which children’s stories still draw their archetypal power. Princes are handsome, princesses are fair, witches are ugly and monsters are monstrous.

Which is to say, not only where do you end, but where do you begin? Almost every kids’ classic more than thirty years old would be a candidate for the blue pencil. We all know about Enid Blyton’s golliwogs, Tolkien’s orcs and C.S. Lewis’s giving the boys swords and the girls first-aid kits at the final battle. But even in so right-on a writer as E. Nesbit, there’s gender and racial stereotyping all over the place (the Bastable children meet a wheedling Jewish moneylender), and Victorian/Edwardian assumptions about class shape her worlds. Right into the 1980s, sexual objectification and low-key racial othering, as it’s now called, was the norm (Robert Westall’s Futuretrack Five, from 1983, has casual mention of “an old Negress”). Run a Dahl-style edit through the canon of children’s literature and you’ll end up with precious little left, a lot of imaginative specificity lost as collateral damage, and no sense of the history of the canon.

Dahl is also, it seems to me, something of a special case. The cruelty in his books isn’t accidental: it’s their special sauce. And it isn’t something that the adult writer imposes on the tender minds of children, whatever the sensitivity reader might fear: it’s something the adult writer draws from those children. The genius of Dahl was that he recognized the streak of cruelty in children because, like so many children’s writers, he had a hotline to his own inner child. His books divided the world into goodies and baddies, and once you were in the latter category you were going to get your lumps. Nobody mourns when Aunts Spiker and Sponge are squashed flat by the giant peach. Bad tempered grandmothers are fair game for unlicensed pharmaceutical experiments. Spoilt, vulgar, greedy children will be traumatized in imaginative ways, and the Oompa Loompas will sing choric songs of celebration. And the protagonist of The Witches, along with his stogie-smoking Norwegian granny, pursues a campaign against these blameless magic-dabbling ladies that is expressly genocidal. Part of Dahl’s readers’ pleasure in the wickedness of his villains is that it licenses the gleeful sadism of their comeuppances.

And there’s the funny thing. Dahl, victim of it though he might be, would have understood the psychological roots of cancel culture very well. Everyone who has ever watched a shaming taking place live on social media can attest to the thrill that adults get when they have decided that their moral righteousness gives them permission to be as cruel as they like.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.