Geography can be history and history geography — and sometimes the most obvious things are overlooked. Laurence C. Smith’s Rivers of Power endeavors to make us see beneath the surfaces of arterial waters and consider them as carriers of civilization and arbiters of destinies.

Rivers are elemental and ambivalent. They are frontiers and highways, destroyers and fertilizers, fishing grounds and spiritual metaphors, power-givers and flushers of poisons. They are the veins of terrains, which like our own veins carry oxygen or pathogens, and extinction when they fail. They inspired Babylonian and Roman legal codes, outlining ideas about access, drainage, fishing, irrigation, maintenance, navigation, pollution and sharing that still course through 21st-century jurisprudence. We may never step in the same river twice, but at least we have some notion of riverine rights and responsibilities.

This enthusiastic, occasionally gushing, author opens his hymn to hydrology ancient and modern with a descent into a 9th-century Nilometer, a great pit with a notched marble column, now under concrete in central Cairo, but once a confidential key to understanding the flow and volume of the river whose silts permitted sowing and whose droughts could mean death. The predictability the river offered allowed philosophy and pyramids — and authoritarian government and downstream dependence. In some countries today, reservoir and river levels are still state secret.

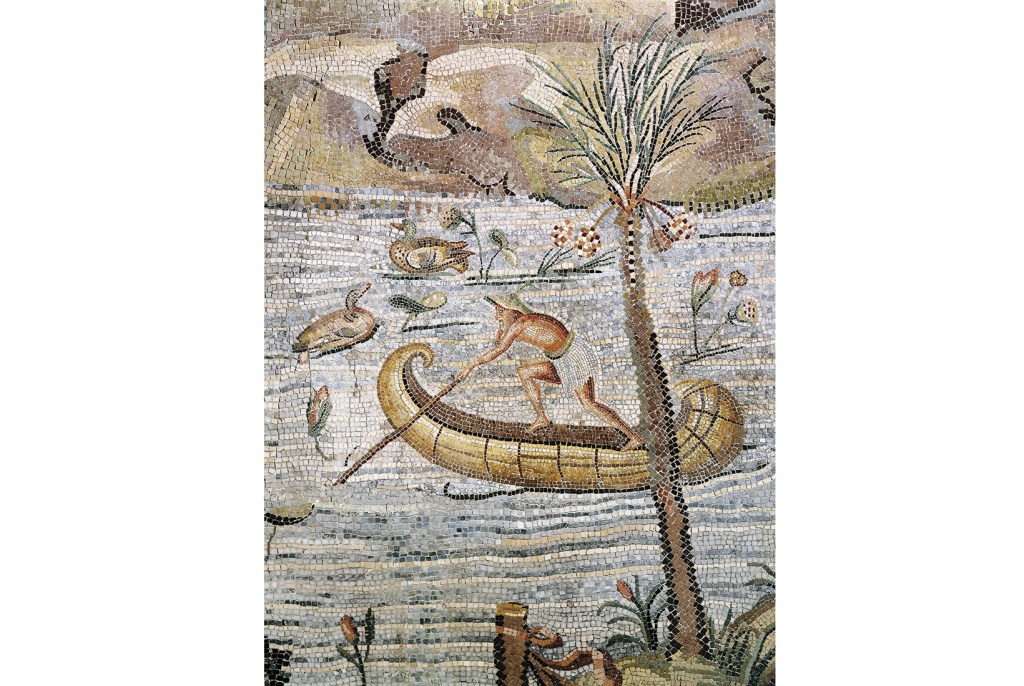

Before Egypt there had been Mesopotamia, powered by the Tigris and the Euphrates. As the Epic of Gilgamesh ruminates: ‘Ever the river has risen and brought us the flood, /The mayfly floating on the water.’ About the same time, the Harappans were overflowing along the Indus. And before then, people were planting rice, and writing, in the Yangtze and Yellow basins. Mycenaean bridges still straddle some Peleponnesian streams. Mystical Greeks ferried their dead over the Styx; Vikings sent theirs over the Gjöll; Hindus drifted theirs down the Ganges, and the Celts tossed votive swords into the Thames. Even for the physicist author, rivers can seem sentient — as if they ‘strive’, and have a ‘will’.

Humanity’s romans-fleuves have often been tales from the riverbank. Sixty-three percent of the world’s population lives within 20 miles of a major river, and the vast majority of ‘coastal’ cities are really river-delta conurbations. From Akkad to the Isis Caliphate, Noah to Yu the Great, the Rubicon to the Mekong, The Compleat Angler to the Lewis-Clark expedition, a river usually runs through it. Vitruvius devoted an entire volume of De Architectura to the management of water — a subject still pressing 1,800 years later to Alexander Pope, who extolled the ‘obedient rivers’ of aristocratic estates, and even more urgent in the past decades, when these once well-behaved waterways decanted devastation on to English towns.

Some of the earliest scientific speculations concerned the origins of the Nile; and Ecclesiastes 1:7 famously ponders the enigma — ‘All the rivers run into the sea, yet the sea is not full; unto the place from whence the rivers come, thither they return again.’ It was not until Pierre Perrault’s On the Origin of Springs (1674) that the principles of precipitation were established.

But it has only been very recently that we have begun to understand the extent and health of the Earth’s waters — thanks to cloud-computing, satellite and remote-sensing technologies, many deployed and developed by the admirably hands-on, legs-in Professor Smith. Composite imaging shows a worrying picture of appearances, disappearances and transformations, as humans with titanic earth-moving powers bridge, canalize, culvert, dam, divert, drain, drink and poison irreplaceable aqua vitae. Dead zones, toxic blooms and transgender fish fan out into the oceans from debouchments. Water shortages and sullying bring huge suffering, environmental cataclysm and often violent unrest. Even the sainted have gone to war over water — including Nelson Mandela, who sent troops to take a Lesotho dam. China wants Tibet mostly for water. Ethiopia’s plans for the Nile’s headwaters could mean another Egyptian eclipse. Water is even bitterly contested within countries — Los Angeles’s 1913 water-grab of the Owens River inspired Roman Polanski’s brilliantly seamy Chinatown.

Not all planned dams will be built. And Smith hopes that better understanding of how they function, and wildlife’s requirements, may mitigate effects: timed releases to mimic natural cycles, allowing sediment to pass through, and run-of-river dams to avoid the need for reservoirs. Some schemes might even bring benefits. Africa’s Trans-aqua project could help replenish Lake Chad, where too many desperate former fishermen are taking Islamist bait. Elsewhere, dams are being removed as outdated liabilities and rivers allowed to revert, with huge benefits for humans and wildlife.

Being close to running water reduces stress hormones and allows us to connect with the elements. Smith is greatly inspired by urban redevelopments that open up waterfronts; by advances in data-gathering and micro-hydropower; and by a general increasing awareness of rivers’ centrality to culture, ecology and economics. When the current crisis is over, we need to get outside and fall in love with rivers for ourselves.

This article was originally published in

The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.