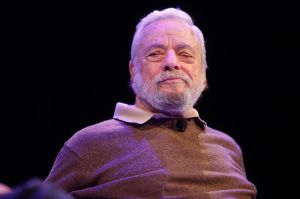

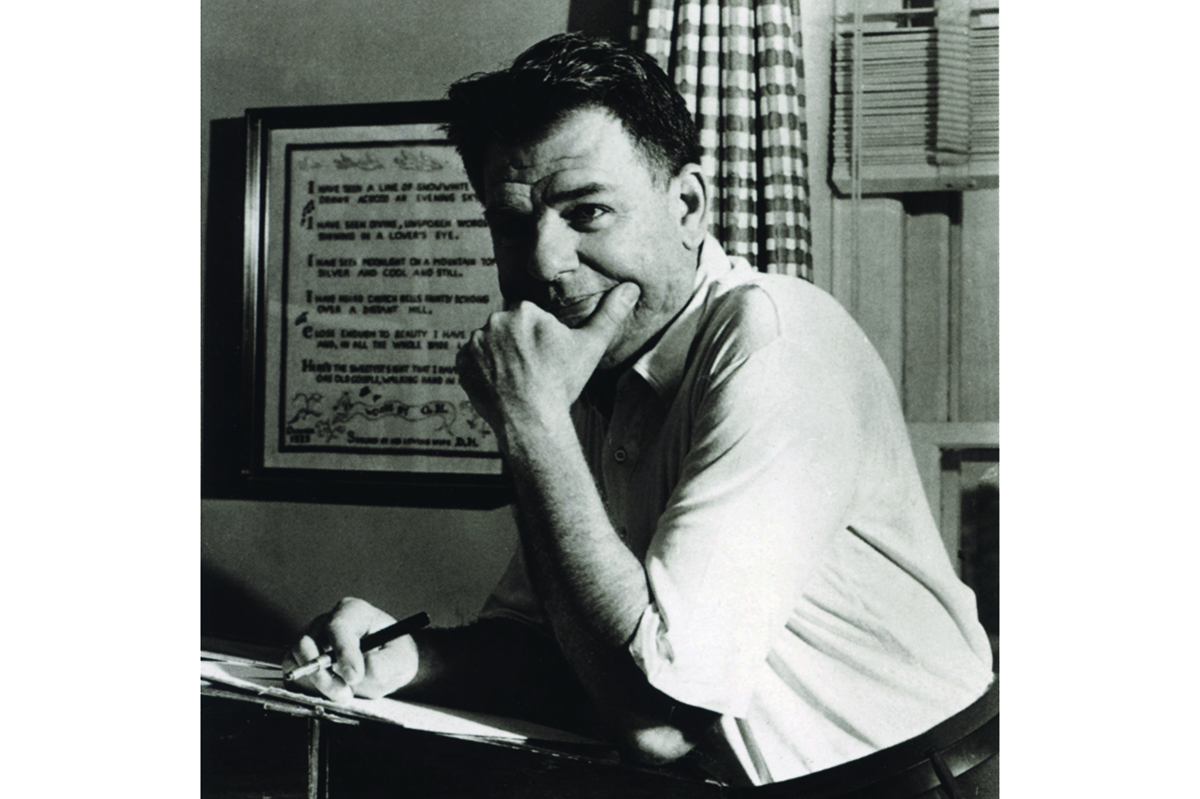

The composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim’s death at the age of ninety-one does more than simply rob the world of musical theater of its most distinguished practitioner. With the exception of Tom Stoppard, there was probably no greater figure in contemporary world drama. To mourn his passing, even at his extraordinary old age, is only to pay dutiful homage to one of the most extraordinarily diverse (in its usual meaning) and accomplished canons of work that any figure in English-language drama has ever produced.

He was born in New York City in 1930 and remained the most Manhattanite of talents all his life. Even as his subjects encompassed everything from Roman slaves conniving to win their freedom and homicidal Victorian barbers to deconstructed Grimm fairy tales and the life and work of Georges Seurat, there was no denying that the typical Sondheim musical was witty, deeply attuned to ironies great and small and, invariably, possessed of near-anguished sensibility and feeling underneath the martini-dry quips and suavity.

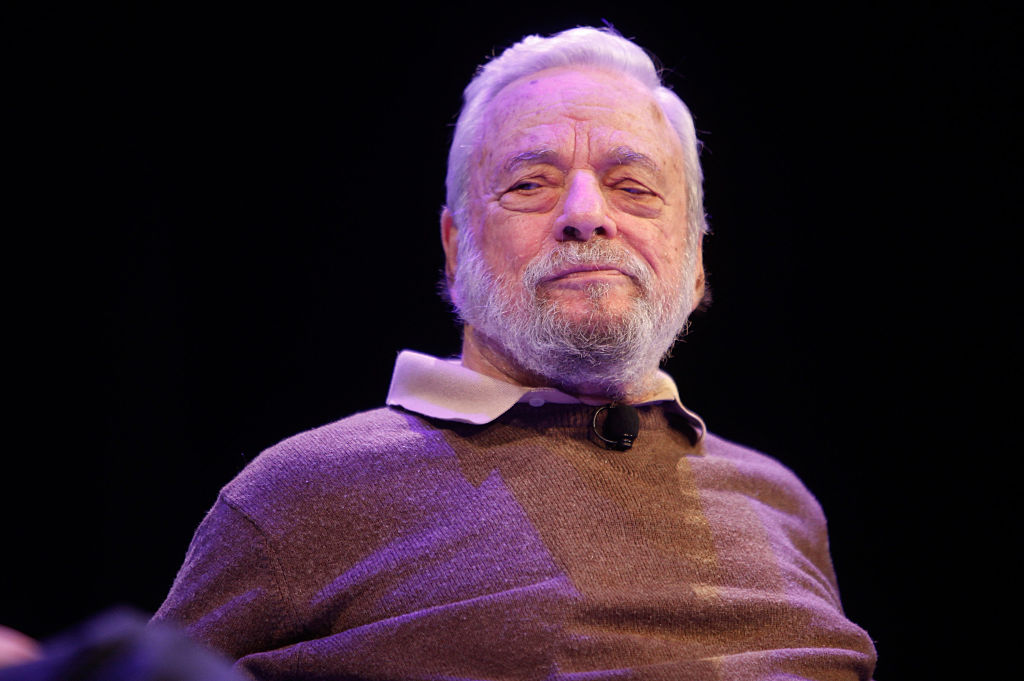

This suited Sondheim the man exceptionally well. He began his career young, after an apprentice period under the tutelage of Oscar Hammerstein II; he had befriended Hammerstein’s son James at school, and the experienced lyricist and playwright swiftly set about dismantling the juvenile would-be composer’s delusions of grandeur.

Sondheim wrote a comic musical, By George, while at school, and proudly asked Hammerstein to assess it on its own merits. The playwright was brutal: “It’s the worst thing I’ve ever seen.” But he was also compassionate: “If you want to know why it’s terrible, I’ll tell you.” Sondheim later remarked that the subsequent deconstruction of his apprentice work was quite invaluable: “In that afternoon I learned more about songwriting and the musical theater than most people learn in a lifetime.”

He had his first big break in 1957, at the age of twenty-seven, when his lyrics to Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story established him as a brilliantly versatile talent, even if he subsequently expressed ambivalence towards his work for the musical. He said of the line sung by the protagonist Maria, “it’s alarming how charming I feel,” that “That wouldn’t be unwelcome in Noël Coward’s living room. …I don’t know what a Puerto Rican street girl is doing singing a line like that.”

After contributing similarly distinguished lyrics to the show Gypsy, about the “exotic entertainer” Gypsy Rose Lee, Sondheim’s debut as both lyricist and composer came in 1962 with the Roman set farce A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum, which received enormous acclaim, won him a Tony award for best musical and was adapted into a successful film. And after that, as they say, Sondheim was away.

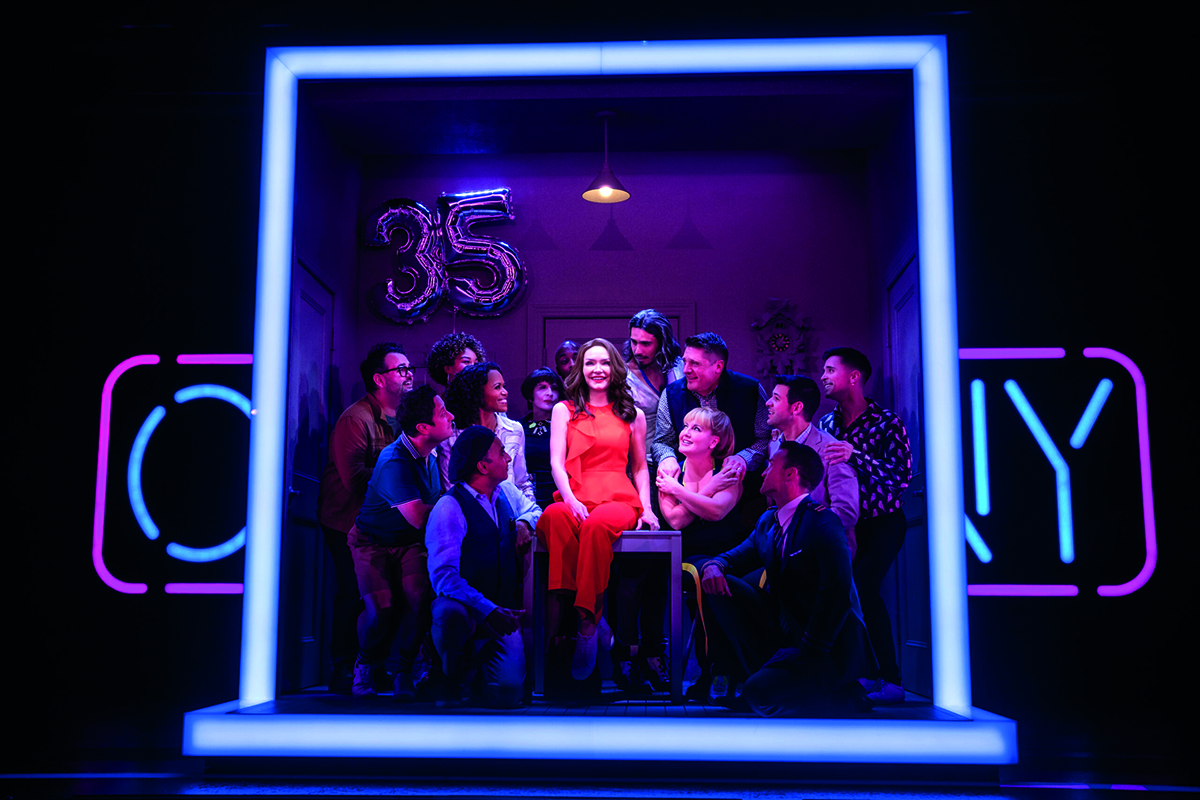

Thereafter, it’s personal taste as to which of Sondheim’s musicals one considers the best. Sweeney Todd might be his best known, thanks to the stupendously bloody Tim Burton movie, but the cognoscenti would argue for the likes of Follies, about the emotional turmoil of a group of former showgirls, or Company, his most “New York” musical, in its exploration of the inner psyche of a commitment-phobic thirty-five-year-old man, and his gradual realization that he has observed, rather than participated in, life.

Sondheim himself was a witty, wise figure, ever-ready with self-deprecating insights about his own work, even if he was shy about offering autobiographical interpretations of many of his songs. He was prolific but never a hack, versatile enough to have done everything from writing music for Warren Beatty films and compiling cryptic crosswords to co-scripting the intriguing 1973 noir pastiche The Last Of Sheila. Energetic until virtually the end, he attended first nights of revivals of Assassins and Company a matter of days before he died, along with giving a final interview to the New York Times in which he reflected “I’ve been very lucky.”

It would be hard not to agree. We shall not look upon his like again, and that is an enormous sadness, even as we consider the luck that we had to have had so much greatness from one man. But his work will endure forever, and that is a comfort, even as we mourn the loss of the great, complex figure who created it.