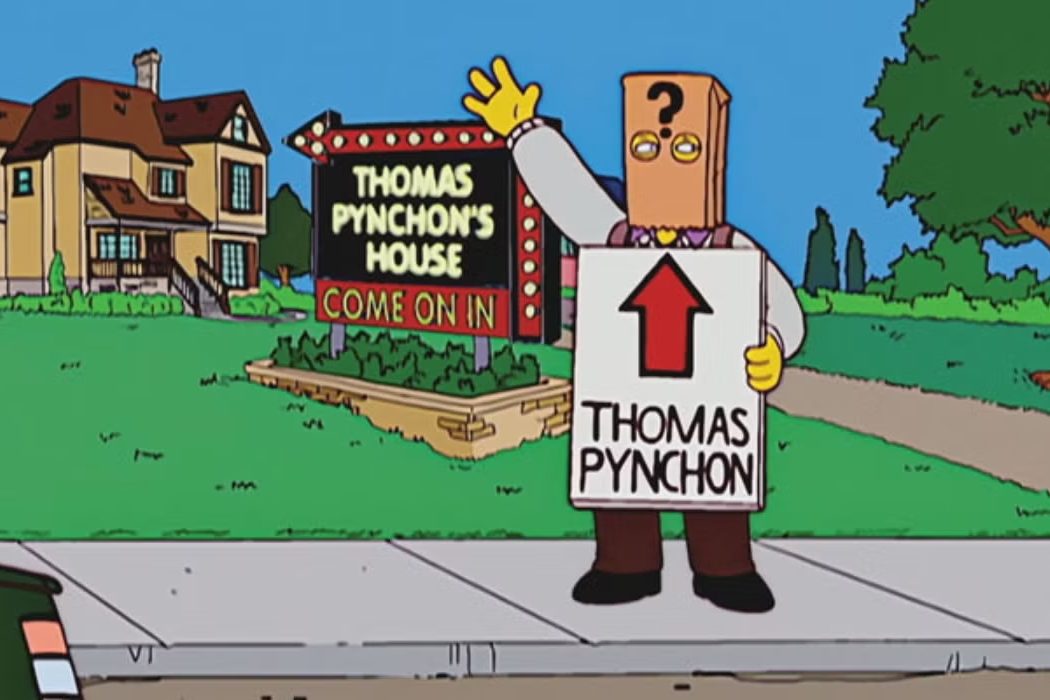

Much has been made in the Thomas Pynchon Reddit community — a crazed bunch — of the author’s rumored cameo appearance in Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2014 adaptation of his 2009 novel, Inherent Vice. Photos circulate in a frenzied online meta conspiracy: is he this old man? That guy in the hat? Famously reclusive, Pynchon has barely been photographed in real life. His only acting credit was when he voiced himself on The Simpsons, while his cartoon likeness appeared with a paper bag over its head. Pynchon revels in the oxymoron of the anonymous celebrity and his fans simply can’t get enough.

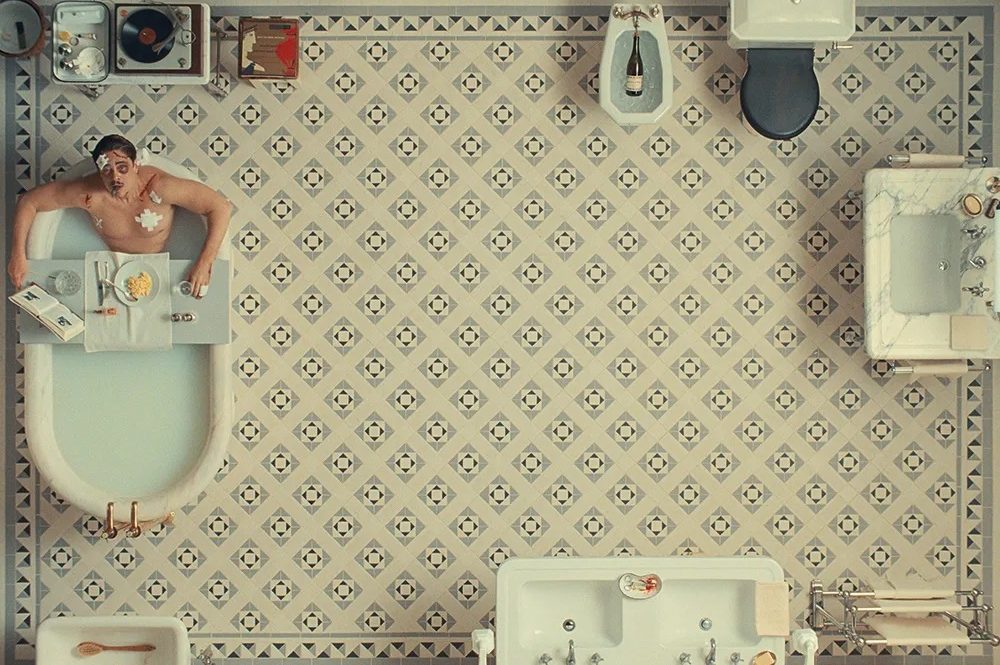

He found the right director to bring his work to the screen. Anderson’s own portfolio contains such enigmatic, head-scratching masterpieces as Magnolia (a plague of frogs and Tom Cruise as a sex guru), Punch Drunk Love (Adam Sandler and Emily Watson fall in love) and, oh boy, There Will Be Blood, a one-of-a-kind polyamorous marriage of Kubrick, Welles and John Huston that not only features a titanic Daniel Day-Lewis performance but asks penetrating questions about the American dream.

If Anderson’s Inherent Vice, which turns ten this year, has anything to say about the American dream, it is to mock its high-falutin’ nature, thereby proving the old adage that if you are going to tackle a subject, the best way of doing so is once as tragedy, then as farce. Certainly, Anderson was initially flabbergasted. His first reaction, when he read the spiraling and conspiratorial hippie crime novel, just before its publication, was to say “I’m never going to make this into a movie.” Like all Pynchon’s novels, the plot was too labyrinthine, too convoluted, too bewildering for the silver screen and its lay audience. It was simply unfilmable.

Yet Anderson is not a man to be daunted by such a challenge and, for better or worse, he made the movie. It remains Hollywood’s only attempt to tackle Pynchon’s Daedalian oeuvre, although exciting rumors are swirling that Anderson is currently working on bringing another novel, 1990’s Vineland, to a movie theater near you. Unfortunately, the first film’s comparative commercial failure — it grossed a mere $14.7 million — means that studios are unlikely to be lining up to make more Pynchon. But what is it about one of America’s greatest and most eccentric living authors — with an obsessive fascination with the movie industry, no less — that makes him so troublesome to film?

Both the novel and film of Inherent Vice revel in the shaggy-dog absurdity revolving around dope-fiend private investigator Larry “Doc” Sportello, who finds himself entangled in a web of plots involving the mysterious disappearances of his ex-girlfriend and a billionaire land-developer, the Aryan brotherhood, a drug-addled tenor sax player and an elusive organization known only as the Golden Fang. All of this is set in the fictional surf town of Gordita Beach as the psychedelic Sixties amble their way to a close. It might sound confusing, but it’s all part of the fun.

With his perm, outrageous mutton chops, and joint forever to hand, Doc is like Philip Marlowe reimagined, if Raymond Chandler had been an enthusiastic weed-smoker. He is beautifully played by Joaquin Phoenix, who excels in the art of the freakishly paranoid stoner stare. Phoenix is joined by a stellar cast of subversives and anti-subversives: Katherine Waterston as Doc’s “ex old lady,” the ephemeral Shasta Fay; Josh Brolin as hippie-hating lieutenant detective Christian “Bigfoot” Bjornsen; Reese Witherspoon as a sympathetic deputy DA and, best of all, Martin Short as a nefarious dentist and serial philanderer who also happens to be a coke-head puppet of the Golden Fang.

If it sounds unfathomably chaotic, Anderson’s genius is to turn it into a tautly executed period piece that simultaneously succeeds as a patchouli-infused vision of 1970 and an offbeat, loose-limbed crime caper, which adheres admirably closely to its source material. The groovy soundtrack sends us right back to an endearing period of “I can dig it” counterculture. Shadowy, malign capitalist entities causing trouble for hippie-dippie flakes who just wanna be left alone and smoke a doobie, man, is an underdog story most of us can get behind.

Anderson’s only major innovation is a welcome one: the soporific voice-over of Joanna Newsom’s Sortilège (a minor character in the book) guides the audience through all the wacky events and provides access to some of Doc’s more profound inner thoughts: “forget who — what was he working for anymore?” This technique also allows Pynchon’s notoriously protracted prose to infiltrate the screen and shine. The narration whirls delightfully and the film would be incomprehensible without it:

When Doc came in that night, it wasn’t just the usual hungry-doper thing — it was something else — and with Neptune moving at last out of the Scorpio death-trip and rising into the Sagittarian light of the higher mind — it was bound to be something love-related…

The dialogue, taken directly from the novel for the most part, sings and soars, such as when a British ex-showgirl, now in her forties, is described as “not so much English rose as English daffodil.” Alternatively, it riffs humorously off pop culture: “Like Godzilla sez to Mothra, man, ‘let’s go eat some place.’” That, and Anderson’s adherence to his baggy source material, is no mean feat.

Nonetheless, most of those unfamiliar with the book left cinemas baffled and perplexed. During a press conference at the film’s New York premiere, Anderson seemed irritated by one reporter’s observation that the film lodged “very funny moments” against “very dour” scenes. Clearly this was not the intention. But it’s true that the film is a more sober affair than the book, in both senses of the word. Joints punctuate the novel as much as commas, yet the film feels distinctly less trippy. Where were the pulsating hazy visuals? In retrospect, Inherent Vice should never have tried to compromise with mainstream cinemagoers. Give us swastika-tattooed biker-gang members camply duetting on Ethel Merman’s “You’re just in love” from Call Me Madam! True aficionados of Pynchonmania live for such entropic whimsy.

Pynchon is admittedly difficult to film. His novels are jam-packed with a whole host of interconnected characters and plot lines. What is near-impossible to convey on screen — particularly in the hands of an auteur — is the kaleidoscopic feel of his work. Yet Anderson has honorably proved that Pynchon is not, in fact, impossible to tackle in cinema. Sure, there were elements missing. The film lacks a certain jauntiness one associates with Pynchon’s lighter moments. But the curse of adaptation is that one necessarily limits an original. And, after all, the book hasn’t gone anywhere.

My greatest hope is that, whatever happens in the future, Anderson has opened the door to further cinematic incarnations of Pynchon’s work. Forget about the moribund Marvel Cinematic Universe; if we’re lucky, the Pynchon Cinematic Universe will baffle and beguile us all. Let’s have the singing and dancing mice of Gravity’s Rainbow or the pot-smoking George Washington from Mason & Dixon, please.

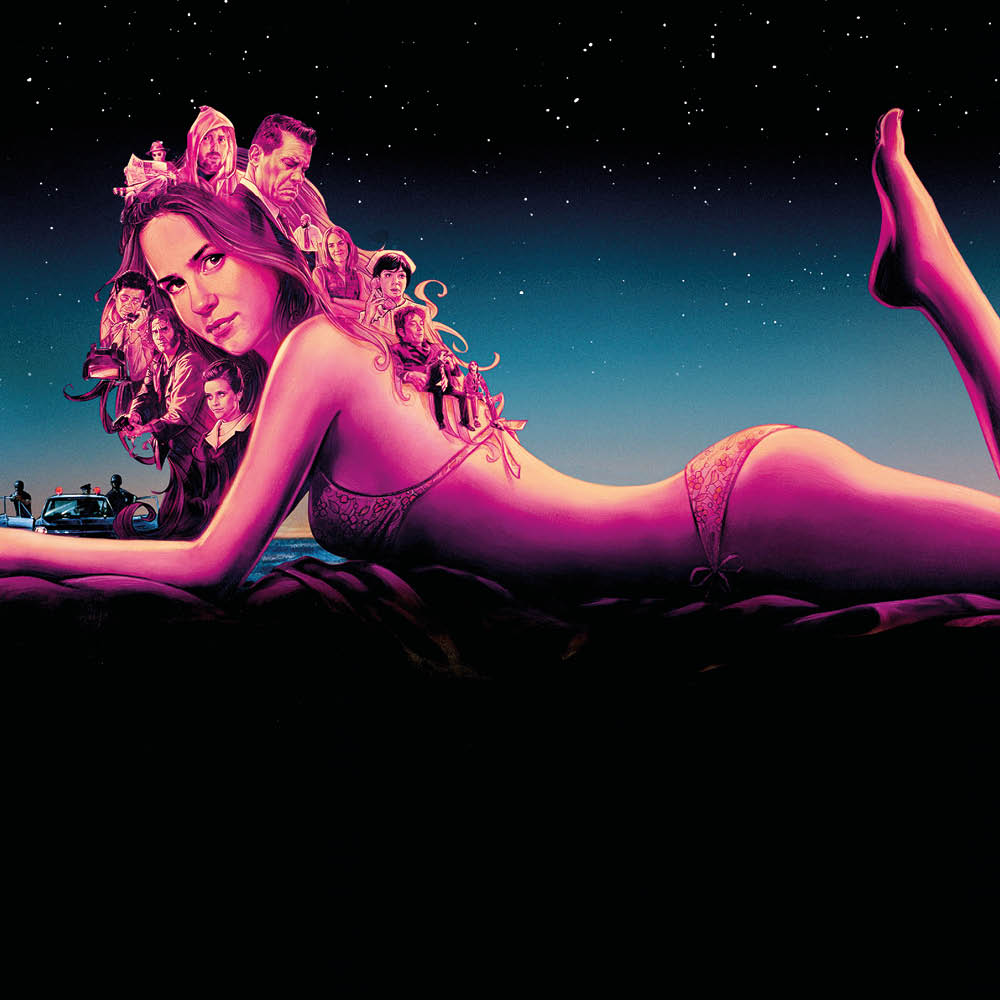

Who might lead this fantastical charge? Harmony Korine, with the bikini-clad criminality on offer in his neon-soaked portrayal of Florida, Spring Breakers, combined with the feral incoherence of his earlier work, Gummo, could be a contender, although his work is more nihilistic than Pynchon ever is. David Lynch likewise ticks the boxes of off- beat, serpentine, and downright bizarre plotlines. But the relatively unprolific Richard Kelly has to take the madhatter crown.

Best known for the evil giant rabbit insanity of Donnie Darko, it is Kelly’s greatest flop — Southland Tales — which makes him an ideal candidate for a Pynchon adaptation. The film is a darkly comic psychotropic bonanza about a vast conspiracy concerning the end of the world. Starring not only Sarah Michelle Gellar (as a porn star) and Justin Timberlake (as a mutilated soldier who performs drug-induced musical numbers) at the peak of their early Aughts fame, Southland Tales also boasts Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson’s finest performance as a paranoid actor going method with the LAPD. Despite having nothing overtly to do with Pynchon, it’s still the most Pynchonian film out there.

So yes, this is a call to arms. Directors, the world of Pynchon is your psychedelic, polychromatic oyster. Let’s get some grit into that particular cinematic pearl, shall we?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply