Martin Scorsese thinks Marvel films aren’t cinema. “The pictures are made to satisfy a specific set of demands, and they are designed as variations on a finite number of themes,” he wrote in a New York Times article in 2019, written after a wave of backlash from superhero fans and directors alike. Earlier that year, Marvel’s three-hour blockbuster Avengers: Endgame had garnered over $2.7 billion. For a while it was the highest-grossing film ever made. People turned up to see it in spandex catsuits. You couldn’t move for replica infinity stones. Some theaters, eager to fill the demand, screened the film over and over for seventy-two straight hours.

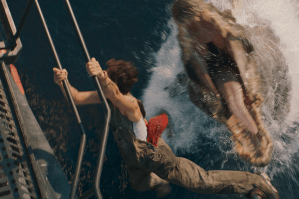

Actors start on the indie circuit and end up in front of green screens, wearing underpants outside of their clothes

Now everything’s coming up Scorsese. The Marvel strongmen have fallen from the sky and landed, cape-first, onto concrete. Last year’s The Marvels, a group outing of female superheroes, made a profit of only $47 million on its $200 million budget — the lowest box-office takeaway of any Marvel film. The film blog Deadline blames Disney+ streaming services. In its on-demand delivery of superhero “content,” it does away with most of the magic of going to the movies. Fair enough. But there are other dimensions to the decline.

I survey friends who like superhero films, only to find they’ve all gone off Marvel films. One says she hasn’t seen a Marvel film in nearly six years because the plots are too complicated. All of the heroes operate in the same universe: you have to have watched every Marvel release of the last decade to understand whatever they put out next. Another used to watch the films regularly but found that the different fight scenes started to merge into each other. Some pin the decline to the birth of Disney+ and others to the release of Endgame, which killed off several of the franchise’s most recognizable characters. “Too many movies and shows to keep track of,” explains another ex-fan.

The only person I can find who has actually seen The Marvels is my thirteen-year-old cousin. The film was only released in November but he has already forgotten most of its premise. He thinks the franchise’s villains have become weedy and uncharismatic, which makes the productions less watchable on the whole.

Marvel has its own cinematic universe and its own cinematic language. Viewers are getting sick of both. Writer Freddie DeBoer complains that the screenwriters too often undercut tension with identikit quips. Photography magazine Format ran a hit piece about Marvel’s color grading: the films are so desaturated that they look like “muddy concrete.” Cast and crew poke fun at the declining quality of the studio’s visual effects.

Take last year’s Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania. (There’s no denying it: the B-movie is the new A-movie. Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania sounds like something you might have sandwiched between some grainy newsreels and a gladiatorial epic, screened to a rowdy army of mid-century children. Only in 2023 could such invertebrate adventures have commanded a $200 million budget and an appearance from Michelle Pfeiffer). On Letterboxd, an online review platform frequented mainly by quippy under-thirty-five-year-olds, the release garnered endless mockery. “It took me thirty-one films,” says the top comment, “but I finally started to empathize with Scorsese.” “Do they know film is a visual medium,” said another review.

It used to be that convoluted sequels were reserved for a thespian underclass. Now everyone seems to have sold out. Actors start on the indie circuit and end up in front of green screens, wearing underpants outside of their clothes. Chloé Zhao, the Oscar-winning director of sprawling arthouse flick Nomadland, was poached in 2021 to direct Marvel’s The Eternals. The other day I was disheartened to see Dakota Johnson front-and-center on the poster for Madame Web, a new Marvel film related vaguely to Spiderman. Your grandmother was in The Birds, I thought. Is nothing sacred?

Perhaps Marvel, in all of its demands and themes, misreads the true logic of Hollywood. While The Marvels came with strong girl-power branding, most of the people who bought tickets for the film, according to Deadline, were male. The female superhero fans I spoke to all fall towards the political left, but they still seemed more interested in Tom Hiddleston’s weaselly grin than representation. Sex sells. Barbie made $1 billion at the box office thanks to a script that combined elements of musical and screwball comedy. Both genres came into existence to entertain mostly female audiences and did so, with phenomenal success, for around twenty years. Women want more than a sex-substituted version of the same thing they’ve been getting for the last fifteen.

We can draw a comparison here to the death of the studios of yore. Marvel is a bit like Louis B. Mayer’s MGM — the difference is that the former is tremendously inefficient, outsources almost all filmmaking responsibilities to independent contractors, and can’t birth a star to save its life. Marvel has swallowed so much of the film landscape and assimilated so many storylines into a single universe that it is fit to explode. It doesn’t need an antitrust lawsuit as much as it needs a round of Ozempic.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.

Leave a Reply