Jane Fonda’s telephone manner was nothing if not imperious. “This is Jane Fonda herself,” she said one spring morning in 1982, in a transatlantic call from Hollywood to Cannes. The German film director Rainer Werner Fassbinder was so tickled that for days afterwards he took to answering every phone call in English with: “This is Fassbinder himself.”

‘Fassbinder wanted to be Marilyn Monroe. He wanted to walk down a staircase wearing feathers and a gown’

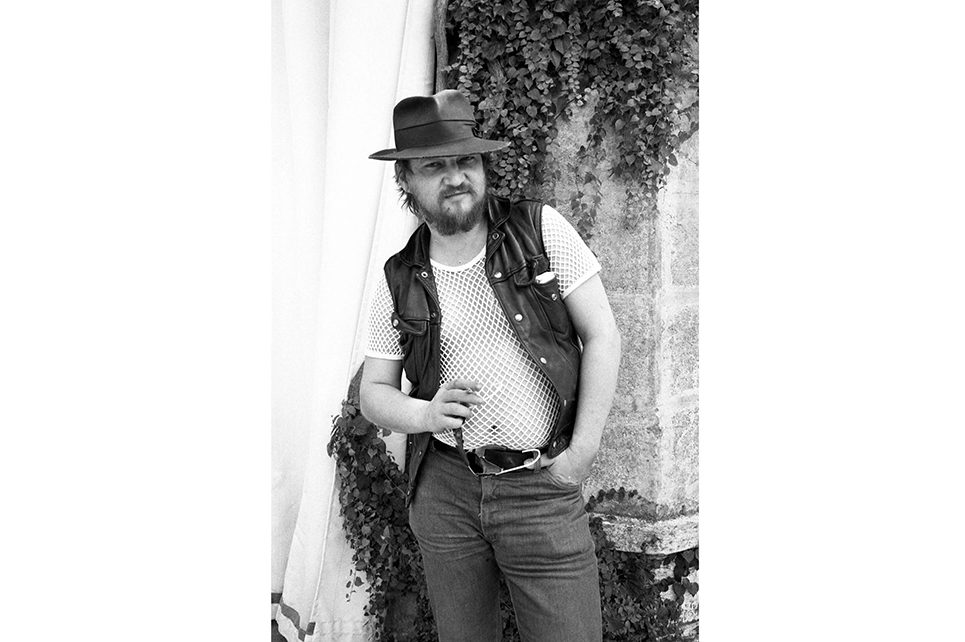

It was the meeting of opposites. She was Hollywood royalty, Henry’s daughter, sexy star of Barbarella and double Oscar winner, poised to release the first of her series of workout videos that would in the next thirteen years sell 17 million copies. By contrast, Fassbinder probably didn’t even own a pair of leg-warmers. He was, as Ian Penman reports in this slender love letter to his oversized, cocaine-addled hero, “the unregenerate opposite of a certain micro-fascist 1980s gym/body culture: 60-80 cigs a day; big white steins of Bavarian beer; big plates of his favorite calorific German food.” Fassbinder was referred to in German tabloids as “RWF,” as if to shrink the legend of this mythic ogre into manageable proportions. He was routinely described, Penman tells us, as “a slob, a barbarian, a punk anarchist queer… a monster of sexual indulgence and shock horror left-wing quotes and bad drug rumors.”

He died aged thirty-seven, having made forty-three films, not just directing, but writing, producing, set-designing, editing, choosing music, photographing them — and starring in more than a few. Had he lived on he might have been more celebrated — outdoing on screen and in life even such monomaniac German director contemporaries as Werner Herzog and Wim Wenders. But he didn’t and isn’t: hence the need for Penman’s lovely tribute.

At the time, Fassbinder wanted Fonda to star in his forty-fourth film, tentatively called Rosa L., about the socialist firebrand Rosa Luxembourg, murdered in 1919, her body thrown into Berlin’s Landwehr canal. It was a brilliant idea. Fonda had been nicknamed “Hanoi Jane” after being photographed with North Vietnamese troops on an anti-aircraft gun that would have been used to shoot down American planes (as I write, the probably non-ironic “Jane Fonda American Traitor Bitch” lapel badge sits on my desk) and so had both the radical chic and Hollywood posh to animate his project.

Fonda could have joined RWF’s roster of muses — Hannah Schygulla, his ex-wife Ingrid Caven, Rosel Zech, Barbara Sukowa and Margit Carstensen. These women played the titular heroines of his greatest movies — The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, Effi Briest, Lola, The Longing of Veronika Voss and The Marriage of Maria Braun, each one a stylish depiction of German psychopathology made on a shoestring budget.

It wasn’t to be. A month after the Fonda phone call, Fassbinder went to bed. He called a friend to say he had flushed his drugs down the toilet. Apart, that is, from the line of coke that killed him. He was found with a cigarette between his lips, blood trickling from one nostril. Notes for Rosa L. and other projects were found nearby.

“Did he in fact commit suicide, by trying to live up to an exaggerated version of himself at large in all the mirrors of the world?” asks Penman. It’s a theory. Another is weirder. He died, friends pointed out, at the same age as Marilyn Monroe, and in the same way. “Fassbinder wanted to be Marilyn Monroe,” said one. “He wanted to walk down a staircase wearing feathers and a gown.” If he couldn’t live like Marilyn, perhaps then he could die like her. That night in London, Penman took heroin for the first time in a night club and the following morning went to work and wrote his hero’s obituary.

Penman, one of the critical gunslingers who, along with Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons, made the New Musical Express of that era essential reading, was obsessed with the director. He has seen Veronika Voss four times. “Why was I so drawn to Fassbinder?” he asks. One reason was that the monstrous omnivore refused to allow culture to be compartmentalized into what Penman calls “high/low/improper” boxes. The other, more unlikely still, is that he was a role model for the young critic, a wurst brat who made the supposed badass punks of alternative music seem mimsy by comparison.

But could Fassbinder — whose last movie Querelle was based on Jean Genet’s tale of a sexy Belgian sailor sucked into a vortex of murder, BDSM and lots of other putatively shocking hokum — retain that allure for Penman forty years on? Researching this book, Penman reviewed his hero’s oeuvre. Some, such as the fifteen-hour TV series of Weimar crime, Berlin Alexanderplatz, he admits proved hard going. Petra von Kant, which I adore for its bonkers frocks and painful evisceration of the eponymous fashion designer’s desire for Hanna Schygulla’s saucy ingenue, doesn’t seem to have engaged Penman as much as it does me.

But, thanks to this book, other works leap from relative obscurity, among them the 1974 sci-fi TV drama World on a Wire. This pre-empted The Matrix in imagining that the world is a simulation. Cybernetics whizzes have created an artificial world with more than 9,000 “identity units” who live as human beings, unaware that their world is just a simulation and that their identities are scripted by techno geeks. Despite tragic sideburns and flares, it seems oddly clairvoyant. Penman even comes up with an equation to capture Fassbinder’s prophetic power: “Consumer Society + Terror State x Digital Info + Surveillance = The Future.” If so, Fassbinder wasn’t far wrong.

And then there’s In a Year of 13 Moons (1978), made in response to the suicide of his lover Armin Meier. It’s the improbably heartbreaking drama of Elvira, a trans woman, formerly a butch butcher, who underwent a sex change for the romantic interest who has since humiliated and abandoned her, leaving her regretting her lifestyle choices.

Most of all there’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974), about the unlikely romance between Emmi, an elderly German woman, and Ali, a Moroccan Gastarbeiter, in which Fassbinder plays Emmi’s loathsome son-in-law, channeling the ugly racism of Emmi’s former friends and colleagues. Love, in Fassbinder, is always difficult, often outrageous to straitlaced bigots, but nowhere else in his movies quite as sweet as here.

Fassbinder may have not left a good-looking corpse, but he did leave us with something else: a handful of still beguiling, visually gorgeous films. Just a shame that Jane Fonda didn’t get to star in one of them.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.