In 1587, the Mughal Emperor Akbar, himself illiterate but with grand vision and even greater ambition, commanded his courtier Abu’l-Fazl to write an official history of his reign and dynasty. An order went around Akbar’s court that anyone who was “gifted with the talent for writing history” should put pen to paper and record the events that had shaped their times. Unusually for a male-dominated society, this included the emperor’s aunt. The sixty-four-year-old Princess Gulbadan was well placed to provide a first-hand description of the creation and consolidation of the Mughal empire, for she was the beloved daughter of the Emperor Babur, who founded the dynasty, and the half-sister of Akbar’s father, Humayun. Yet when her account was finally translated into English at the beginning of the twentieth century, even the publisher called it “a little thing.” Thanks to Ruby Lal’s Vagabond Princess: The Great Adventures of Gulbadan, we now know it to be of immense value. The only surviving prose from a woman of that time, it is lively and uniquely revealing.

‘After the blinding, His Majesty the Emperor…’ — and then what? We’ll never know for sure

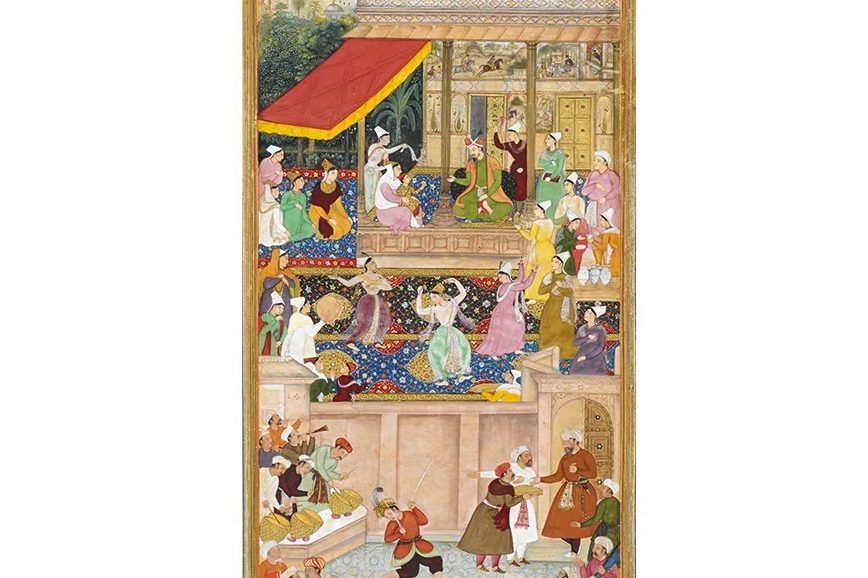

Gulbadan, whose name means “body like a rose,” was born in 1523 in the Bala Hisar, the great fort of Kabul, at a time when Babur was still fighting to create his empire. When she was six, Babur ordered his wives, children and female relatives to leave Kabul and join him in Hindustan. It was a slow, grand, nine-month procession, covering less than 100 miles a month and involved crossing the Kyber Pass and River Indus. Gulbadan never forgot the adventure, but more than the journey itself, it is the snapshots of the court and glimpses of daily life in the female quarters that stand out in her account. When Babur visits his women — most memorably in the gardens he loved — Gulbadan captures the excitement, joy and sense of completeness everyone experiences when the emperor is present. But when he is away on campaign, there is great anxiety among the women, who risk becoming war booty if he is defeated.

The British Library holds the only known copy of Gulbadan’s memoir. Through its eighty-three thin folios, each page filled with fifteen lines of black cursive script, this powerful, observant, long-lived and eloquent woman speaks to us. But not all she had to say has survived. The manuscript comes to an abrupt end when Humayun orders his rebellious brother, Kamran, to be blinded. Gulbadan wrote that “the order was executed at once. After the blinding, His Majesty the Emperor…” — and then what? We shall never know for sure because the following pages have been lost. But Lal, professor of South Asian studies at Emory University in Atlanta, has done a brilliant job of turning to other sources, including Abu’l-Fazl’s official history, the Akbarnama, and imagining what might have been recorded. She also explains why it was possibly suppressed.

In 1576, in Fatehpur-Sikri, Gulbadan, aged fifty-two, asked Akbar’s permission to go on pilgrimage to Mecca. There were reasons apart from religious ones why she might have wanted to make the journey, including escape from the seclusion of women inside the Fatehpur harem. Akbar gave his blessing — and not just to please his aunt. He recognized the political value of an imperial Mughal party making the hajj across waters controlled by the Portuguese and in a region of Arabia managed by the Ottoman sultan who had styled himself protector of the holy places. Politics would dog the journey, with the Portuguese reluctant to grant permission for the Mughals to sail from Surat and, during the four years they stayed in Arabia, Murad III issuing several decrees to have them evicted. He was furious that they had been distributing alms — something that was seen as the sultan’s prerogative.

In March 1580, Gulbadan and her entourage left Arabia in a hurry, ahead of the sultan’s latest decree, and sailed east towards the Indian Ocean. The following year, Akbar put an end to the pilgrim caravan from Mughal lands and withheld his donation to the holy cities. This was no small amount — half a million rupees had been sent the previous year. Now, Akbar explained to the sheriff of Mecca, the money was needed for his campaign in Kabul, although in truth the withholding of funds was a rebuke to the Ottomans for having made difficulties for his aunt.

Perhaps her description of what happened in Arabia made Gulbadan’s account too political, and it was for this reason that the last pages of her manuscript were suppressed. Whatever the case, her voice humanises some of the great characters of the time and provides a rare first-hand picture of life during the dramatic rise of the Mughals.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply