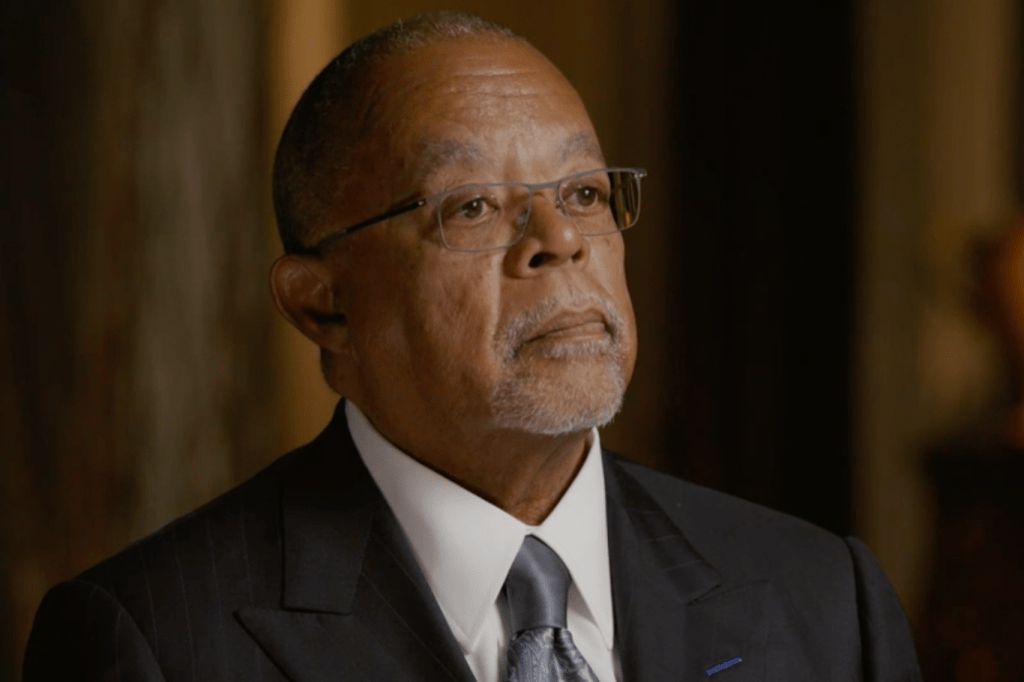

In PBS’s Finding Your Roots, celebrity guests learn about their genealogies from the Harvard historian Henry Louis Gates. The guest on February 9 was the Lebanese-American actor Tony Shalhoub. The episode made several false or misleading statements that downplayed what historians now call the ‘30-year genocide’ – the mass killings perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire against Christians from the 1890s through the 1910s.

In his academic specialty, African and African American studies, Gates is acutely aware of violence and discrimination. Episodes of Finding Your Roots often dwell on the legacy of slavery for black and white Americans alike. Yet Gates never once uttered the words ‘genocide’, ‘extermination’ or even ‘ethnic cleansing’ to describe Ottoman atrocities.

Shalhoub’s paternal grandfather, Gates says, ‘found himself in the army, likely serving in what was called a labor battalion’. Justifying the policy of conscription, Gates told Shalhoub, ‘Remember, how long I said that empire existed? Four hundred years. It was about to come to an end, man… The rubber hit the road.’

This was not standard military conscription. It was a manifestation of a program of concealed genocide. Labor battalions used only the people that the Ottomans saw as expendable: Christians. Their death rates were staggering. Elias Venezis, a Greek survivor, wrote that only 23 out of the 3,000 men in his labor battalion survived the war.

Next, Gates talks about the hardship that befell Shalhoub’s grandmother:

‘In March of 1915, a locust plague descended on the Middle East, destroying more than 60 percent of Mount Lebanon’s summer crops… Soon, the region was ravaged by famine and disease.’

Yet the famine had man-made causes. From 1915 to 1918, Mount Lebanon was under the bloody fist of Djemal Pasha, one of the infamous ‘Three Pashas’ who oversaw the Ottoman Empire’s uniquely genocidal involvement in World War One. His brutality and cruelty were so notorious that he was known as ‘Djemal the Butcher’. During the War, Djemal applied the Ottomans’ divide-and-rule strategy to the Levant. The Maronite Christian population had historic ties to the French and the British. The Ottoman despots feared that the Maronites would sooner aid France and Britain than continue to endure their abusive rule. In a characteristic act of Ottoman inhumanity, Djemal imposed a land blockade on the Mount Lebanon region to starve it into submission. Recent articles have identified the blockade as the leading cause of the devastating famine, which killed as much as half of the population of Mount Lebanon.

The blurring of the Ottomans’ genocidal record continued:

‘[Shalhoub’s great-grandfather] died in 1895, in a region of the Ottoman Empire which was then part of Armenia. At the time, Armenian nationalists were pressing for political reforms, and the Ottoman state decided to make an example of them. An estimated 150,000 people died in massacres that made international headlines.’

Though he does not name them, Gates is speaking of the Hamidian massacres of 1894-1897, during which as many as 400,000 Armenians and other Christians were killed. Gates wrongly identified these killings as the politically motivated repression of Armenians. Instead, these were the overtures of the methodical slow-moving genocide of Armenians and other Christian minorities that accelerated during World War One.

In the Hamidian massacres, Ottoman authorities incited mob violence against Christians. Turkish historian Taner Akçam, who has spent his career fighting against Armenian genocide denial, faults Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s policy of pan-Islamism for causing the violence against Christians. ‘The attacks,’ Akçam writes, ‘had the nature of pogroms’ against Jews. ‘The state unleashed its attacks on the slightest provocation, calculating that this would bind Muslims more closely to the empire… The goal was for Muslims to look upon attacks against Christians as the fulfillment of a religious duty.’

In the authoritative Cambridge History of Christianity, Anthony O’Mahony writes that the Hamidian massacres ‘were not, however, limited to the Armenians, and the Syrian Christians of the region also suffered terrible losses. Figures vary, but one contemporary account puts the number of Syrian dead at 25,000, including 3,000 burnt alive in the cathedral of Edessa in which they had taken shelter.’

Strangest of all, Gates discredits a contemporary report about the killing of Shalhoub’s grandfather. Shalhoub reads a harrowing passage from a period newspaper clipping: ‘He was crucified, being nailed hand and foot to a cross and left to suffer many hours before being finally dispatched by a lance thrust. Particulars reached his son in Appleton by letter from a relative who escaped.’

Shalhoub is astonished and repeatedly asks if the story of the crucifixion was true. Gates’s response is stunning.

‘Well, the article was written during the era of yellow journalism, where newspapers often sensationalized or exaggerated stories to improve circulation, right? And at the time, there was a major bias in American newspapers against the Ottomans because they were Muslim. So it’s possible the story was exaggerated.’

Gates ignores the fact that the article cited a letter to Shalhoub’s grandfather from a survivor of the massacres as its source. In the face of the evidence, a genocidal regime becomes the victim of Western journalistic bias.

Gates describes the murder of Shalhoub’s ancestor as another one of those ‘unimaginably horrible things that people have done to our ancestors’. But this was not just a random barbarity. It was part of an attempted extermination, orchestrated over the span of three decades.

Gates may have been misinformed by PBS’s researchers. Perhaps they neglected to read the established scholarship or even look at Wikipedia. Perhaps the network edited the episode for length. PBS declined to comment for this story. But Gates, who signed a petition condemning Armenian genocide denial in 1999, ought to have known better.