Why are there no paintings in Star Wars movies?

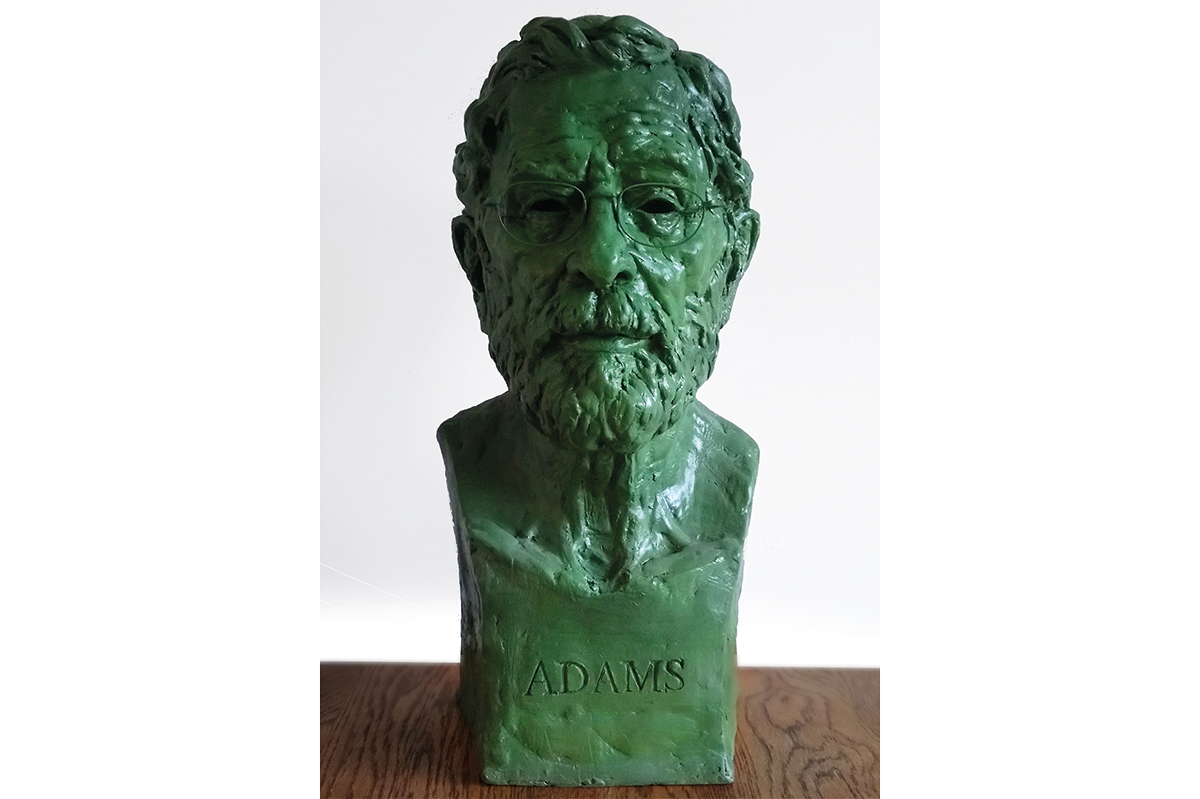

The question occurred to me recently, rewatching The Rise of Skywalker. I’m old enough to recall seeing A New Hope in a drive-in in summer 1977, as well as the infamous Star Wars Holiday Special on television in 1978. Over time, my interest in Star Wars has shifted into something akin to nostalgia, so it may not be surprising that this question never struck me before. What is surprising, however, given their glaring omission from the films, is that the man who created the Star Wars universe happens to be a major collector of art — including paintings — and is due to open the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles by 2025.

Certainly, sculptures appear in the Star Wars films. For example, massive statues on plinths appear to guard the entrance to Theed Palace on Naboo in The

Phantom Menace. Theed’s interiors, which were shot at the grand, Baroque-era Caserta Royal Palace outside of Naples, occasionally give glimpses of the real building’s sculptural decoration, such as marble statuary or carved bas-reliefs. In the origin film Solo (2018), statuettes and other objets are displayed scattered about on illuminated stands in gangster Dryden Vos’s space yacht, the First Light. These demonstrate the character’s greedy acquisitiveness, showy taste and tendency to violence, but they also serve as “Easter eggs” for hardcore fans, who know the origins of these objects from sources outside the films themselves.

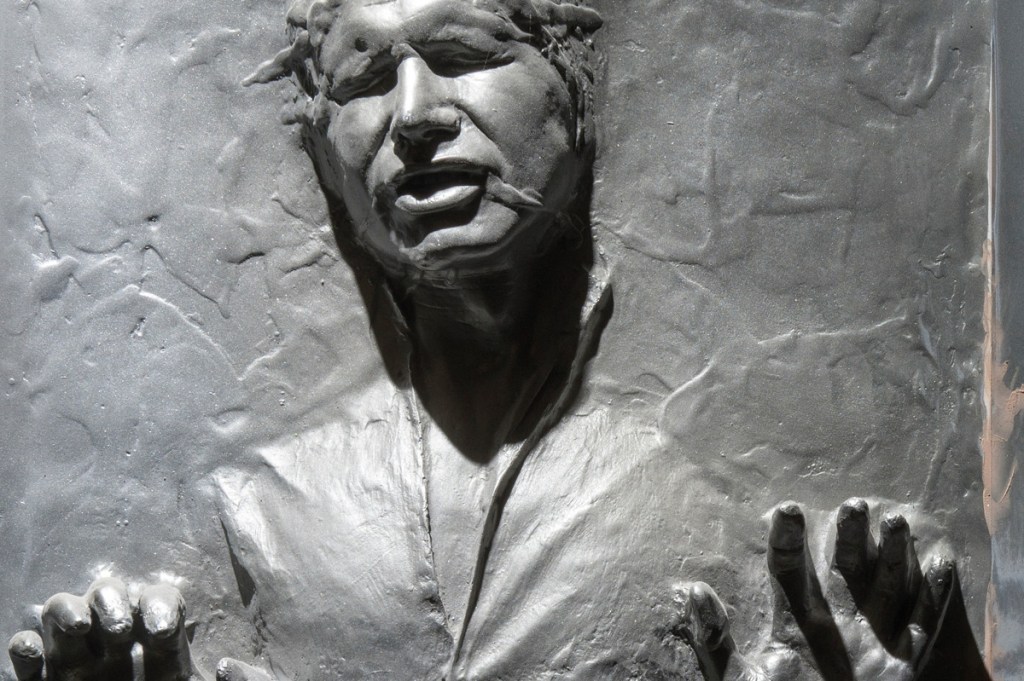

Arguably the most important piece of sculpture in all of Star Wars, and the subject of possibly the only scripted reference to visual art in any of the films, isn’t really sculpture at all. In Return of the Jedi, Jabba the Hutt refuses to release Han Solo, who has been frozen in carbonite and is displayed hanging on the wall in Jabba’s palace. “I will not give up my favorite decoration,” Jabba comments, in response to a hologram message sent by Luke Skywalker. “I like Captain Solo where he is.” Of course, Jabba’s decoration is not really a statue, but something more akin to displaying the head of one’s defeated enemy on a pike.

In many of the Star Wars films, drawings and illustrations serve as MacGuffins to advance the story. The most famous example of this is the set of plans for the original Death Star. The schematic drawings for the moon-sized weapon appear on screen and fuel the plots of both Rogue One and A New Hope. Meanwhile, maps of secret locations are used to similar effect in Attack of the Clones, The Force Awakens and The Rise of Skywalker.

While these images are utilitarian rather than purely artistic, they demonstrate the ability of the residents of this galaxy to conceive, execute and understand abstracted, two-dimensional representations of real-world, three-dimensional objects.

While I freely admit the possibility that a more eagle-eyed reader will be able to point to a painting that slipped my attention and appeared briefly in one or more of the big-screen Star Wars films, there’s no question that paintings have never been important to the stories. They are not talked about, reflected upon or even alluded to, at least not in the ways that we usually engage with this form of art. Given the presence of many other types of art in Star Wars movies, how can we explain this?

Stephen Kent is the author of How the Force Can Fix the World: Lessons on Life, Liberty, and Happiness from a Galaxy Far, Far Away, and hosted the Beltway Banthas podcast from 2016-22. As a political commentator and PR strategist who has witnessed the breakdown in basic civility in recent years, Kent suggests that a way for society to begin again is to use the Force. The book views such matters as empathy, hope and balance in contemporary politics through the lens of the Star Wars universe.

Speaking with Kent, I noted that many of the settings for the Star Wars films were either bellicose (battlefields, military bases, warships), or inhospitable (deserts, swamps, tundra.) Therefore, it might be reasonable not to expect paintings in such environments. At the same time, there are also plenty of relatively stable, even luxurious, places shown on screen, where paintings would look perfectly at home.

“It’s correct to think of the original Star Wars trilogy as a future that is slightly dystopic and blended with the Stone Age,” Kent points out. “The aesthetic of those films is meant to feel hollowed out, rusted and worn down. The age of the Empire was not good for self-expression or prosperity, and I suppose we’re meant to conclude that with the collapse of the decadent Republic, so too came a collapse in the beauty of the galaxy.”

The small-screen portrayal of the Star Wars universe isn’t much different. “Even in the new live-action TV installments such as Andor and The Mandalorian, nothing,” Kent notes. “Senator Mon Mothma gets a lot of screen time in her elaborate apartment on Coruscant, the cultural capital of the galaxy, and it is completely devoid of wall art that is recognizable to audiences. Her rebel collaborator, Luthen, runs an antique shop but even that is confined to armor, weapons, jewelry and tools; there are a few broken-up old hieroglyphs.”

“The most art you’ll see in Star Wars during the Empire,” Kent continues, “is in the animated series Star Wars Rebels, which follows a band of rebels causing trouble for Grand Admiral Thrawn. The show digs in on how dissidents use art to communicate and preserve their cultures, which the Empire is actively trying to demolish. One character does graffiti and street art to recruit for the cause. Then Thrawn uses his personal love of art to study the cultures he is conquering, because he views art as the purest expression of who a people are. But Thrawn is from another part of the galaxy, far away from the star system that Star Wars is happening in. He’s sort of a visitor to this corner of the universe, and so it makes you wonder why he is the only person who seems to appreciate artwork.”

When it comes to the on-screen universe, then, the painting aficionado is mostly out of luck. “It’s like Star Wars’s many cultures jumped straight from cave wall art to hologram technology with nothing in between,” Kent observes. Perhaps there, in that mixing of culture and technology, we might find an answer to the question at hand, based on George Lucas’s own views on art.

In a 1975 interview for the documentary The Men Who Made the Comics, a young George Lucas, who was making the very first Star Wars film, said that his understanding of art was primarily influenced by anthropology.

“My take on art is more culturally oriented,” he explained. “And I look at art as a way of judging a culture, and understanding not really what it looked like or anything, but what the people were thinking and what the people were feeling, at a particular time.”

Nearly forty years later, in a 2012 interview with former senator Bill Bradley on Sirius XM, Lucas presented an expanded point of view of his understanding of the nature of art. “Every art form and every artist is struggling against technology. Because art is technology. It’s the one thing that you can do, that’s using technology to communicate emotions from one human being to another human being. And that’s the art of it, whether you’re telling stories, you’re doing plays, you’re doing music, you’re writing books, you’re painting pictures. It’s all about the technology.”

I’m not quite sure Lucas’s earlier observation is accurate — one could hardly tell what most people in eighteenth-century France were thinking and feeling by looking at the work of, say, Fragonard. And while Lucas has a point, with respect to art being a form of technology used for communication, this seems a rather cold way to look at something that, in its greatest expression, transcends a purely emotional response. However, cultural commentator Camille Paglia would appear to agree with Lucas’s assessments.

“No one has closed the gap between art and technology,” Paglia maintains, “more successfully than George Lucas.” Paglia, who has often referred to George Lucas as the greatest artist of our time, concluded her 2012 book Glittering Images: A Journey Through Art from Egypt to Star Wars with a paean to Revenge of the Sith, the last Star Wars film to have been directed by Lucas himself.

The conclusion of Revenge brings about the final transformation of Anakin Skywalker into Darth Vader, through a particularly violent and morally ambiguous battle with his erstwhile master, Obi-Wan Kenobi. “Nothing I saw in the visual arts of the past thirty years,” Paglia said, “was as daring, beautiful and emotionally compelling as the spectacular volcano-planet climax of Lucas’s Revenge of the Sith.” Paglia saw Lucas’s realization of this scene as deriving in part from Dante’s Inferno, which is fair enough, but also argued that it bears the influence of artists such as Jackson Pollock. I find this assertion more difficult to perceive, unless one sees blobs of computer-generated lava as proof of Lucas’s intentionally referencing Abstract Expressionist painting in his own work.

Perhaps the unsatisfying answer to the question posed at the outset of this piece is simply: “They forgot.” However, short of eliciting answers from Lucas or other filmmakers and production designers, it’s probably the best rational explanation we have. This is not to say, however, that painting has no relevance to Star Wars on the big screen: quite the contrary, in fact.

Through his paintings depicting the Star Wars galaxy, artist Ralph McQuarrie helped Lucas realize his ideas on film. Although McQuarrie, who was a commercial artist and illustrator, only worked on the first three movies released, his art had a tremendous influence on Star Wars from the very beginning. McQuarrie’s images were so appealing that Lucas used them to persuade studio executives to back his projects and would often recreate their sightlines and angles once filming began.

What’s more, from the very first film, McQuarrie and other artists created matte paintings that were used for many of the location backgrounds on screen. These were then combined with green screen projection, models, miniatures and sound effects to create believable environments in a time before fully digital realizations were possible. Later, as Lucas’s own special-effects company, Industrial Light and Magic, digitized the process, its digital artists continued to refer to McQuarrie’s aesthetic.

Without McQuarrie’s paintings, we would not have beloved and immediately recognizable characters such as R2-D2, C-3PO, or Chewbacca; visualizations of the Millennium Falcon, Hoth and even Imperial Stormtroopers can all be found in his paintings. Thanks to McQuarrie, Darth Vader gained the breathing apparatus whose rasping mechanics announce his arrival even before he appears on screen, to the terror of the other characters and indeed of the audience. Filmmakers working on Star Wars projects continue to draw on the paintings McQuarrie created as inspiration more than a decade after his death.

Perhaps ironically then, for a franchise that has avoided putting objects discernible as paintings on screen, paintings have had a tremendous impact on the realization of the entire Star Wars galaxy itself. All the Star Wars films are, in fact, filled with paintings of one kind or another, whether created by a physical or a virtual paintbrush. There may not be any individual canvases hanging in the Cloud City dining room when Darth Vader comes to call, but Cloud City and Vader himself look the way they do because of paintings created in order to bring such moments to life on film.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2023 World edition.