Milton Glaser was among the most celebrated graphic designers in the world, honored with one-man shows at such glittering institutions as the Museum of Modern Art and the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum. Glaser was the first graphic designer to receive the National Medal of the Arts award. His “I ♥ New York” logo has been emulated everywhere, and his Push Pin Studios set the standard for graphic design outfits around the world, likely creating more theater posters and magazine covers than any other in New York.

But when Glaser pitched one of his “dotty landscape paintings” to the 2017 Metropolitan Transit Authority’s (MTA) call for artists, its Art & Design judges turned him down. Glaser took the rejection in his stride. After all, he had already created artwork for the Astor Place station, “Untitled,” in 1986 — a set of geometric porcelain-enamel panels which riffed on the adjoining Grueby faience plaques that paid homage to the Astor family’s main source of income: the beaver.

And from time to time, according to Dan Bates, the longtime manager of Glaser’s studio, before New York’s most famous graphic designer died at the age of ninety-one in 2020, either Glaser or one of his staff would personally stop by the station and check on “Untitled.” “I recall it being in very shabby condition,” Bates says. “As with most things in the city, it has an element of grit to it. I’m not sure it would have necessarily stood out as problematic, but [it was] emblematic of the history of the station — and the city.”

These days, the subway’s artistic legacy runs as deep as its subterranean stations — from the terra-cotta signs designed by the system’s original architects, George Lewis Heins and Christopher Grant LaFarge, to the mosaics of Jack Beal in Times Square to the faceted glass of Barbara Ellmann way out on Van Siclen Avenue in Brooklyn. all of which stand open and unguarded for the public’s viewing pleasure. MTA Arts & Design, a public-private partnership between the transit authority, state government and public art foundations, now manages the most diverse collections of public art in the world, with more than 350 works by world famous, mid-career and emerging artists.

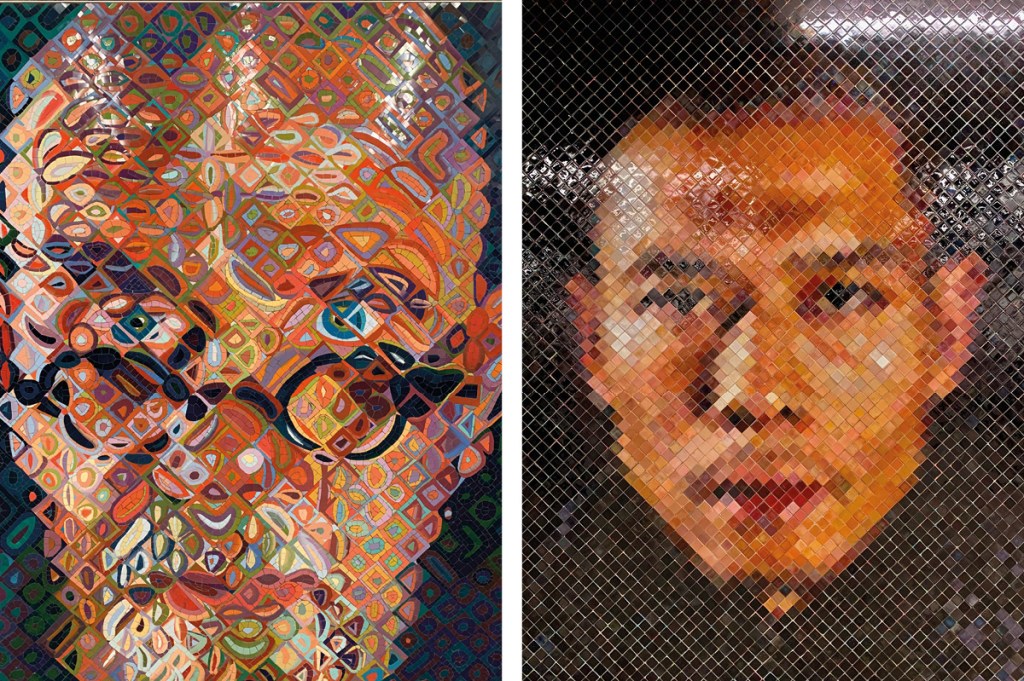

Lately, MTA Arts & Design has gone on a bit of a spending spree for subway artwork, particularly for the long-touted extension between Penn Station at 34th Street and Grand Central at 42nd Street. In May 2022, the agency revealed Nick Cave’s “Each One, Every One, Equal All,” a mosaic of the artist’s brightly colored wearable works across nearly 4,600 square feet — the largest such project completed to date in the subway system; Yayo Kusama’s “A Message of Love, Directly from My Heart unto the Universe,” part of Kusama’s “My Eternal Soul” series; Kiki Smith’s “River Light,” “The Water’s Way,” “The Presence,” “The Spring,” and “The Sound,” her ode to the East River; Jordan Bruner’s “The Grand Wander” and Paul Pfeiffer’s work, “Still Life,” which pays homage to the iconic New York City street performer “Da Gold Man” with large-scale photographs installed in double-sided light boxes. Arts & Design will not disclose how much it paid these artists for each commission (80 to 90 percent of the cost goes to fabrication), but a typical Cave Soundsuit goes for $189,000 and a Kusama can go for millions.

In addition to collecting, the MTA’s $55 billion remit also ensures that the century-old transportation network’s existing decorative elements are restored and renewed. Yet several of the uptown Heins & LaFarge terra cotta signs at the original twenty-eight stations are chipped and defaced, while the mosaics of the subway’s second architect, Squire Vickers, across the boroughs need a good cleaning. Glaser’s “Untitled” at Astor Square has been extensively scratched with names and random words and some faceted glass works in the outer boroughs have been broken and boarded up. With this new work going up, how is the MTA preserving the old — including the spinal column of the program made up of the works of such famous artists as Roy Lichtenstein, William Wegman, Sol LeWitt and Nancy Spiro, which have been in the subways for twenty years or more?

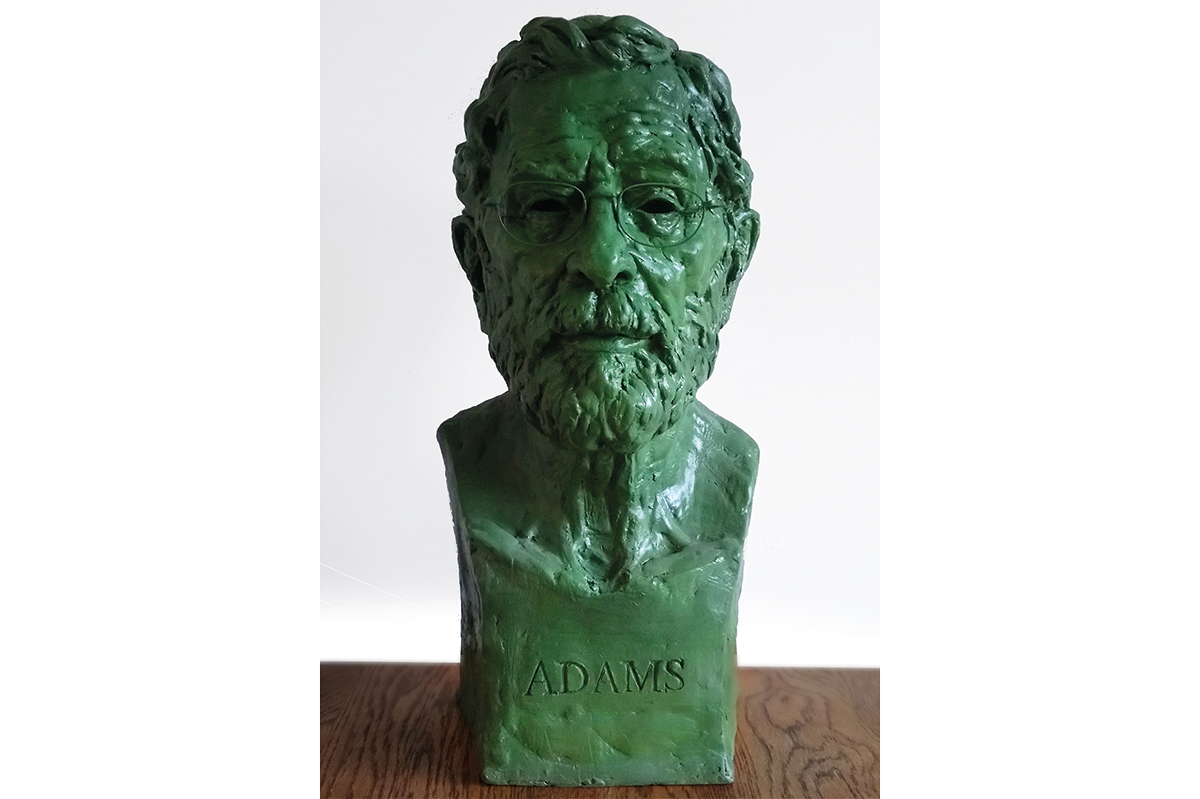

“When some of the early works were installed in the 1980s and 90s, the material that was chosen was not very durable and it became obvious that it was not going to hold up,” says Sandra Bloodworth, the longtime director of the MTA Art & Design Program, on a Zoom call from her office in New York. “Milton’s [“Untitled”] was one of the first to ever go up — there had been really no arts program in the subway before — and it was done on porcelain enamel, which can be touched up from time to time, but any permanent solution would require a re-creation,” she explained. “Early on in the program, I made the case for mosaics because everywhere we looked, the mosaics were in mint condition, while we were rescuing a lot of the other work.”

During the 1970s and 80s — the pre-Giuliani years — when New York was the “gritty and nonconforming” place for which some Lower East Siders still long, few people rode the subway and the infrastructure began to crumble, leaving anyone who dared climb below street level faced with dingy stations and trains awash in spray paint.

In the early Eighties Ronay Menschel, a board member of the MTA and a deputy mayor under Ed Koch, founded a new office within the MTA, Arts for Transit, to commission art under the recently passed Percent for Art legislation. Going forward, one percent of capital funds for each station was allocated for art, and in the beginning, Arts for Transit led efforts to save the existing historic terra cotta and mosaics designed by Heins & LaFarge and Squire Vickers. But since the New York City subway falls under the state’s remit, station restoration falls under the jurisdiction of Capital Program and the State Historic Preservation Office. “The NYC Transit cleaning department is responsible during the operational life of a station,” says Sandra Bloodworth. “If it cannot do it, the restoration goes to a capital program — Percent for Art is the only time we can touch it.”

At first, says Bloodworth, who joined the program in 1988 from a background in arts education and became director in 1996, no New Yorker believed that any art could withstand the political, cultural and physical pressure of the millions people who ride the subway every day. But Arts for Transit proved them wrong, starting with Houston Conwill’s “The Open Secret” (1986), a series of bronze reliefs about the sacred spaces of African Americans, mounted on the mezzanine level of the 125th Street Station in Harlem.

Within ten years, the Arts & Design program — a gentle shift in name from Arts for Transit or Percent for Art — had installed forty-eight artworks; by 2013, 250. “Since our last art book, New York’s Underground Art Museum, came out in 2014, the subway has added at least 100 more works,” Bloodworth adds.

But for every 1,000 admirers, there is at least one miscreant. From practically the time she started, Bloodworth says, artists who paint and draw for the project have been given a list of approved materials and fabricators for their work, as well as directions for a set of processes that would ensure their work’s durability, rehabilitation potential and longevity. Sculptors and other creators work in bronze, steel or faceted glass, often where the subway goes above ground. Painters are encouraged to use mosaic.

“Sandra always said ‘as long as the wall is there, your piece is there,’ and that’s true. I had a project manager who was involved in my work every step of the way,” says Lisa Dinhofer, who conceived “Losing My Marbles” for the 42nd Street-Port Authority Station in 2003. “I grew up on the subway; I was born and raised in Brooklyn and was twelve years old when I took the subway to the ‘city’ as we called it, to see the museums. It was my way of giving back.” Following a short blind-jury process, in which Dinhofer submitted a “maquette,” or a mockup of her gold-colored trompe l’oeil frame surrounding a series of marbles which seem to roll across the plane, she vetted two companies, New York-based Miotto Mosaic Studios and Franz Mayer of Munich, and within a few months saw her vision realized in the tunnels.

When she was considering submitting, Dinhofer says, her partner told her that with 500,000 people traveling through the Port Authority every day, “more people are going to see your piece on New Year’s Eve than all of your shows put together, even after twenty years.” Because of that visibility, Dinhofer willingly takes the risk. “It’s the subway — anything can happen. I am just really happy it’s there, and I’m more inclined to think like Milton Glaser” — that changes to the subway art are not necessarily problematic, but emblematic of the relationship between art and the city.

However, if she had the floor at an Arts & Design meeting, Dinhofer would suggest a conservation department. “Every major museum has a department of conservation, and right now, the MTA has essentially created a contemporary art museum underground. There is that Lichtenstein, which is an enamel piece, at 42nd Street and the Ralph Fasanella [oil] at 53rd Street, which I am not sure they ever got around to lighting again.”

Dinhofer and many other artists may get their wish.

On March 20, the MTA announced its Re-NEW-vation Program with the goal of renovating the older, historic stations, from undertaking concrete repairs and water mitigation efforts to replacing tiles along the station walls, and deep cleaning everything. So far this year, the MTA has completed eleven of twelve scheduled facelifts and is on track to complete fifty by the end of the year, including Morgan Avenue, whose Squire Vickers’ tiles are obscured by graffiti, and Delancey/Essex, which needs scouring. But so far, the Arts & Design program has not mentioned replacing faceted glass panels missing from “Jammin’ Under the El” by Verna Hart (1999) at Myrtle Avenue or “Looking Up” by Michael Krondl (2004) at Neptune Avenue, scrubbing the paint and marker off “Migration” by Robin Holder (2006) at Flushing Avenue or retouching the water-damaged “Coney Island Reliefs” by sculptor Deborah Masters (2010) at Stillwell Avenue.

To be fair, the MTA suffered considerably during Covid. The New York transit system will be running on a projected deficit of $1.6 billion in 2024. Its proposal to reduce budg- et gaps through 2028 by an average of $915 million annually leaves many wondering how the subway and commuter trains will keep running when federal aid runs out, let alone how the MTA can showcase new art.

Still, Bloodworth promises that “we will continue to provide durable works of art that are beloved by New Yorkers.” Some extra revenue could come from sales of another book to be released in 2024. Other artists would love to see the Subway Museum mount an exhibition featuring the maquettes, the clay studies called bozzetti and the other influences that go into each work of art.

In the end, however, the pioneering creators of the MTA Museum have accepted a bit of “Zen detachment,” according to Bates, when it comes to the pieces installed — possibly the most racially, ethnically, intellectually and gender-diverse collection of art among any of the institutions of New York. “I would never want the conservation to supersede the new work, because the new work keeps the subway exciting,” Dinhofer says. “New York is constantly reinventing itself for better or worse and people are experiencing it in different ways. Some people are going to come out of the Port Authority every day and forget about it, while others are going to think they saw something very special, whether mine is there in 1,000 years or something else.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2023 World edition.