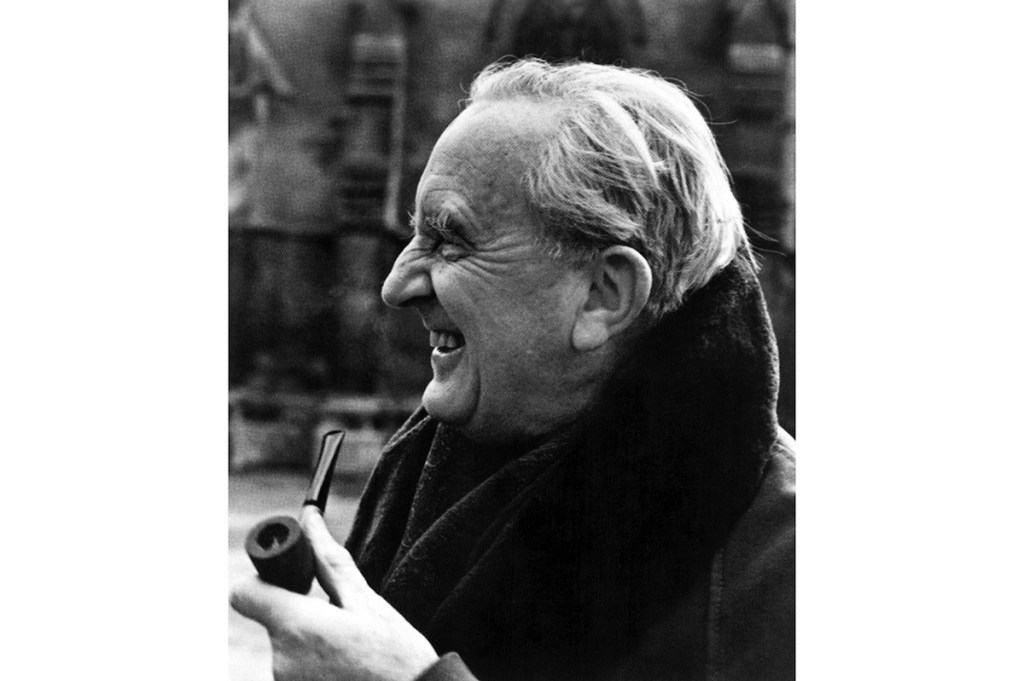

Last year’s big-budget, much talked-about television series, Amazon’s The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power, had a somewhat unlikely figure as its presiding genius. For one thing, he has been dead half a century this year, and for another, he was a mild-mannered Oxford don with a particular scholarly interest in Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse literature. His reputation rests on four novels published during his lifetime, which have not only been bestsellers since their publications in 1937, 1954 and 1955, but continue to attract millions of readers, who are unusually ardent in their appreciation. A sextet of big-budget film adaptations — three good, three bad — has only helped maintain the reputation of a man who, legend has it, created the world of Middle-earth when he idly scribbled the words “in a hole in a ground there lived a hobbit” on a student’s test paper.

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien — better known by his initials — is one of the most beloved writers of the twentieth century. The books he remains best known for, The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings trilogy, may be high fantasy, but the skill of their creation and the painstaking detail of both character and setting have meant that they have long since transcended any generic limitations. While, of course, they are pored over by men with long hair, straggly beards and a tendency to argue over the most minor of plot points (mention the words “Tom Bombadil” in their presence and be prepared for physical violence), their global readership is both vast and continually appreciative. It is estimated that The Lord of the Rings has sold around half a billion copies worldwide since its publication, which puts Professor Tolkien comfortably in the league of all-time bestselling authors, behind only the far more prolific likes of Agatha Christie, Georges Simenon and — alas — Barbara Cartland.

Yet for someone whose books have given such pleasure to so many, and have continued to appear in further installments drawing on his unpublished papers (the most recent, The Fall of Númenor, was published only last year), remarkably little is known about the private life of Tolkien, other than the well-documented basic facts. He was born in South Africa in 1892, grew up in rural England, studied at Oxford, fought at the Somme, returned to Oxford to pursue an academic career, began writing novels in his mid-forties and, by the end of his life, was all but exhausted by the crushing weight of the fame that had settled upon him. He married relatively young, at twenty-four, and had four children. Dying at the age of eighty-one in the seaside resort of Bournemouth, on the south coast of England, he could take pleasure in the knowledge that he had lived a life without scandal or incident.

At least, that is how the sanctioned version of the Tolkien story goes. Yet there are numerous peculiarities which have never satisfactorily been explored or explained. His eldest son John, a priest, has been the object of increasingly concrete allegations of sexual assault both before and after his death in 2003, and a tape recording surfaced in 2019 that suggested that he himself had been molested as a child by friends of his father.

In the recording, John said, “When I was a boy I was constantly surrounded by my father and colleagues of my father. Almost without exception, his colleagues were academics and, you know, some of them were pretty strange fellows… Often, people would stay the night at our house… I often awoke in the morning to find someone sharing my bed… [one] particular person who I loved dearly, not in a sexual way, this person would be fast asleep, huddled up next to me when I woke in the morning. Well, let’s say things had gone on in the night. I knew this. If you wake up with your pajamas off and they were on when you went to sleep, you would wonder, wouldn’t you?”

It remains impossible to know whether any of this took place with his father’s knowledge, or what his reaction would have been if he had discovered it later in life. However, Tolkien has also faced accusations of antisemitism; he did not help his case by saying, in a 1964 BBC radio interview, of the dwarves in his books, “Wouldn’t you say that in many ways they remind you of the Jews? Their words are Semitic obviously, constructed to be Semitic… this is a tremendous love of the artifact, and of course the immense warlike capacity of the Jews, which we tend to forget nowadays.” These remarks may have been the offhand comments of an elderly, unworldly academic, ambiguous in their implications and even intended as praise, or could have suggested something more sinister and decidedly unhelpful to his reputation.

Tolkien’s defenders are quick to point to a letter he wrote to his German publisher in 1938, in which, asked for proof of his “Aryan descent,” he replied scornfully that “if I am to understand that you are enquiring whether I am of Jewish origin, I can only reply that I regret that I appear to have no ancestors of that gifted people.” He also denounced the deterministic Nazi race-doctrine as “wholly pernicious and unscientific.” Yet despite this sort of abundant information about his opinions, there remains a question mark as to what, exactly, Tolkien’s personal views were.

Under normal circumstances, we would have several biographies, full of anecdote and color and revelation, as we do about virtually every major twentieth century author. Tolkien’s papers are kept at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, and would undoubtedly be of use to any authorized biographer. Yet since the publication of Humphrey Carpenter’s J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography in 1977, there has been no officially sanctioned account of his life, nor is one planned.

The reasons for this are complex. As the Tolkien scholar Mark Atherton, whose There and Back Again: J.R.R. Tolkien and the Origins of the Hobbit was published in 2012, told me, “The Tolkien estate and the publishers have been at pains to protect the privacy of Tolkien’s life. There are problems gaining the requisite permission to quote from the unpublished writings of JRRT, or large sums of money have had to be paid to quote at great length from Tolkien’s writings, and some documents are said to be inaccessible.”

The biographer D.J. Taylor concurs, saying, “It’s all down to the constraining hand of the estate, I fear, for whom only a sanitized version of his life and opinions will do. Humphrey Carpenter told me that when he wrote the only proper biography in the mid-1970s, it originally contained two chapters entitled ‘Tolkien the Man.’ These were immediately binned by Tolkien’s second son Christopher, to whom Carpenter, as an apprentice biographer in his twenties, naturally deferred.”

Since then, nobody has been allowed untrammeled access to the papers, let alone the chance to write a full biography; Atherton suggests that one reason for this was the infamous episode when the American company Ace Books released a “pirated” paperback edition of The Lord of the Rings in 1965. Whatever its origins, this caution has meant that, although a reverential (and financially unsuccessful) biopic of Tolkien’s early life, starring Nicholas Hoult, was released in 2019, biographers are kept at arms’ length. (The Tolkien estate was contacted for comment for this piece, but did not respond.)

Both Atherton and Taylor agree that this is a pity. Atherton suggests that matters might be easier now that Christopher, the notably zealous defender of the family brand, has died: “With a new generation now taking over the Tolkien estate, perhaps we can look forward in the future to new biographical studies in which the authors have access and permission to see all the documents and to quote much more fully from them.” And as Taylor says, there is no time to waste. “You would hope that now Christopher is dead, the estate would take a more emollient line. But something needs to be done fast to catch all those elderly dons who remember him from the 1960s, such as Professor John Carey who recalls playing bowls with him on the Merton lawn.”

A definitive, painstakingly researched Tolkien biography would surely be one of the publishing world’s most anticipated and necessary studies. Although the author himself was dismissive of such exploration — Carpenter wrote that Tolkien “disapproved of biography as an aid to literary appreciation” and suggested that what needed to be known of his life could be found in his books — the continued interest in his work, in addition to the inevitable interest in previously unreported details of his private life, surely mean that the time has come for the Tolkien estate to take a more liberal line, open up the archives to reputable biographers and see what happens. I suspect a major biography would vindicate and exculpate the writer, rather than damn him, but without its sanctioned existence, all must remain frustratingly speculative.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2023 World edition.