One of the lesser-known schools of modern philosophy is the Philosophy of Moomin. Like Cynicism or Epicureanism, it is difficult to pin down precisely, but subscribers speak of the importance of the individual, of liberalism and acceptance, and of the life-affirming joy of feeling. In the words of Moominpappa:

Just think, never to be glad or disappointed. Never to like anyone and get cross at him and forgive him. Never to sleep or feel cold, never to make a mistake and have a stomach-ache and be cured from it, never to have a birthday party, drink beer, and have a bad conscience… How terrible.

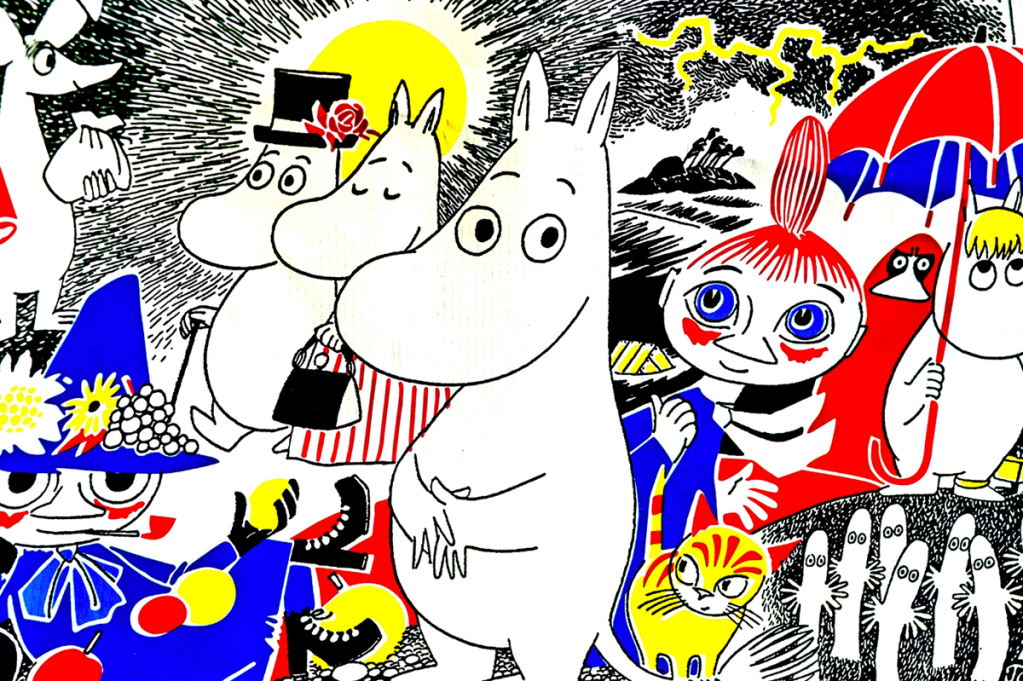

Within this philosophical school, Moominpappa’s wife, Moominmamma, may be likened to Socrates; their son, Moomintroll, to Plato; while Fillyjonk, the solitary control freak, is Kierkegaard, only thinner and better dressed. The philosophy — not wholly tongue-in-cheek — falls under a broader “Moomin Phenomenon,” which might be translated as “Moomin Obsession,” and is global in its reach.

Jennifer Saunders, who presents a new five-part series on the phenomenon (actress Lily Collins provides an accompanying audio guide), does not take it too seriously, which is a relief, given that most of the people she interviews are superfans. We begin in a tattoo parlor in Sweden, where a young woman is having her nth Moomin inking. Later on, we find ourselves in the shop of Moominvalley Park outside Tokyo, where there is much enthusiasm for the “cute” creatures, but little way of conveying this down the airwaves. You’d have thought that a budget big enough to cover trips to Sweden, Finland and Japan would also have stretched to a Japanese translator.

Saunders, who voiced Mymble in the recent Moominvalley TV series, rather pointedly defines herself as “a wholehearted admirer” of the franchise as opposed to a “fan.” Actor Samuel West, meanwhile, outs himself as a Moomin obsessive who named one of his daughters after Little My: “We wanted her to be that person and she is that person.”

The episodes on Moomin fans and Moomin branding are okay. The episodes on Moomin philosophy and Moomin creator Tove Jansson are tremendous fun. Although we never get to the bottom of whether Nietzsche would have found Snufkin delusional, or whether Mary Wollstonecraft would have championed Little My’s “righteous anger” — two of the hypotheses offered by the ever-entertaining Saunders — we are treated to some mind-broadening tutorials with cheery, Moomin-inclined academics.

It is interesting to hear Jansson’s biography set out against the social history of Finland and the opportunities available to female artists. I had no idea, for example, that women in Finland were given the vote as early as 1906. I also enjoyed the visit to the (restored) outdoor loos used by Jansson and her brothers when they were growing up. The toilets faced each other, and an animal-shaped doodle on one of the walls, believed to be an attempt by Jansson to scare one brother, has been described, perhaps optimistically, as the beginnings of Moomin.

If there is one piece of Moomin philosophy I shall take away from this quirky, uplifting tour, it is that every dull job can become an adventure, if you only combine it with something different.

Applying this philosophy to cooking, I put on Why Women Grow, a new gardening podcast from the journalist and author Alice Vincent, while I chop turnips and bemoan the shortage of fresh veg. Some of Vincent’s guests certainly make grow-your-own sound very appealing. Cookbook author Rukmini Iyer had me practically salivating over her Galina tomatoes and baby eggplants.

Sarah Raven was similarly inspiring as she described her method of flower-arranging by selecting “a bride” as a main flower, then bridesmaids, and finally a contrasting “gatecrasher” to cut through the other flowers “like lemon over smoked salmon.” All the guests, in fact, provide some interesting insights into their gardening habits. As a whole, however, I found the podcast rather lackluster. “Gosh, it’s so dry,” as one of the contributors says of her soil. As lovely as it is to be walked around a stranger’s garden and hear the occasional buzz of a bee or slice of the secateurs, it is no replacement for actually being there.

When a stylist and “purveyor of joy” spoke of her preference for retaining rather than clearing her rotten cabbages and surplus beetroot leaves because they look pretty, I wanted to know what the implications of this approach could be for the soil and surrounding plants. It would have been nice to hear some deeper commentary on the tension between aesthetics and nature, and on the philosophy of planting as a woman, given the title of the podcast, which is based upon Vincent’s book.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.