I visited Sicily in May 2005, when the airlines were still requiring all checked luggage to be left unlocked. After the flight from Paris touched down at Palermo, my wife and I went to collect our luggage at an apparently quiet and unrushed airport to discover my suitcase opened partway and an expensive dressing gown missing. Eighteen years ago, il Commissario Salvatore Montalbano was quite unknown to me. Otherwise, I should have immediately thought of the Sinagra family at the eastern end of the island, though the word “mafia” did come to mind as I rezipped the bag.

I was not to discover until a decade later that a brilliant author named Andrea Camilleri had written twenty-seven crime novels centered on the police commissariat in the fictitious Sicilian town of Vigàta, including, beyond Montalbano himself, his lieutenants Giuseppe Fazio, Mimì Augello, Galluzzo and Catarella; that the first volume in the series, La forma dell’acqua (The Shape of Water) had been published in 1994; and that the first of the hugely popular RAI TV series had aired in 1999.

It was through these films that I came at last to the novels, a fair number of which I read in Italian before the Sicilian dialect crowded out peninsular Italian to the degree that I could no longer comprehend the text. (If a Sicilian-Italian dictionary beyond a tourists’ phrase book exists, I have yet to discover it.) The Montalbano novels are exquisite literary works on the order of Simenon’s Maigrets or Chandler’s Marlowe books rather than of Agatha Christie’s overly contrived “mysteries”: spare, taut, concise, realistic and plausible, concerned chiefly with character, mood and setting — always setting.

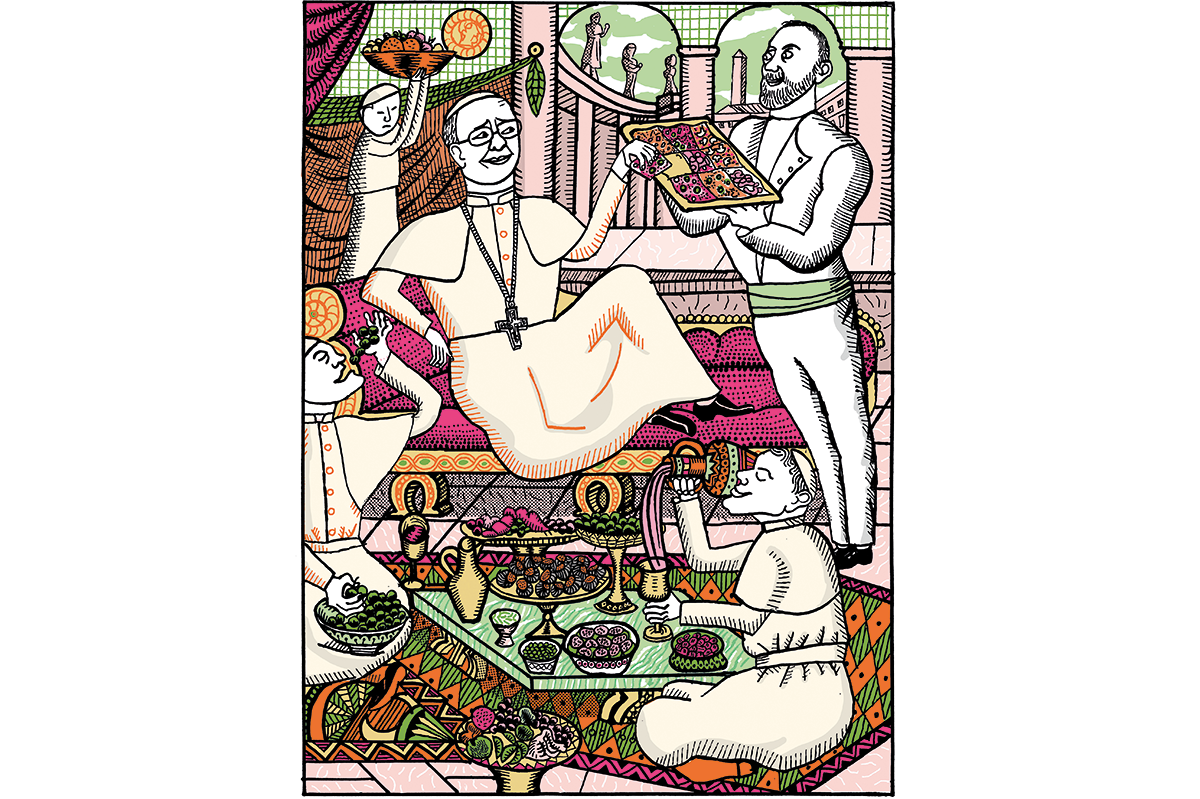

Italy is a civilization that was made through, by and indeed for art, in a geographical location that is one of God’s most supreme natural creations and for which Italians have never shown themselves ungrateful. I mean the Italians as a people, not Italian artists alone. The Schoolmen, as Jacques Maritain explained in Art and Scholasticism, had a broad understanding of “art” that went beyond the fine arts to include anything made by the human mind and hand: a ship, a piece of crockery, a fine wine, a good meal. (St. Thomas Aquinas held that art is reason in making a virtue of the practical intellect.)

Italy, more than most countries, has a culture that learned many centuries ago to graft reason to sensibility, intellectuality to sensuality: a fact that Camilleri and the original director of the series, Alberto Sironi, never forgot or neglected to exploit. Given Camilleri’s brilliant texts to work from; the superb soundtrack by Franco Piersanti that combines pleasing melody with striking and effective dissonance; the inspired acting; the masterful cinematography that makes the absolute most of the intricate architectural baroque splendor of “Vigàta” (in reality, the filming was done in a number of towns in southeastern Sicily) and the tortuous hill country in which the small city is built, to say nothing of the lapping Mediterranean, as changeable as the female characters whose lush physical beauty is beyond anything the Hollywood moguls ever dreamt of; and the dishes casually served up to Montalbano at his local restaurant that make cookbook photos look like papier-mâché — the resulting masterpiece was virtually inevitable.

Erle Stanley Gardner took one look at Raymond Burr and said, “He is Perry Mason.” If Andrea Camilleri didn’t say the same of Luca Zingaretti, he should have done. It is easy of course, alternately reading the novels and watching the films, to allow one’s visual impressions to influence the literary ones. Still, it is difficult not to feel that Zingaretti perfectly captures the brusque, authoritative, commanding, frequently impatient but nearly always good-natured, thoroughly masculine character of the Sicilian police detective Camilleri created on paper. In the novels, Salvo is popular with his men — as well as with every woman he encounters — and Zingaretti makes it is easy to see why. His subordinates Fazio, Augello and Galluzzo maintain an appropriately respectful, almost filial, manner toward their capo while retaining their distinctive personalities in their capable pursuit of their assignments.

One of the series’ most popular characters is Agatino Catarella (Angelo Russo), the police officer who is confined largely to headquarters where he is entrusted with maintaining the computer system and announcing visitors to the station. He adds a comedic element through his linguistic oddities, malapropisms and mispronunciations (“in pirsona pirsonalmente, Commissario!”) and his habitual loss of motor control in flinging wide the double doors to Montalbano’s office.

However repetitive the assigned foibles of his role, Russo is always amusing. Yet — in one of the series’ most memorable scenes — he demonstrates himself to be a tragic actor of considerable depth when Catarella undertakes a role in a local passion play. Katharina Böhm as Livia, Montalbano’s mistress of convenience who visits him sporadically from her home in Genoa (regularly importuning him to marry her) handles a difficult part superbly. As with every television show endowed with notable longevity, Il Commissario Montalbano suffered attrition due to age; in addition to Sironi’s death in 2019, the series suffered the loss of the incomparable Marcello Perracchio, who played the forensic coroner, in 2017.

Camilleri himself went to his grave in 2019 aged ninety-three, leaving the final Montalbano novel, Riccardino, written between July 2004 and July 2005, for publication the following year. It appeared in Italy in July 2020 and was released two months later in the United States.

The novel is a puzzle, starting with the matter of the decade and a half between its completion and publication. Camilleri, it seems, was bored with the series and the final volume itself, on which he worked with waning enthusiasm. The story, which concerns four cement-plant colleagues who conspire to operate a drug smuggling business, is typical enough, but beyond that a great deal has changed.

Montalbano, feeling his age, no longer approaches his cases with gusto, as his colleagues observe. Indeed, he is now scarcely recognizable — passive, flaccid and unexpressive — whether by authorial intention or not. Aware perhaps of his own lack of interest, Camilleri has invented a new character, The Author, who acts as Montalbano’s alter ego, faxing and phoning him to complain of the way in which he is conducting the investigation and suggesting scenarios of his own, all of which Salvo naturally resents. The literary device is one Camilleri borrowed from Luigi Pirandello (1867-1936), the Sicilian playwright and novelist on whose work he was something of an expert. It is not wholly successful, however, although the ending — in which Montalbano, having decided that la commedia è finita, literally erases himself from the story and from existence itself — has genuine effect and pathos.

The chief problem with the book appears to be the translator, Stephen Sartarelli, a native of Youngstown, Ohio, now resident in France; a poet and the translator of several books, including two of the Montalbano novels, including the first of them, La forma dell’aqua. As I did not read Riccardino in the original, I cannot say authoritatively whether the flatness of the English translation reflects Camilleri’s fading powers as a writer and stylist or was imposed upon the book by Sarterelli. I can state that, having compared passages from La voce del violino, La gita a Tindari and a couple of other titles with ones taken from Riccardino, I find the difference startling: it is the one between the work of a master and that of an amateur — or worse, a creative writing student.

One fault at least can be laid squarely at Sartarelli’s feet, and that is his translation of Catarella’s diction which he has put — disastrously — into Brooklynese, so that “in pirsona, pirsonalmente” becomes “in poisson, poissanally.” Regional dialect, of course, is distinct from social differences in pronunciation: Cockney is not British dialect. Having reread Catarella in Italian and re-watched him in a couple of the films, I can say with confidence that his accent is nowhere near as pronounced as Sartarelli has it, and that he is nearly always as compre- hensible as the other characters in print and on screen. If only from curiosity, I’m tempted to order Riccardino from Sellerio editore, Camilleri’s Italian publisher, and see for myself.

Be that as it may, the translation of the Montalbano novels from page to screen ranks as an artistic triumph as complete as that of Georges Simenon’s Maigret with Bruno Cremer, P.G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster with Stephen Fry and Hugh Laurie and Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited to the eponymous film with Jeremy Irons, Anthony Andrews, Diana Quick, Claire Bloom, Sir Laurence Olivier, et al. In short: il risultato è la perfezione.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply