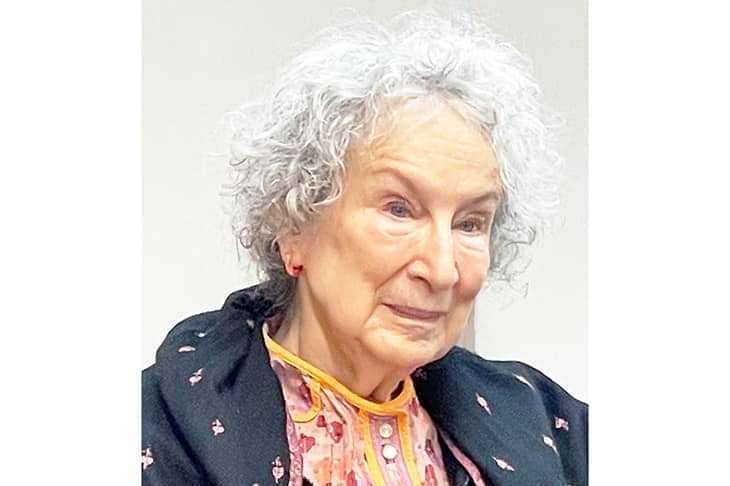

Margaret Atwood is among the major writers of English fiction of our time. This is a very boring way to start a review, but it is true. Atwood, now eighty-two, is prize-winning, popular and prolific. She’s won two Booker Prizes. Several of her books have attained totemic status with readers, most obviously the reproductive dystopia of The Handmaid’s Tale, but also Cat’s Eye, for its steely portrayal of girlhood cruelty, and The Blind Assassin, which combines feminist grit with genre-straddling swagger.

And there are so many books. Seventeen novels, more than a dozen collections of poetry, sundry shorter fictions and children’s stories, and multiple works of non-fiction, of which Burning Questions is the 11th overall and the third compilation of Atwood’s journalism, essays and speeches. It’s an embarrassment of content, and Atwood does sound almost embarrassed about it. In the introduction to Burning Questions she comes close to issuing an apology for the sheer volume of her output:

If you’re asked to write ten occasional essays a year and say no to 90 percent of them, that comes to one essay a year. But if you’re asked to write 400 pieces and you still say no to 90 percent of them — how firm and virtuous you are! — that’s still forty pieces a year. I’ve been averaging forty a year for the last couple of decades. There’s a limit. This has to stop.

There’s an important lesson for writers here: just because someone asks you to do something, you don’t have to say yes. Selectivity is important. Similarly, just because you’ve written something, you don’t have to put it in your collected works. This is something Atwood could do with working on; Burning Questions is unrelentingly completist. Here you’ll find book reviews, op-ed pieces, introductions to other books and the texts of speeches to audiences including the Canadian Department of Forestry and PEN International, the free speech group.

Undoubtedly Burning Questions will save literature students a lot of googling: if you want to expand your close reading of Atwood’s Noughties MaddAddam trilogy with reference to her contemporary preoccupations, this book has done the research for you. (Those preoccupations tend to be: the environment and its degradation through human activity, totalitarianism and its consequences for the arts, and, in a low-key way, her own discomfort with being elevated to living legend status.)

Useful, though, is not the same as good. Strip occasional pieces of their occasion — wrest the journalism from its journal, denude the oratory of its audience, sunder the introduction from the text it was intended to introduce — and they are left strangely adrift, unanchored, alienated from their purpose. The perennial danger for any collection like this is that its contents are intended, often, to be of the moment. Outside that moment, they fail.

For example, “Alice Munro: An Appreciation” (the introduction to a 2008 collection of Munro’s stories) begins like this: “Alice Munro is among the major writers of English fiction of our time.” This is true, and perhaps an acceptable way to set out your stall to a reader who has already cracked the spine on their selected Munro, but it is also very boring — more the style of a flailing high-school student’s presentation than a storied author. There are still fine observations in that piece (of Munro’s delicate portrayal of erotic possibility, Atwood writes: “Her characters are as alert as dogs in a perfume store to the sexual chemistry in a gathering”), and elsewhere. The question is whether this is the most engaging form in which to receive them.

It’s also a problem that when a writer’s work is all bunched up like this, their shortcuts become apparent. Atwood sometimes pretends to a kind of strategic naivety (for example, claiming a childlike incomprehension of the credit system in a essay on debt) that is perfectly serviceable for skipping over the detail in a short word count, but tiresome when you see it repeated several times within the same set of covers.

Burning Questions is best when it shows Atwood either at her most sincere or her most cussed. In “Am I a Bad Feminist?” from 2018, she reflects on the backlash she suffered from the #MeToo movement after she publicly criticized the lack of due process received by an academic accused of sexual misconduct. “Why have accountability and transparency been framed as antithetical to women’s rights?” she demands. It’s a good question, and I would read much more of her on it.

Then there’s her writing on her partner Graeme Gibson, who died in 2019 after several years with dementia. An introduction to a reissue of his novels is simultaneously analytical (she writes of the “Gibsonian style”) and intimate (much of it is about their shared misadventures in smallholding). But what it makes me want more than anything is to read it with Gibson’s novels attached — and not like this, as one resident in an orphanage of writing.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.