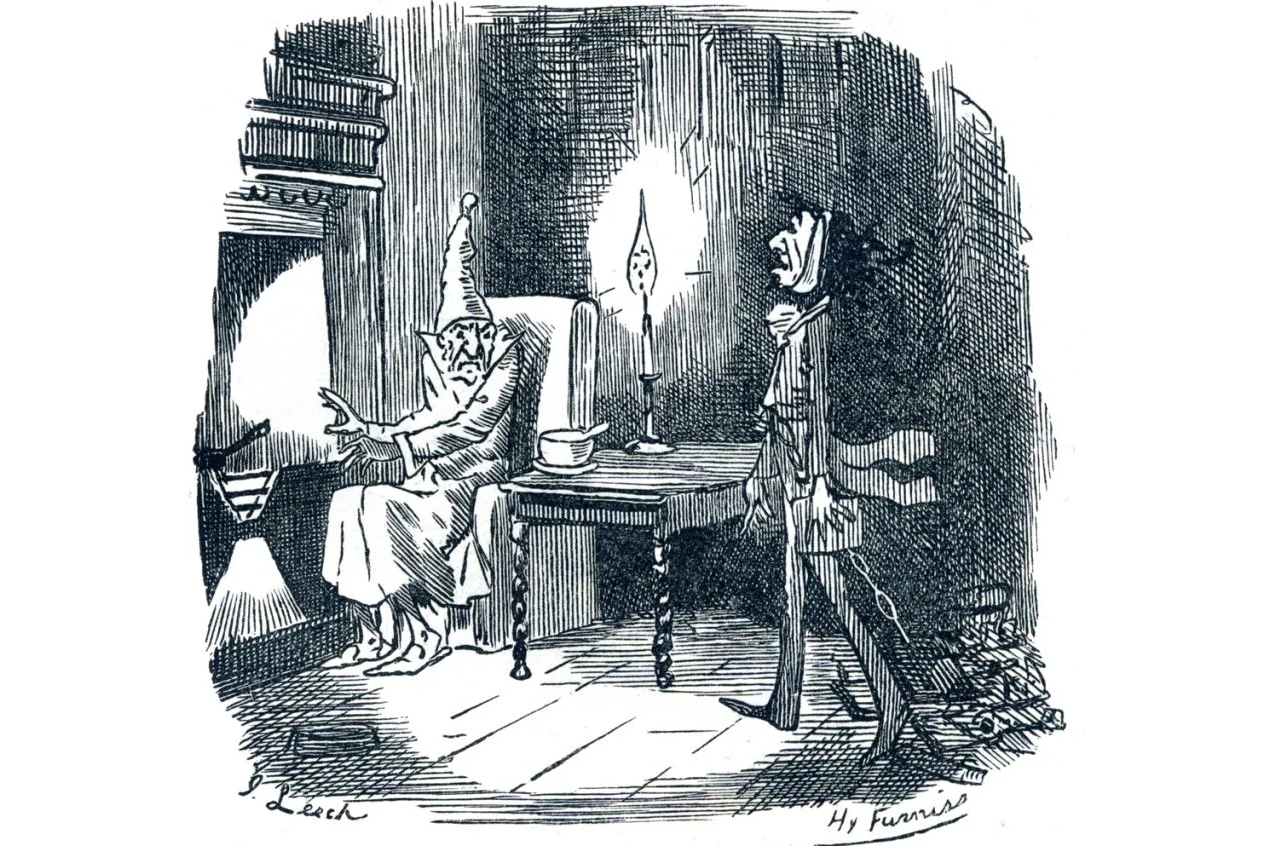

Temperature records for Los Angeles in the summer of 1945 are patchy, but 90 in the shade seems to have been the norm. It was during one such scorcher, presumably, that the songwriters Jule Styne and Sammy Cahn pulled up at a red light on the corner of Hollywood and Vine. Cahn suggested going to the beach. Styne had a better idea: “Let’s go write a winter song.” Driving over to the offices of their publisher Edwin H. Morris, Cahn commandeered a typewriter, glanced out the window and typed the exact opposite of what he saw: “The weather outside is frightful.” The Great American Songbook had acquired another Christmas classic.

And “Let it Snow!” is no less classic — and all the more American — for omitting any mention of Christmas. That wasn’t obligatory (Mel Tormé’s “The Christmas Song” was born in the same Californian heatwave). But in a melting-pot America, it made commercial sense. Many of the seasonal standards created during that glorious mid-century harvest of melody don’t mention Christmas at all — “Winter Wonderland,” “Jingle Bells” — or, if they do, it’s a distinctly secular version: “White Christmas,” “Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer.” Authentically religious Christmas songs have had a checkered history since the baby boom, though rarely as bizarre as the 1976 Johnny Mathis hit “When a Child is Born” — a melody that had previously featured in the Argentinean werewolf movie Nazareno Cruz and the Wolf (“The doves, and the screams!”).

The less specific you can be, the broader the scope for royalties. The question, then, is what — in musical terms — constitutes an irreducible minimum of Christmas-ness? Leroy Anderson cracked it back in 1946. “Sleigh Ride” was conceived (you guessed it) in a heatwave — the catchiest in a long series of impossibly tuneful encores that Anderson composed for the Boston Pops Orchestra. No direct reference to Christmas here (until 1950, “Sleigh Ride” didn’t even have words). Just an infectious tune, Anderson’s Broadway-lite orchestration and (every orchestral brass player’s favorite moment) a swinging jazz-break on the da capo. Oh, and sleigh bells from beginning to end. That’s the secret ingredient: a sonic mulling spice that transforms the most unlikely bottle of classical plonk into a warming festive treat.

Which means, this Christmas, that you might hear your local orchestra playing Mozart’s German Dance K.605 No. 3 — called “Der Schlittenfahrt (Sleigh Ride)” because Mozart (who always had an ear for a hit) added sleigh bells and post-horn. Never mind that he wrote it in February 1791 for the Viennese carnival season. Or there’s “Winter Night,” a snowy little bonbon that Delius actually did write at Christmas 1887 as a gift for his host Edvard Grieg, but which was relaunched as “Sleigh Ride” (probably by Thomas Beecham) a good decade after the composer’s death. It hasn’t looked back.

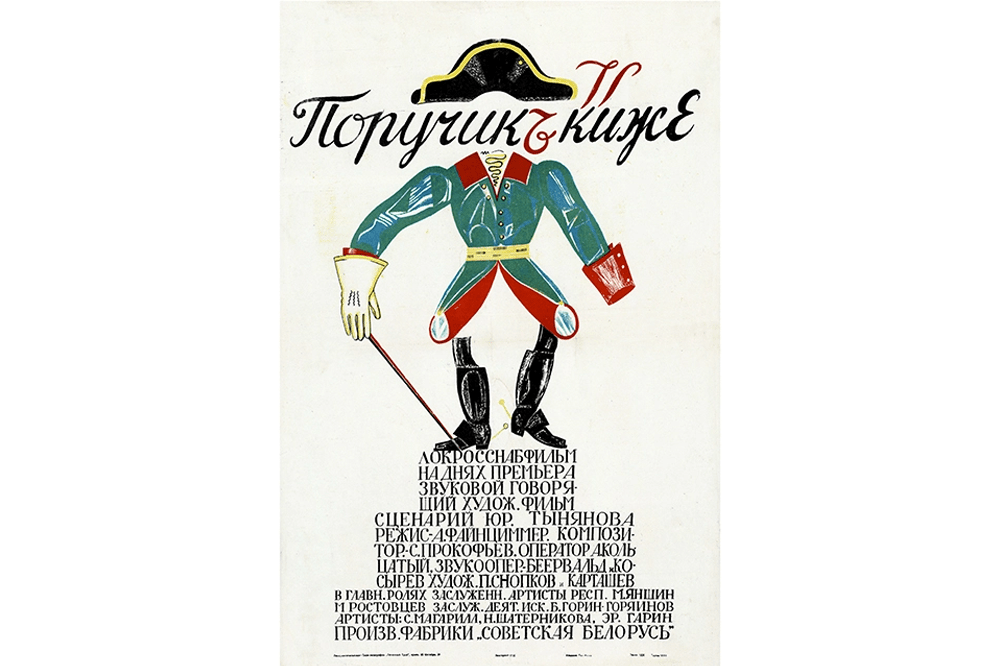

No, once those sleigh bells are jingling, pretty much anything counts as Christmassy. “The entire Cheka must be on the alert to see to it that those who do not show up for work because of Christmas are shot,” announced Lenin, never a man to spoil anyone’s fun. In the 1934 Soviet film Lieutenant Kijé, three steaming drunks fall semi-conscious into a horse-drawn cart. It’s not a sleigh and there’s barely a trace of snow. None of which has prevented western audiences (including prog-rocker Greg Lake, who shoehorned it into his 1975 chart-topper “I Believe in Father Christmas”) from assuming that the Troika from Prokofiev’s film score is a wholesome bit of winter cheer. Sleigh bells, you see. More recently, excerpts from Prokofiev’s 1950 Young Soviet Pioneer commission Winter Bonfire have been popping up in symphonic Christmas concerts. State-enforced atheism has never sounded so festive.

So perhaps there’s still hope for an older, British tradition of co-opted Yuletide classics, and in that spirit here are three sleigh bell-free orchestral stocking-fillers for your seasonal playlist. First, the “Christmas Overture” by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1911); glowing with Edwardian warmth and based on music that he wrote for a play with the enchanting title The Forest of Wild Thyme. Then try “The Merrymakers” by Eric Coates; a jazz-age spritzer of a concert opener from 1923, originally titled “A New Year’s Overture” but renamed when Coates overshot his deadline — and realized that his earnings would be higher if performances weren’t confined to December 31.

Finally, handkerchiefs at the ready for “A Children’s Overture” by Roger Quilter: not a Christmas tune in sight, but the sweetest, most tender medley of nursery rhymes you’ll ever hear. It was composed, heartbreakingly, in 1914, as the overture to the West End Christmas play Where the Rainbow Ends. The characters included Saint George and a lion cub who drinks “Colonial Mixture for British Lions,” so don’t bank on a revival any time soon. Just enjoy Quilter’s fireside colors and scented late-Romantic harmonies. The nice thing about secular Christmas music is that no one expects you to overthink it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.