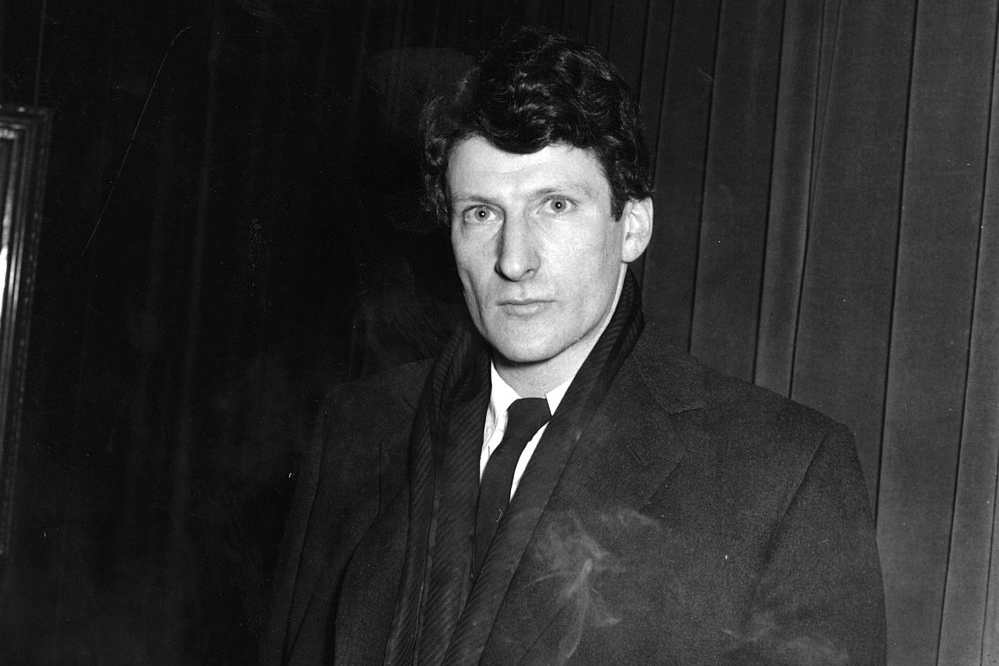

One of Lucian Freud’s firmly fixed views about himself was ‘I’m not at all introspective’. This was, like many opinions we hold about ourselves, both true and not true. Perhaps it was more that he did not want to look within: his gaze was directed outwards. Lucian had trained himself to see everything — animate and inanimate — without preconceptions (one of his anxieties was that his own feelings would leak into a picture and spoil it). But looking at oneself and at another person are processes that are fundamentally dissimilar, both practically and psychologically. This puts his self-portraits, which are on show in an exhibition at the Royal Academy in London next week, in a separate category to the rest of his work.

Lucian disliked being the focus of attention — even refusing to turn up to his own private views — and hated having his picture snapped by strangers. One day in the mid-1990s I was having lunch with him at St John restaurant, when he suddenly stood up and started hurling bread rolls at another customer. It turned out he suspected this person — wrongly, as it happened — of taking his photograph.

This was paradoxical because, of course, he spent much of his time observing other people, in his studio and elsewhere. In restaurants he would quite frequently stare hard at a fellow diner. The recipient of this attention sometimes found it unnerving, especially as Lucian had a habit of raising his upper eyelid to see more clearly, which gave him the look of a bird of prey. A well-known chat-show host once told me that he found the Freudian scrutiny he had been subjected to in the Wolseley ‘terrifying’. But actually, Lucian was just sizing him up as a potential subject for a picture.

He thought of himself, sometimes, as a latter-day version of the Caliph Harun al-Rashid, who slipped out of his palace in disguise by night to mingle with the citizens of Baghdad. In the same way, Lucian thought of London as his city, and all the people in it as potential pictures if they were interesting enough. The one person he could not scrutinize in this way, of course, was himself.

In ‘To a Louse’, the Scottish poet Robert Burns famously wished some higher power would give us the ability ‘to see oursels as ithers see us’. But, as Burns seemed to acknowledge, that’s impossible, strictly speaking. All we can ever see is a reflection in a mirror or a secondary image, such as a photograph. And that’s not the same at all.

We arrange our features for the camera or the looking-glass. We pose and produce an unnatural grin, even — or especially —for selfies. If a likeness doesn’t please us, we delete it. That’s why Lucian often added the word ‘reflection’ to the title of his self–portraits. He wanted to stress that this is a painting of light bouncing off glass.

A little painting from 1967, ‘Interior with Hand Mirror (Self-portrait)’, makes the point poetically. The small looking-glass is propped in the sash window of Lucian’s studio — then a condemned 19th-century terraced house in Paddington. The painter’s face is hazy in comparison with the wood-work of the window frame (of which he painted a careful portrait). This is, as much as anything, a depiction of two kinds of light: the London day outside, and the sort in the mirror image — dimmer and less distinct.

Lucian was a connoisseur of differing qualities of light, his favorite being the kind he encountered in Dublin, filtered through high, thin cloud. He disliked strong sunlight because it produced too much glare, complaining that it prevented him ‘seeing the forms properly’. Once when I was talking to him in his studio, he noted that light was better than it had been a few minutes before. ‘Brighter?’ I asked. ‘Clearer,’ he replied.

Part of his life’s effort was to see things really, really clearly. Consequently, from quite early on Lucian preferred not to work outdoors. All his mature landscapes were done from inside a room, looking through the window. He also disliked painting en plein air because, away from the studio, there was a danger that strangers would stop and watch him.

When contemplating another person Lucian could be alarmingly intuitive. He was able to guess what was going on inside your head just by looking at you. With the pictures of himself, however, it was naturally different.

He noted with interest the physical changes brought by age — or, in the case of ‘Self Portrait with Black Eye’, an altercation with a taxi driver. For ‘Painter Working, Reflection’, 1993, he scrutinized himself stark naked, at the age of 70, brush flourished in one hand, palette in the other. The fundamental subject, though, was always Lucian watching himself observing his own features — not directly but, as St Paul put it, in ‘a glass, darkly’.