You’re sick of cancel culture, and you’re not alone. Just last week, the fashion designer Tom Ford complained that cancel culture “‘inhibits design’ because ‘everything is now considered appropriation’ and designers can no longer ‘celebrate other cultures’.” The actress Dakota Johnson, famous until recently for being the daughter of Don Johnson and Melanie Griffith, told The Hollywood Reporter she finds the whole thing — and I do mean the whole thing — sad. “I feel sad for the loss of great artists. I feel sad for people needing help and perhaps not getting it in time. I feel sad for anyone who was harmed or hurt. It’s just really sad.”

Even The New York Times got in on the regret, with Jennifer Finney Boylan wondering whether we should cancel a supposedly good song by a bad man named Don McLean. She goes with canceling: “For a lot of baby boomers, it’s painful to realize that some of the songs first lodged in our memories in adolescence really need a second look,” and if you’re a Boomer, you know there’s nothing more painful than questioning your adolescence.

Most Americans agree with Tom Ford that there’s something wrong with cancel culture. In a recent poll conducted by The Hill, 71 percent of respondents said cancel culture had “gone too far,” and 69 percent said it “unfairly punishes people for their past actions or statements.” The question for most people, including Finney Boylan in the Times, is precisely this: is it fair to erase certain works from history because of the bad things people have done?

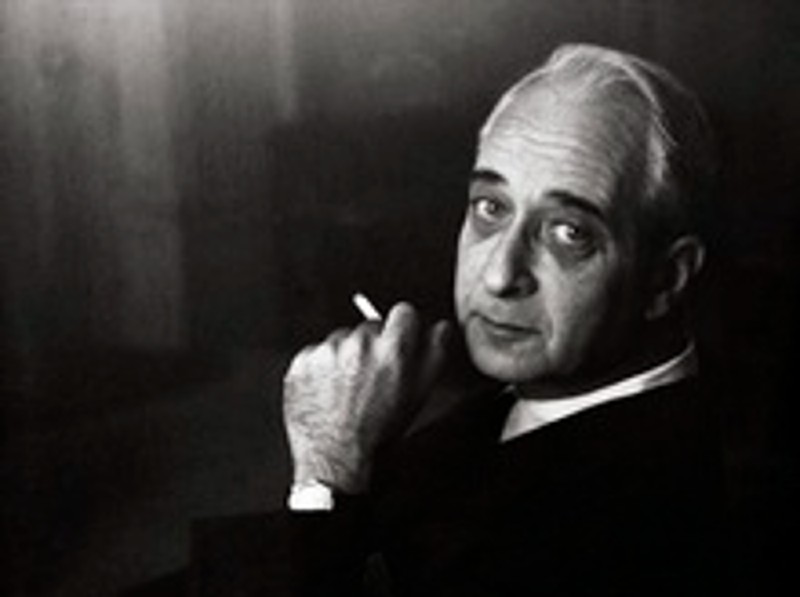

This question would have been absurd to Lionel Trilling, the great liberal cultural critic. In his essay “The Sense of the Past,” he argues that we cannot understand ourselves, much less the world, without understanding the past, however unseemly it might be. The essay is a response to the New Critics, whom Trilling characterizes, fairly or not, as barring any consideration of history from evaluating a work’s literary merit. But it also provides a broader defense of history that is worth revisiting today, even if you are, like me, almost as tired of responses to cancel culture as cancel culture itself.

Trilling writes that forgetting the past — or remembering only a simplified version of it — is a kind of escapism: “Without the sense of the past we might be more certain, less weighted down and apprehensive.” It is much easier to believe in progress if one gets rid of history completely and lives as if the present way of life “shall be satisfactory once and for all, time without end.” We don’t want to be reminded, Trilling continues, “that our present is but perpetuating mistakes and failures and instituting new troubles.”

That is a simple but revelatory point. It means that to cancel the past is not an act of justice, though it is often presented as such, but an act of injustice, not so much towards the people of the past, but towards ourselves. It allows us to be “less aware” of our own failings and, therefore, “less generous.” It shows us that cancel culture couches a fear of facing reality in the language of courage. It makes clear that attacks on the past celebrate ignorance as a kind of knowledge.

Trilling writes that anti-historicism is the result of thinking that “bad ideas” are to be blamed for our problems rather than “bad thinking”: “We have come to believe that some ideas can betray us, others save us. The educated classes are learning to blame ideas for our troubles, rather than blaming what is a very different thing—our own bad thinking.”

This temptation to focus on bad ideas rather than bad thinking is particularly common in “a time of war” — real or cultural — because it creates a very clearly defined enemy (however illusory) that can then be attacked. Both sides in a war need to believe in “the fixed, immutable nature of the ideas to which each side owes allegiance. What gods were to the ancients at war, ideas are to us.” The concept of antiracism, for example, may be the result of poor thinking, but it’s a great idea in Trilling’s sense of the term. Its simplicity is the source of its effectiveness as a weapon.

Unsurprisingly for Trilling “our growing estrangement from history” is not a sign of a culture’s progress but its decline. “The historical sense…is to be understood as the critical sense, as the sense which life uses to test itself. And since there never was a time when the instinct for divining—and ‘quickly’!—the order of rank of cultural expressions was so much needed, our growing estrangement from history must be understood as the sign of our desperation.”

Trilling is referring to the right here — the conservative New Critics — and deploring their need to “rank” works of art according to aesthetic criteria alone. Had he lived to see it, he would have been equally disgusted at the left’s need to cleanse art and history without any consideration of merit at all.