Without a space or a location, ‘the movies’ cease to exist. They become another niche interest with little to no cultural penetration. Awards-season movies, summer blockbusters, sleeper hits and all kinds of popular film phenomena cease to exist without theaters themselves. The last year has shown how much movie culture relies on the activity of going to the movies and the physical space itself.

The Last Blockbuster is a documentary about the death of another space: video stores, albeit through the eyes of the last representatives of a corporation that destroyed vast swaths of mom & pop stores across America. Lloyd Kaufman, the co-founder of Troma Entertainment, an independent film distribution company, is an understandably hostile subject. After questioning the credibility of the filmmakers, he ends his brief appearance thus: ‘I have nothing good to say about Blockbuster.’

The director, Taylor Morden, and many of his subjects are clearly nostalgic for Blockbuster, and spend as much time on the universal experience of going to a video store, with its variety of sensations and rituals, as on the memories of employees who writhe in nostalgia for blue carpets and yellow plastic. But The Last Blockbuster is not about Blockbuster or its history, or even its notorious internal censorship policy which created mangled cuts of films like Bad Lieutenant and David Cronenberg’s Crash. Morden’s film follows a family in Bend, Oregon as they cling to the flotsam of corporate collapse and divestment.

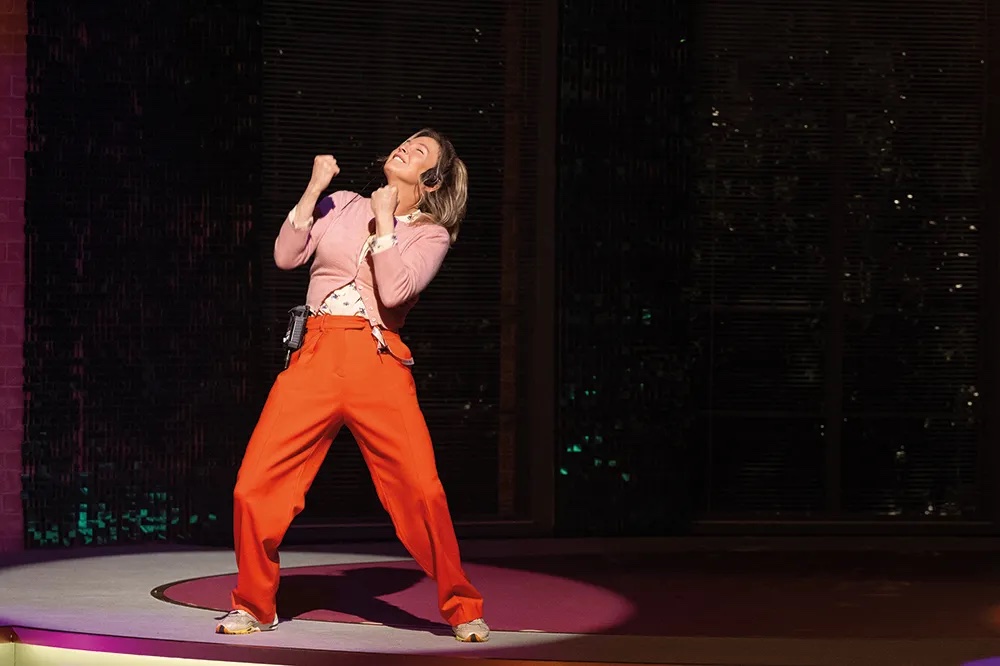

Sandi Harding is the star of The Last Blockbuster. Along with her family of seven, she holds the line on one of the last remaining operating video-rental stores in the United States. When video stores were thriving, Harding and her husband started Pacific Video, which people assumed was a chain. Business boomed, and in the early 1990s Blockbuster gave them an ultimatum: franchise with us or we’re opening a store in your neighborhood. They decided to survive, and rebranded as a Blockbuster. It operated as a proper franchise unit until 2014. Since then, Harding has shouldered most of the work, stocking her store using her own money to buy new movies and snacks on trips to Target, Walmart and Costco. No more shipments from headquarters.

We watch Harding as she dusts off old computer parts to keep her store’s inventory operating, and holds off any suggestions to retire or become ‘snowbirds’ until Blockbuster finally pulls the plug and refuses to renew their license. Up to then, there is no retirement. This semi-religious attitude towards movie culture is not uncommon or unique to Bend. In a postscript in the credits, we learn that the shop has even weathered the coronavirus pandemic. This is the diehard’s dilemma. Can you live on a sinking ship? What can we give back on the way down?

The specter of a lease renewal with Dish Services looms throughout the film, but otherwise, people in Bend still like going to the video store. There are holdouts in major cities and new projects that have shown promise (like Beyond Video in Baltimore, and Vidiots and Videotheque in Los Angeles), but for most people in this country the experience of ‘going to the video store’ is no longer possible. ‘Awards season loses its shine when no one can go to the cinema,’ Fiona Mountford wrote in The Spectator in March. ‘We long for the usual hustle-bustle, the red carpet, the fashion faux pas, and the rictus grins of the losers.’ As many of those interviewed say, going to a video store with someone — or alone — was an experience in itself, and not to be dismissed as an inconvenience that has been fixed by the internet. The myth that ‘everything is on streaming’ is, unfortunately, far from true. In terms of movies (not television shows), Netflix has nothing on the 30,000 titles in an average video store.

Adam Brody, Brian Posehn, Kevin Smith, Ione Skye and Jamie Kennedy, among others, go on at length about the pleasures and anxieties and physical sensations associated with video store visits: roaming the aisles, the smell of plastic and popcorn, intimidation by clerk. We are missing out on similar sensations in movie theaters now, which is why we must get back to them as soon as possible. Harding and her family have kept their store open and active, if not thriving, in Bend, though their livelihood is constantly at the mercy of corporate whims. But people keep coming, and in Bend, as in Baltimore and Los Angeles, you can still ‘go to the video store’. How much longer, though, will we ‘go to the movies’?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s June 2021 World edition.