In late July, I had dinner in a London restaurant with Spectator World contributor Fergus Butler-Gallie. Behind us was sitting an American who clearly had a high opinion of himself, judging by the volume with which he spoke, the almost manic fashion he treated his dining guest — the theater director Trevor Nunn — to a series of impersonations and Shakespearean soliloquies, and the way he dominated the dining room. When Nunn left the table, I glanced over and was both amused and vaguely appalled to discover that the diner was none other than Kevin Spacey, fresh from being acquitted of charges of sexual assault, and now, presumably, set on rebuilding his career.

We’d overheard snippets of conversation. Spacey mentioned playing the lead in Timon of Athens — it might be appealing to play a misanthrope who seeks revenge on those who took his hospitality and then rejected him when his money is extinguished — and earnestly asked Nunn which were currently the best regional theaters in Britain. Spacey, an Anglophile who served as artistic director of the Old Vic for a decade, may well have decided that his future lies here rather than in the United States, but he also knows that, regardless of whether a six-week run as Timon in Manchester, Sheffield or Chichester brings him creative and artistic satisfaction, he faces a near-insurmountable series of obstacles to resuming where he left off when his career imploded spectacularly in 2017.

In truth, even before the actor Anthony Rapp came forward to accuse Spacey of sexually abusing him while he was a minor, Spacey was no longer enjoying the success he once had. Although his performance in Netflix’s House of Cards as the duplicitous politician Frank Underwood met with great acclaim, he had not been offered the major film roles that defined him during the first peak of his fame, between The Usual Suspects and American Beauty. Ironically, and in his eyes tragically, the role that might well have brought him back to prominence — playing the tycoon J. Paul Getty in Ridley Scott’s crime thriller All the Money in the World — saw his scenes cut after the scandal broke, and Spacey replaced by veteran Christopher Plummer, who was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance: Spacey might well have expected to receive the same recognition, perhaps even winning what would have been his third Oscar.

Yet although he has not been entirely absent from the public eye, popping up here and there in Europe and releasing a series of deeply bizarre Christmas videos on YouTube, apparently in character as Underwood, Spacey has not been able to obtain the work he thrived on in the past. With a $31 million judgment against him, obtained by House of Cards producer MRC on the grounds of their losses due to his misconduct during production, he might be forgiven for wanting to make the most of the opportunities he’s offered; before the trial he boasted: “I know that there are people right now who are ready to hire me the moment I am cleared of these charges in London. The second that happens, they’re ready to move forward.”

Yet in the words of his character “Verbal” Kint from The Usual Suspects, “A man can’t change what he is. He can convince anyone he’s someone else, but never himself.” The criminal cases against Spacey have failed, one after the other — a lawyer friend remarked to me that courtroom gossip in London suggested that the prosecution witnesses had been “unimpressive” and easily dismantled by Spacey’s accomplished defense attorney Patrick Gibbs — but there is still a vast amount of scandal attached to his name, whether it was the trial’s revelations of the actor’s casual drug use and promiscuity, the misconduct judgment against him or the fact that, in an industry increasingly wary of hiring anyone who has the slightest hint of an insalubrious private life, Spacey’s closet-skeletons have all come dancing out in public, and the results may not be what he has wanted.

Presumably, Spacey would like to return to the career that he once enjoyed, where he alternated award-winning stage work with well-paid roles in blockbuster films; he could switch between appearing as Lex Luthor in Superman Returns and starring in Eugene O’Neill’s A Moon for the Misbegotten in London and on Broadway. He must look enviously at peers such as Ralph Fiennes and Bryan Cranston who have managed to do exactly that, especially if he notes that he is a double Academy Award-winning actor, and most of his former competitors are not. Yet he is also an intelligent and pragmatic man who knows that the offer to appear in American Beauty 2: Oh, My Beauty is not likely to materialize. Instead, he must make the best of what he has.

During his wilderness period, he made a few films, one of which — the low-budget British thriller Control, in which he has a villainous voice role — is planned for a December release in the US, assuming that a distributor can be found. Yet presumably whatever fee he was paid was nominal, and would barely make a dent in the legal costs that he confessed in court had left him practically ruined.

It would be unsurprising to find Spacey, eager both to act again and to be paid reasonable fees, accepting roles beneath his talent — in undistinguished cheap action films, say, sold to undemanding foreign distributors, and never watched except by the terminally bored or the intoxicated. He would be in distinguished company; the likes of Bruce Willis, John Travolta and Nicolas Cage have all appeared in countless of these present-day B-movies, taking the money and delivering weak dialogue with the air of men who have bills to pay.

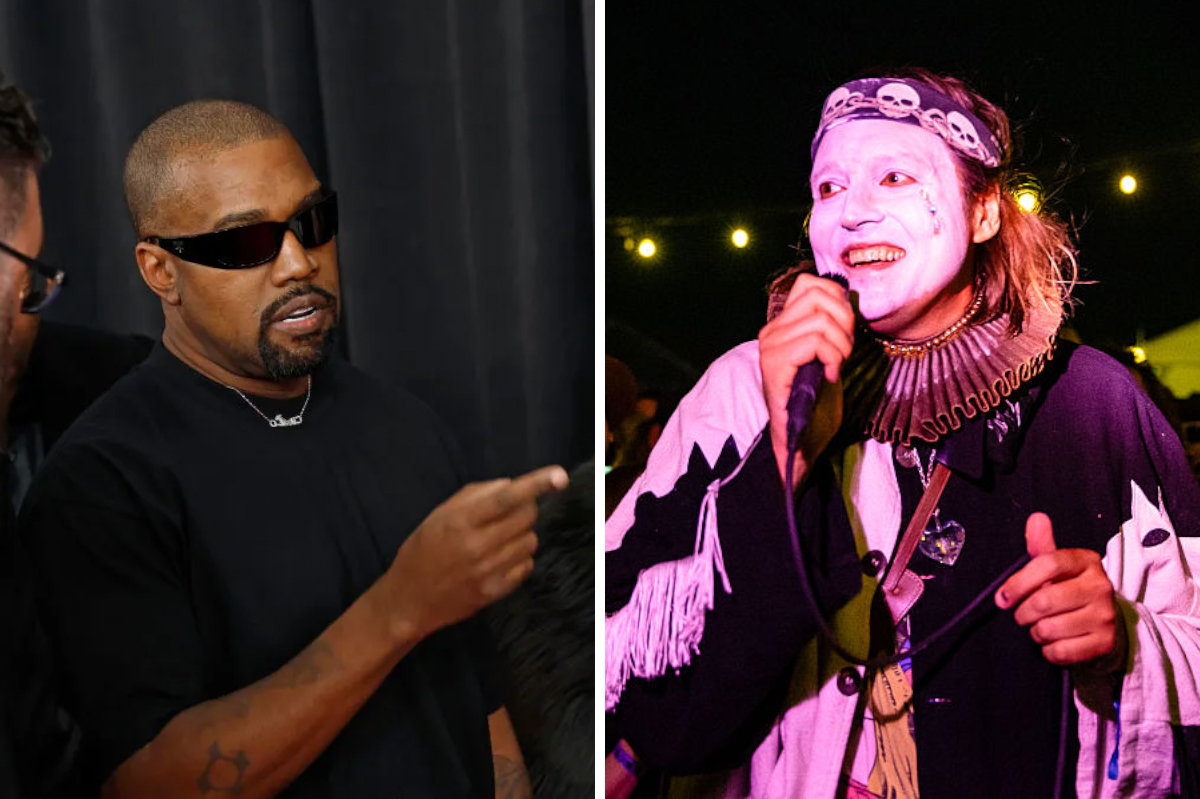

Yet another issue that complicates Spacey’s comeback is that, despite his acquittal in every court he has appeared in, the stain of impropriety still lingers. Armie Hammer, similarly accused but not charged, has seen his acting career vanish altogether, and was last heard of selling timeshares in the Cayman Islands. Johnny Depp — once the most popular and highest-paid actor in Hollywood — has seen his reputation suffer punishing damage thanks to his notorious legal battles with his ex-wife Amber Heard, and although he maintains a loyal fanbase and recently appeared in the Cannes film festival curtain-raiser Jeanne du Barry, has found himself ostracized by Hollywood, a place where he had never felt fully at ease, unlike Spacey, who appeared to thrive on the opportunities and adulation that A-list fame offered him. Yes, that’s Spacey in the famous Ellen de Generes selfie at the Oscars in 2014, grinning away; just over three years later, his career would be in ruins.

It is hard to know what advice to give him: suggesting that he lie low would no doubt bring the riposte that he has done little else for the past six years, and that he wants to resume giving pleasure to millions, on stage and on screen. If a bold filmmaker cast Spacey in a part that channeled his unique skill at combining menace and charm, that could be the beginnings of a concrete comeback; after all, Mel Gibson was canceled by Hollywood twice, returned to direct an Oscar-nominated film and now enjoys a prolific, if undistinguished, acting career in pictures with titles like Confidential Informant and Desperation Road.

Yet Spacey, who has never struck interviewers or colleagues as doubting his own abilities, is unlikely to want to waste his time in roles he would perceive as beneath him. A stage comeback is more likely, but even this is problematic; one can imagine earnest, politically engaged stage crew simply refusing to work with him — as happened with the director Terry Gilliam a couple of years ago at Spacey’s old haunt, the Old Vic. That might end up being hugely embarrassing for all concerned.

Yet one source of comfort that he can cling to is that he remains a major figure in popular consciousness. An account of his dinner with Nunn made it into several British newspapers the following day, and his trial was covered by the international media with great enthusiasm. Spacey is not going to disappear into the shadows quietly; he will rage against the dying of the kliegs for the rest of his life. Still, it might be worth his while remembering Timon’s declaration: “Timon will to the woods, where he shall find/Th’unkindest beast more kinder than mankind.” Hollywood loves a comeback story, but only time will tell if Spacey will be allowed to have his.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2023 World edition.