doesn’t have a world-class philosopher (Kierkegaard was Danish). Karl Ove Knausgaard declared at the end of his previous book that he is no longer a writer, and it looks as though he’s moving in to fill that space. A very modern space: a selfie space. Nietzsche observed that all philosophy is autobiography, and Knausgaard certainly qualifies, having written 4,000 pages of a multi-volume autobiography called My Struggle.

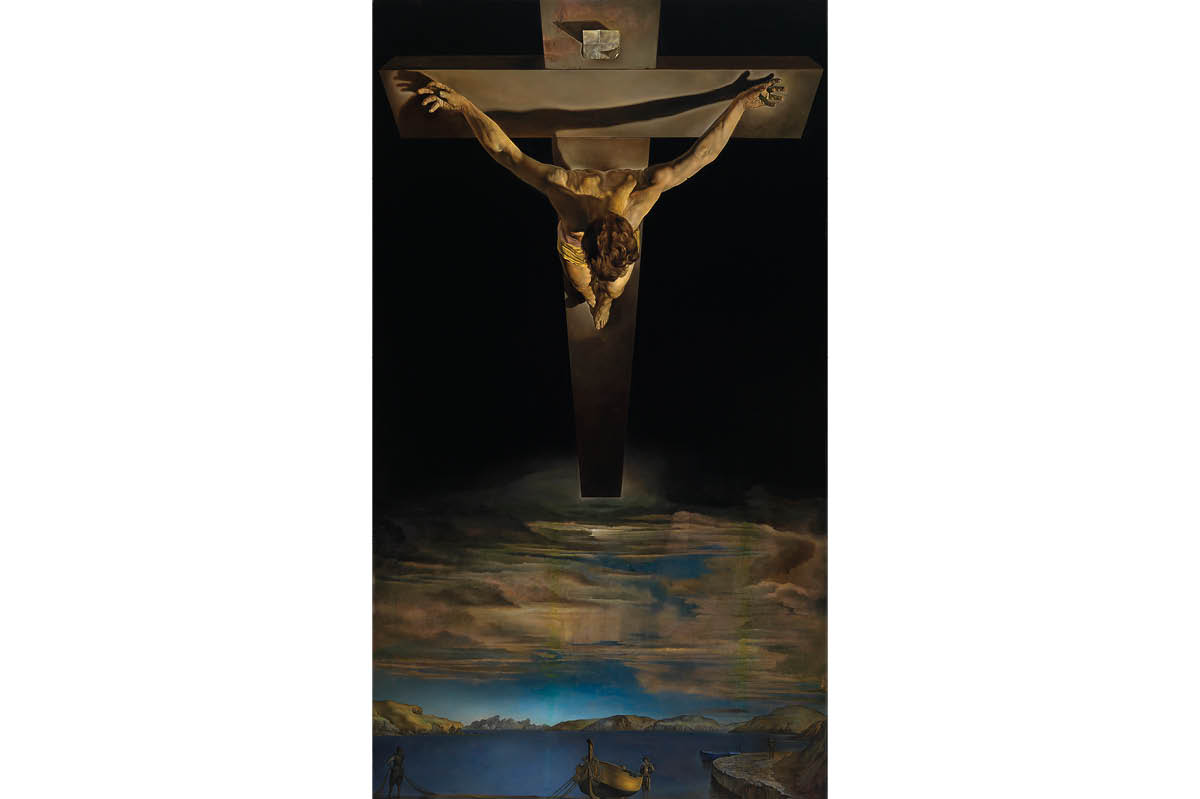

Now he has given us a book on Edvard Munch, the Norwegian artist best known for painting ‘The Scream’. Munch wrote an almost Knausgaardian number of autobiographical pages in his private journals while recording the outer reality of his life in hundreds of self-portraits. Both men operate on the principle that scrupulous self-examination is the only way of arriving at some sort of universal truth.

‘My art is self-confession. Through it I seek to clarify my relationship with the world. This could also be called egotism. However, I have always thought and felt that my art might help others to clarify their own search for truth.’

Who wrote that? Munch or Knausgaard?

With Knausgaard’s book on Munch, we enter the realm of biography written by the doppelgänger. These two handsome, brilliant, wildly solitary, introverted Norwegians feel compelled to bare their souls publicly in their art while neurotically guarding their personal privacy. Ibsen was the same.

The self-effacement of the artist seems to be vital to the psyche of the creative Norwegian giant. What he produces for public consumption really is the tiny tip of the massive submerged iceberg, the bit of the self that he’s prepared to show us.

So Much Longing in So Little Space was first published two years ago in Norwegian. Now it’s translated in time for the current exhibition at the British Museum, curated by Giulia Bartrum (Edvard Munch: Love and Angst, until July 21). Knausgaard can’t help writing about his experiences, and this book is his response to being invited to curate an exhibition of Munch’s work in Oslo in 2017. The book is part justification, part apology for his choice of pictures. He’s charmingly insecure about the 143 works he selects from the hundreds of ‘basement drudges’ that lurk unseen in the bowels of the Munch Museum.

When you are asked to do a huge thing like curate a public show, you can’t put the whole reason for your choices on the walls — so why not write a book? A show is an ephemeral thing and we are reading a book relating to something we’ll never see. Its illustrations are pretty inadequate and irritatingly uncaptioned. Unless you can physically reconstruct the Oslo show, So Much Longing in So Little Space is of little value except as a philosophical meditation on the nature of art and the self. A pretty huge exception. Unmoored from the show, the book takes off.

Knausgaard’s omission of ‘The Scream’ from the exhibition makes it the elephant in the room. It asks the question that we all want to ask and that Knausgaard is uniquely qualified to answer: once you have created a cultural icon, what comes next? What do you do when more introspection no longer yields deeper insight? Have you exhausted your self as your own anatomical testing ground?

Munch painted four ‘Screams’. Similarly, Knausgaard’s Struggle revisits the death of his father repeatedly. Can you move on after you have described the central experience of your life completely truthfully, Knausgaard worries. Must every creative artist share the dreadful fate of the wrinkly octogenarian rock star forever re-enacting a moment that once was true? Does the creation of something enormous condemn you to Nietzsche’s ghastly Eternal Recurrence: to a lifetime of self-plagiarism?

Self-plagiarism? He’s on a riff. And Knausgaard on a riff is delicious. Both his and Munch’s art is based on plagiarizing lives, their own and others’. But if you’re a writer, the worst crime you can commit is plagiarism. It gets you drummed out of the Brownies. Yet, he muses naively, newspapers all write the same story. And in the art world, they don’t call it plagiarism; they call it ‘influence’. That’s how the whole art-history curriculum organizes that enormous baggy thing called art: by tracing lines of ‘influence’ that eventually lead to such absurd events as some punter paying £1.5 million for a Warhol interpretation of Munch’s ‘Scream’.

What constitutes an enduring work of art? What is contemporary, what is eternal? Will Knausgaard, like Munch, make the posterity cut? The problem of untangling eternal fame from 15-minute fame, he mulls, is that the tone of the time goes unnoticed by its contemporaries:

‘Everyone belongs to the time in which the artist has created the work. It is the zeitgeist. But a poor work of art will express only this. After some years it will be seen only as an historic document.’

There is

‘an ironic dimension to our perceptions of the history of art and literature… only those works that break with the era come to be seen as typical of the era… by expressing their own self, they speak to what we have in common.’

Great works of art transcend time and space. Munch lived a long time. He died at 80, 50 years after creating ‘The Scream’. Following his big revelatory moment, he never stagnated artistically or intellectually. In fact, he found life even more interesting on the other side of his big existential crisis. He was drawn to find the significant in the insignificant, in the common motifs that we all see all the time, every day.

In his Munch exhibition in Oslo, Knausgaard chose to fill a whole section with pictures that Munch had painted of trees. Just trees. The tree room was the equivalent of the many school runs that Knausgaard describes in his autobiographies. At one point he quotes Karen Blixen saying, ‘You can’t go chasing the kingdom of heaven with a pram’, but this is exactly what Munch’s post-‘Scream’ paintings and Knausgaard’s post-Struggle thoughts are about. The very nature of the big, revelatory moment is transitory. Nobody can live in it very long. Once you’ve gazed into the abyss, the way forward lies in discovering that there is equal value in the truth of the ordinary. Go push that pram.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.