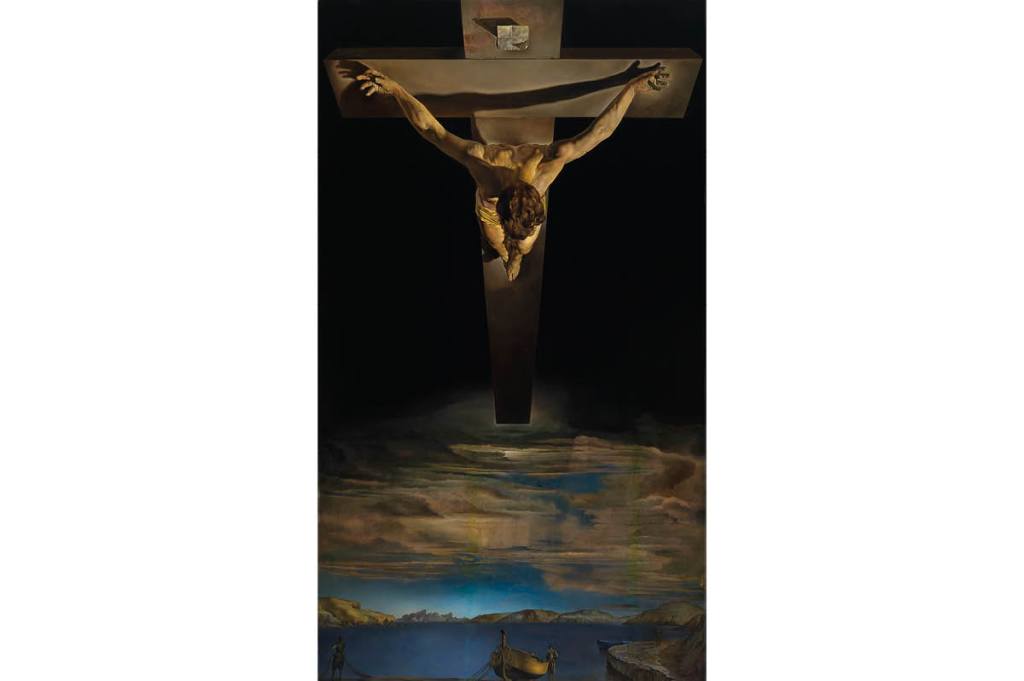

I arrived in the city of Figueres early one January morning to visit one of the most popular, and bizarre, art museums in the world, the Teatre-Museu Gala Salvador Dalí. It houses a dreamlike picture that, for the first time since it left over seventy years ago, has made a temporary return journey to Spain. Originally simply titled “The Christ,” the 1951 canvas depicting the giant figure of a man on a cross, shown at an overhead angle hovering over a moody seascape, was painted by the most famous son of Figueres, Salvador Dalí. Through April 30, it forms the centerpiece of a show exploring its creation, history, local connections and symbolism.

Housed in the town’s former theater and significantly expanded under the artist’s direction, those who have visited know that, like the Surrealist who founded it, the museum can be a seemingly inscrutable place to navigate. There was a deliberate intent here not to create a chronological, forced path to follow. Rather, the immersive experience of wandering about the complex is brilliant, confusing and at times off-putting, much like the unusual mind of Dalí himself. Fortunately, the setting designed for the visit of Dalí’s most famous religious painting is much more rational and informative than its creator’s often inscrutable voyages into the subconscious.

I was greeted by director Montse Agueri Teixidor, head of the three local Dalí museums and Imma Parada, director of communications and protocol. Aguer noted that the picture has caused something of a sensation ever since its arrival. “We have had visitors deeply moved by seeing this image,” she explained. “Some people hate it. Some people have stood and wept before it. It’s a very powerful piece.”

Before seeing the work itself we passed through a series of rooms that build up to the main event. With a sense of theatricality befitting its founder, the museum chose to raise the level of drama by denying the instant payoff of peeping into a space and seeing the star attraction at first go. One is initially treated to Dalí’s beautiful “Basket of Bread” (1945), whose tones and forms prefigure elements of the “Christ.” The still life is housed in a sumptuous Baroque frame chosen by the artist’s wife, Gala — as Parada explained, throughout the museum many of the artist’s works are displayed in gorgeous antique frames chosen to reflect the connection that Dalí wanted to make between himself and the Old Master painters whom he admired.

Subsequently we examined ephemeral treasures that any art nerd would swoon over. There was a Dalí sketchbook lent from a private collection, showing some of the preparatory ideas for the painting, and digitized so that the visitor can turn the pages without handling them. Research revealed the origins of the figures of the fishermen that appear at the bottom of the picture, taken from sketches by Velázquez and Le Nain, and found in an art history book owned by the artist. And there were photographs and drawings of Hollywood stuntman Ross Saunders, who posed for the figure of Christ suspended from a ceiling so that the artist could study the effect of gravity on the muscles of the human body.

Later, we paused to discuss a remarkable video installation mounted on giant curved screens. Its slides compare other famous representations of Christ Crucified and the Dalí version, with particular emphasis on the painting known simply as the “Christ of Velázquez” in the Prado. Details of Dalí’s drawings show how carefully he considered the composition, including eschewing the traditional elements of nails or the crown of thorns, and the decision to focus on the beauty of the figure of Jesus. “My principal preoccupation,” he notes in one of the slides, “was that my Christ would be as beautiful as the God that He is.”

Finally, we made a left turn into a darkened room with a black and white checkerboard floor ringed with red velvet curtains, and entered a kind of hushed and meditative atmosphere as we approached the work I had come thousands of miles to see. It’s an image that has been with me my entire life, since my parents had a large print of it in the playroom at home, and when that eventually disintegrated another print found its way into their bedroom.

The title by which the painting is generally known is “Christ of St. John of the Cross,” which gives us part of the story of its conception. St. John of the Cross (1542-91) was a Spanish mystic best known, even to non-Christian audiences, for his lengthy spiritual poem, “The Dark Night of the Soul.” The Carmelite friar had a vision of the crucified Christ which he put down in a sketch, and Dalí maintained that, after seeing the drawing, he had his own mystical dream in which he felt compelled to paint the image. Some art historians pooh-pooh this explanation, since Dalí was often inconsistent when explaining his work, and as the exhibition demonstrates, Dalí had been thinking about creating this image for quite some time.

The painting is referred to in the Figueres exhibition not by its more familiar name, but as the “Christ of Portlligat.” I asked Aguer about the decision to use this very unusual title, since it is not what Dalí himself titled the piece nor the name by which it is best known. “We wanted to make that connection to Portlligat,” she explained, “because for so many people they don’t realize that the seascape that appears in the picture is a real place, in this area, and not something that Dalí just dreamed up out of his imagination.”

I was joined by Fèlix Roca Batllori, general manager of the museum. We talked about how arguably the two most well-known depictions of the Crucifixion in art are by Spanish painters. Roca explained how in his interpretation, Dalí was not only taken with St. John of the Cross’s sketch, and led by his own dreams, but wanted to emulate the great Spanish Golden Age painters, above all Velázquez.

Given that background, with a Castilian saint and an Andalusian artist having influenced the Catalan painter’s work, I asked whether we should consider the “Christ” a Spanish painting, or a Catalan painting — because there is a difference. Roca paused for a moment before responding, “It’s neither. It’s an Empordà painting.” He then suggested a trip to the “ceiling,” Dalí’s bedroom in the “Palace of the Winds” section of the museum, where the artist himself lived.

The scene painted on the walls and ceiling of the room depicts a technicolor dreamscape featuring Dalí and Gala ascending to heaven, a colossal work which the artist executed after his wife’s death. Roca pointed out that much of the countryside in the picture is of Catalonia’s Empordà region. By incorporating local landscape elements into his paintings, Roca suggested, Dali was paying homage to the place of his birth, even though he had spent many years living a peripatetic existence, traveling to places like Los Angeles, New York and Paris for long periods of time.

Whatever its local connection, ultimately Dalí’s “Christ” is much more than a regional image; otherwise it’s doubtful it would hold such broad appeal globally, including among those who have never been to the Empordà. Dalí’s switch from more abstract explorations of the subconscious to wrestling with questions of faith remains, in the eyes of many art historians, a serious mistake. For his part, Roca thinks that at this time in his life Dalí was trying to come to terms with who he was and what he believed. “I think that Dalí was truly, sincerely looking for God,” Roca says, “but had a difficult time finding Him.”

I returned to the “Christ” alone, to decide for myself what I thought of it. I stood back in a darkened corner of the room, so that I could watch unobserved. A steady stream of visitors passed through the chapel-like space; there were speakers of Catalan, English, French, Korean, Spanish and other languages I did not recognize. On entering the room, all fell silent, and if they did eventually say anything to their neighbors, they did so in hushed, respectful tones. Some approached quite close to the canvas; others stood further back and just took it all in.

I was about to leave the gallery myself when the neighboring Romanesque parish church of Saint Peter began to toll the Angelus. Finding myself completely alone with the painting for a few minutes, I went and stood in the center of the room. As the bells tolled this ancient prayer of the Church, which concludes with a petition that we may, “by His Passion and Cross, be brought to the glory of His Resurrection,” I concluded that, for me at least, whatever elements of dreams, self-promotion, competition with the Old Masters or local pride that Dalí worked into this picture, it is also the work of a man of faith. In his imperfect, weird way, Dalí was trying to understand something that is perfect, something that represents pure love, something so deeply beautiful in itself, mere created beings cannot fully grasp it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply