Karl Lagerfeld was an icon when he died in 2019, but for most of his career he was unknown outside the fashion business. He was born in 1933, the year Hitler came to power, a distasteful coincidence, so Lagerfeld altered his birth to 1938. He was an only child, whose father did well by introducing condensed milk into Germany. His parents had been Nazi members, and Karl saw his future elsewhere. At eighteen he left Hamburg for Paris. Short and chunky, he had simian good looks, with beetling brow and a smile that was wider than his eyes; and he didn’t want for admirers. In 1954 he won the young designers Woolmark Prize, but only in “the coat category.” The winner in the more prestigious “dress category” was the several-years-younger Yves Saint Laurent — and that scorched Karl for life.

Unlike Saint Laurent, Lagerfeld worked mostly for other houses, and simultaneously. He turned Chloé, Fendi and Chanel into global, off-the-peg money-spinners, making himself fortunes in the process. He entered the mass market with H&M and his own label. He gave spectacular promotional banquets. To favored contacts he sent colossal bouquets from the most expensive florists — his annual spend at Lachaume alone, in Paris, was one and a half million euros. His personal life, too, gluttonized on consumerism. He bought countless houses in obvious places, and renovated them in eighteenth-century, Art Deco or modern styles, sold up and repeated the process. He moved in Rolls-Royces, private jets and boats, and halted in deluxe hotels.

His social circle was narrow: celebrities, fashionista-aristos, models, interior decorators and young gay men. He fell in love once, with one of the most tiresome gays in the Parisian monde, who repaid the compliment by sleeping with Saint Laurent. That wasn’t surprising, since Lagerfeld never had sex with anyone and repeatedly said so. William Middleton has researched the matter and says it’s true, after his youth. Instead, the couturier would pleasure himself in solitude, watching the videos of Jean-Noel René Clair, a pornographer who filmed soldiers and street lads from around the world. When this also became too much bother, Karl acquired a cat which he pampered wantonly.

The engine for all this was his fashion shows, with their clunky sets and cheesy music (Chaka Khan, Elton John, Kraftwerk). At Lagerfeld’s height he was designing fifteen major collections a year. Much, perhaps most, of this biography is devoted to detailed descriptions of these, in “wow amazing” prose that quickly palls. The business involved a huge amount of backroom work; and it testifies to Lagerfeld’s fine treatment of his workers that he was able to sustain a rising trajectory over so many decades. The clothes were derivative but popular. His best work is the simplest, especially the riffs on the classic Chanel suit. The moment he went froufrou, it became incontinent.

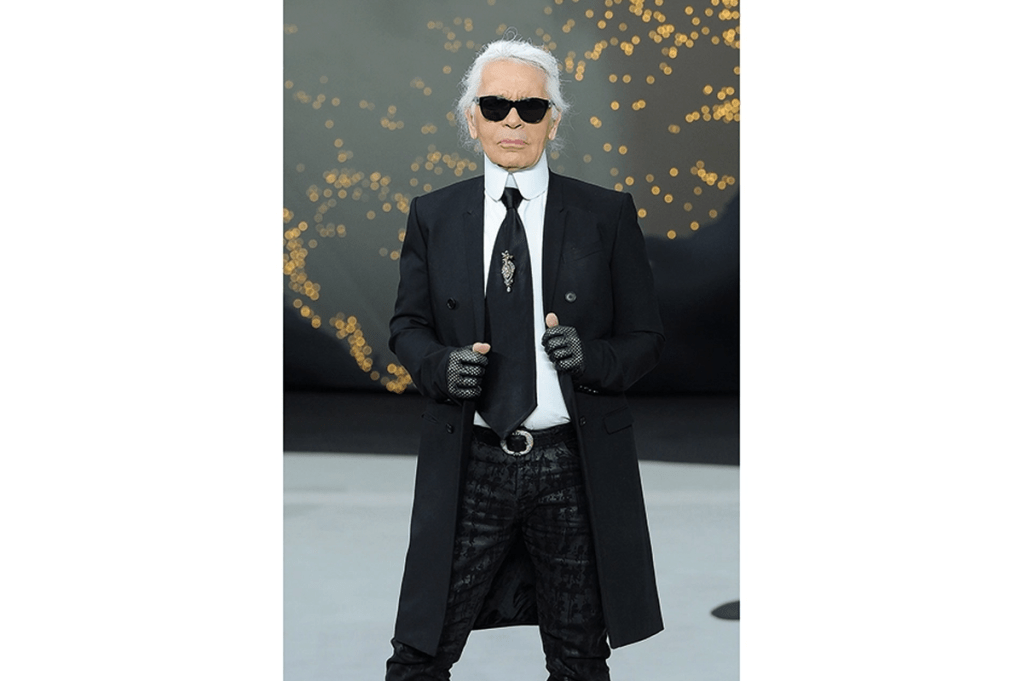

Then the great day arrived. Saint Laurent retired in 2002. Even better, he died six years later. At last, Karl could step forward into the international spotlight as Mr. Paris Fashion. To facilitate this he developed a carapace, filched from Vivienne Westwood, to make himself immediately recognizable wherever he went. It was hideous, topped by sunglasses and white powdered hair in a tight ponytail that would be a beacon at public events (Warhol’s idea). He became brilliant in interview, with a gift for astringent repartee, a couturier with a mind. The skin-tight trousers revealed bandy legs, but what the hell, it worked: he put his own collections in the shade entirely. When you consider the names Worth, Poiret, Chanel, Dior, Quant, Saint Laurent and Westwood, countless images of their transformative apparel rise up in the mind. With the name Karl Lagerfeld there is only one image, the grotesque costume he adopted in later life. His career made no mark on fashion itself, only on the fashion business.

At his death Sotheby’s sold everything. Unlike the legacy of Saint Laurent, there is no Karl Lagerfeld Foundation or museum; and as far as I’m aware there are no plans for any. Some of his homes, especially in Paris, Monaco and Hamburg, were exceptional; and he was in a position to set them up as important cultural attractions. If only for this, he deserves to be remembered — that at the epicenter of an acquisitive society he chose to travel light. He often said that he hadn’t the slightest concern for posterity and was interested in living for the moment. Pose or not, posterity has respected his wish. All has gone, like the bubbles in Champagne. In its way — wonderful.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.