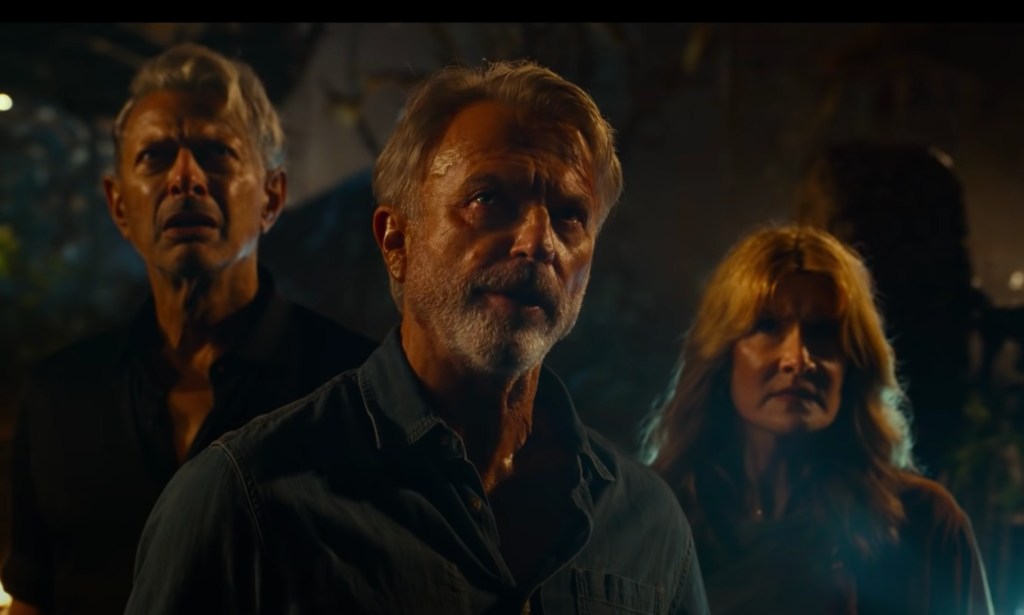

The third — and apparently final, if rumors are to be believed — Jurassic Park film arrived in American theaters last weekend. Entitled Jurassic World: Dominion, one of those meaningless names that looks good on a poster, it was released to critical scorn: “the last time dinosaurs were subjected to a disaster this bad, an asteroid was involved” was a typical comment.

Although Dominion opened to a mighty $145 million at the box office, terrible word of mouth is likely to see the gross plummet before very long. This is very much not a Top Gun: Maverick situation, where the most unlikely people have found themselves raving about a brilliant film. This is a bad, generic summer blockbuster, and it will be forgotten in due course, like all bad, generic summer blockbusters.

Nearly thirty years after Steven Spielberg’s first Jurassic Park film, and thirty-two years after Michael Crichton’s original novel was published, the idea of dinosaurs roaming amongst us remains a seductive one, both for filmmakers and audiences. Crichton’s book posited the same basic idea as his 1973 film Westworld, both of which drew heavily upon Frankenstein: just because humanity can create something hitherto unimaginable does not mean that it should. It’s significant that Spielberg’s adaptation changed the character of John Hammond, the billionaire founder of the project that created the dinosaurs, from a cold, Machiavellian cynic in the novel to a warm, if misguided, visionary. Appropriately, of course, he was played by Richard Attenborough in full twinkly-eyed mode.

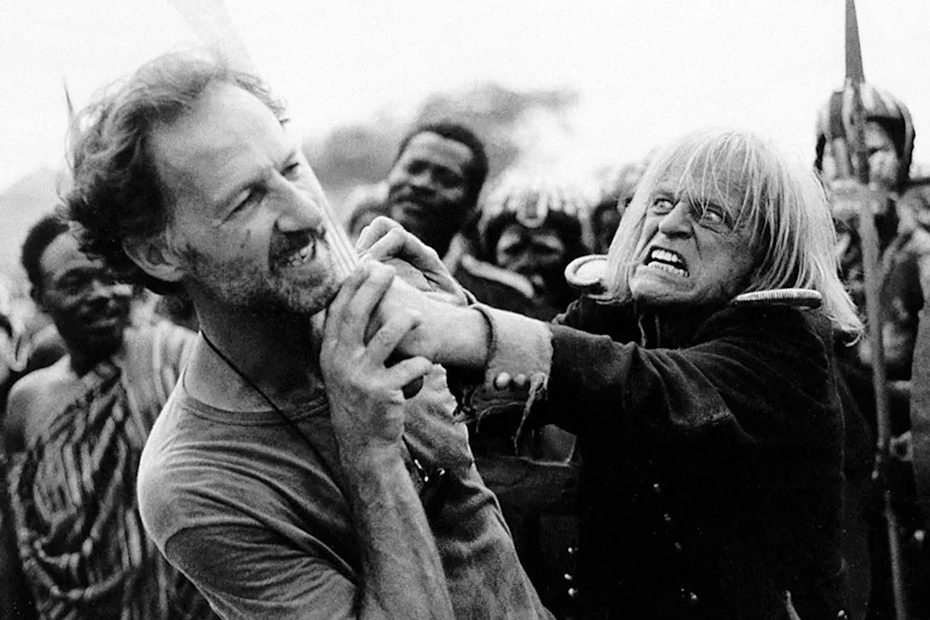

Yet where Spielberg’s original film succeeded so admirably was in its mixture of suspense and awe. It is not for nothing that John Williams’ main theme — as adapted in the new movies by Michael Giacchino — is a soaring testament to grandeur and wonder, rather than the suspense-laden motif of Jaws. And the dinosaurs are shown a suitable level of respect, rather than being treated as the vicious predators that they might have been in another film. By the time Spielberg made an inferior sequel, 1997’s The Lost World, there was a widespread expectation that he would copy James Cameron’s template with Aliens. But those hoping for intense action scenes of man versus T-Rex were to be sorely disappointed: these dinosaurs remained the true kings, untouched by the hand of man.

Spielberg’s films did, at least, have both wit and intellectual achievement on their side. The Jurassic World trilogy, largely overseen by the director Colin Trevorrow, has been an exercise in pointlessness. The films have attempted to mix the usual dino-action porn (“see how the monsters eat members of the supporting cast!”) with more conventional stunts that seem designed to flaunt its star Chris Pratt’s unlikely status as an action hero. Dominion therefore features an incomprehensible motorcycle chase through Malta that looked exciting in the trailers and makes no sense on screen, alongside scenes of corporate skullduggery that are about as appealing as attending a Jeff Bezos board meeting. There is no philosophical point to the films other than dinosaurs = chaos. Only the most committed of dinophiles could really enjoy these shenanigans.

When Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein, which she subtitled “The Modern Prometheus,” she suggested in her prologue to the revised 1831 edition that her intention was “to think of a story…one which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature, and awaken thrilling horror—one to make the reader dread to look round, to curdle the blood, and quicken the beatings of the heart.”

It was with this edict in mind that Crichton wrote his novel, but the central Faustian idea of man overreaching himself has long since been forgotten. Instead, we have a riot of pixel-heavy special effects and deafening noise, which — to quote Macbeth — is “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” Let us hope the computer-animated dinosaurs now find their asteroid, and do not trouble our movie screens again.