One of the saddest things about popular music is the talents it can’t accommodate. Robbie Robertson, of the Band and much else besides, died in August at the age of eighty, and never found a proper home for his gifts after that great initial burst of late-1960s creativity.

But at least Robertson was widely recognized by his peers as one of the outstanding electric guitar players of his time, although the contemporary guitarist he most admired himself was Jerry Miller, of the group Moby Grape. Unlike Robertson, Miller, who’s happily still with us today, hasn’t as yet won a Grammy, or been inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. But he did play a starring part in what’s surely one of the great show business morality tales of its time.

Born into a working-class family in Tacoma, Washington, Miller wandered into a local music store one afternoon and heard the great jazz guitarist Wes Montgomery playing over the speakers. “I want to do that,” he thought. And soon enough, having sold his secondhand Chevy to buy a customized Gibson L-5 guitar he named Beulah, he was. Miller subsequently found himself among many of the giants of the classic rock era — swapping guitar tips with Eric Clapton, hanging out with the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane, sharing cocktails with Janis Joplin and chatting with Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones as the latter floated around the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival in a pink boa.

Moby Grape began life after Miller and his other great Northwest friend Don Stevenson, a singing drummer, relocated to San Francisco in the mid-Sixties. Actually, there were two such migrations — the first lasted only a couple of weeks. “We hit town on the very day the first topless bars became legal there,” says Miller, today a trim, gray-bearded grandfather with drowsy eyes and an engaging chuckle. “You can imagine the sort of joints we were playing. All the drummers were doing these ba-boom beats in time to the girls’ clothes coming off.” Nice as that was, Miller needed to make a living. Within a year, he and Stevenson had hooked up with multi-instrumentalist Alex “Skip” Spence, bass player Bob Mosley and another guitarist named Peter Lewis. “It sort of evolved over time,” Miller reflects. “One night we were playing a dive in Belmont, just south of San Francisco, and a guy about my age with dark curly hair, a goatee and granny glasses came up and introduced himself as Jerry Garcia. He said he dug our sound, and that we should crash out for a while with him and his buddies, the guys who became the Grateful Dead. So we did. Things like that seemed to happen in the Sixties.” Pretty soon the new group had grown their hair, ditched their uniforms and taken the name Moby Grape, after the punchline of the absurdist joke about what’s purple and floats in the sea; their music could be described as country rock, with a dash of psychedelia. “We knew we were pretty hot,” says Miller, for once casting modesty aside. “I can remember driving home after the first time we all played together and feeling so happy I was singing ‘I’m Into Something Good.’”

And for a while he was, too. “We started making a little money, and Don and I were renting this twelve-roomed place with a pool down in San Carlo for $199 a month,” Miller recalls. Nobody in the band really talked about hard drugs in those days, although the Grape undeniably got about a fifty-year head start on the eventual legalization of recreational pot in California.

Before long, management had appeared on the scene. Certain interested parties are still with us, so perhaps it’s best to be brief and merely say that there was some small misunderstanding between the young musicians and the individual to whom they entrusted their affairs; it later transpired that the contract they casually signed one night gave him, not them, ownership of both the group’s name and their songs.

By early 1967, Miller and his colleagues were working on the material that became their first, self-titled album. One evening that spring, he had the melancholy job of driving his wife Sherille back to the downtown Greyhound station so she could take the bus home to Tacoma. “After I dropped her I asked this guy what time it was, and he told me it was 8:05. A few minutes later I was driving over the Golden Gate Bridge, half thinking of throwing myself off it, I was so sad, when this tune suddenly came to me.”

When Miller got back to the pad in San Carlo he asked Don Stevenson to help him finish the song, which, logically, they called “8:05”. It bears comparison to any of the all-time great busted-heart country ballads and was one of the standout tracks on Moby Grape’s freshman album that June. The record is still regarded as a classic, and regularly appears in Rolling Stone magazine’s incessant “greatest ever” lists. The whole album only lasts thirty minutes, but then half an hour of the Grape was worth at least a night of almost any other band.

After that, a combination of bad advice, bad breaks and bad behavior under mined a group we might otherwise think of today in the same terms as a more musically adept version of U2 or the Eagles.

“Skip Spence had seen Hendrix smashing up his equipment on stage, and he thought he might like to try it himself,” Miller remembers. “Unfortunately, the first place he chose to do so was a Catholic church hall in Milwaukee, which wasn’t quite ready for the sight of a wild-eyed guy with long hair ramming his guitar into the amplifiers. There was an almighty explosion, and some sparks shot up the back of the stage. Someone yelled out that we were going to burn the place down with everybody inside it, and someone else called the cops. Things went downhill pretty quickly from there, and we left in a hurry.”

As the band members ran for their waiting limousine, a Milwaukee police officer appeared and chased on foot behind them. “Somehow, this poor guy got his arm stuck in the car door, and he had to jog alongside us for a while before he could get free. Very bitter about it, he was. I can still remember the look on the priest’s face as he stood there watching this whole circus speed away from his church.”

In time, the Grape gave a somewhat more extended performance in front of an estimated 30,000-strong audience at the Monterey Pop Festival, which among other things reunited Miller with his hometown friend Jimmy (by then “Jimi”) Hendrix.

“We sat there after the show, talking about the old days,” Miller says. “‘Is the Tiki Club still going?’ and, ‘Whatever ha pened to so-and-so?’ That kind of thing. Of course, Hendrix had moved on a bit by then. What I mainly remember are these lines of women coming backstage to get his autograph, and instead of the traditional album or photo they were all asking him to sign their bare chests. It was weird because there wasn’t a flicker of emotion by Jimi in the whole transaction. It was like it was just one of those things bound to happen in show business.” Miller himself took the whole Monterey scene, and the Grape’s first flush of success, similarly in stride. “It wasn’t until years later that I went, ‘Wow. What happened there?’”

That summer of 1967 proved to be Moby Grape’s finest hour. They should have consolidated their progress, but within only a year or two it was effectively all over. Music is a superstar business, and it can be cruel on those just outside the charmed circle, particularly for a band collapsing under plummeting record sales and rampant financial piracy. And the drugs probably didn’t help, either.

“Skip Spence disappeared from our hotel in New York one night,” Miller says, “and whatever happened to him he came back a completely changed character.” From then on, Spence seemed to oscillate between sudden moments of violence and others when he expressed a hippyish desire to give the group’s modest royalties away (a sentiment not shared by his bandmates). It proved to be the start of a tragically irreversible decline. The prodigiously talented Spence, diagnosed with schizophrenia, lived much of the rest of his life in mental institutions and died in 1999, aged fifty-two.

“We wanted to keep going,” says Miller. “But we kept hearing the same thing. All the big festival promoters wanted the original five, and when Skip left, the bookings just tailed off.” Moby Grape’s last studio album featuring the classic lineup was 1971’s 20 Granite Creek, which won widespread criti- cal acclaim but sold about as tenth as many copies as the band’s debut. “We could have had it all, but we ended up with pretty well nothing.”

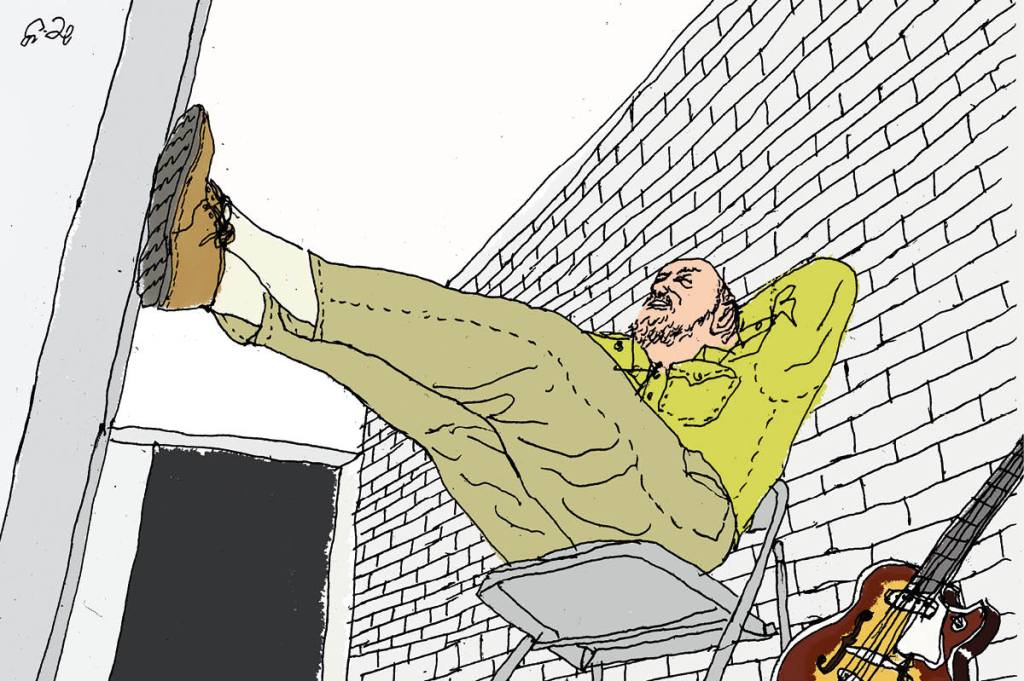

Miller still resides in Tacoma today, just a few miles from where he grew up, in a house he shares with his vivacious companion Jo Johnson, their small but full-throated dog Kahlua and the ever-present Beulah. Certain other rock-guitar gods of Miller’s vintage may live in mansions made out of Cartier jewelry and swim in pools filled with Cristal Champagne and pink ice cubes, but there’s little of that in evidence at his modest suburban home, with its slightly rickety metal gate and the rusting Acura sitting in the tall grass in the back yard.

“The way I see it, I’m the luckiest guy in the world,” Miller announces, as he pads around the place in his jeans and well-scuffed cowboy boots. “I’ve still got my health and my music, and I still get to do what I most love for a living. Maybe the Grape were screwed, but so what? If you haven’t been ripped off, you haven’t been in the music business,” he adds, with a contemplative puff of his cigarette, his equanimity surely the model of what every old rocker might hope to display in similar circumstances. Perhaps, in the end, he’s just too damn nice ever to have made an effective rock star.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply