Relatively few rock musicians would care to replace Eric Clapton in a band, or to veer spectacularly off course to record a free-form jazz-inflected album that defied prediction to sell two million copies, or for that matter to laughingly turn down an invitation to become a fully fledged member of the Rolling Stones.

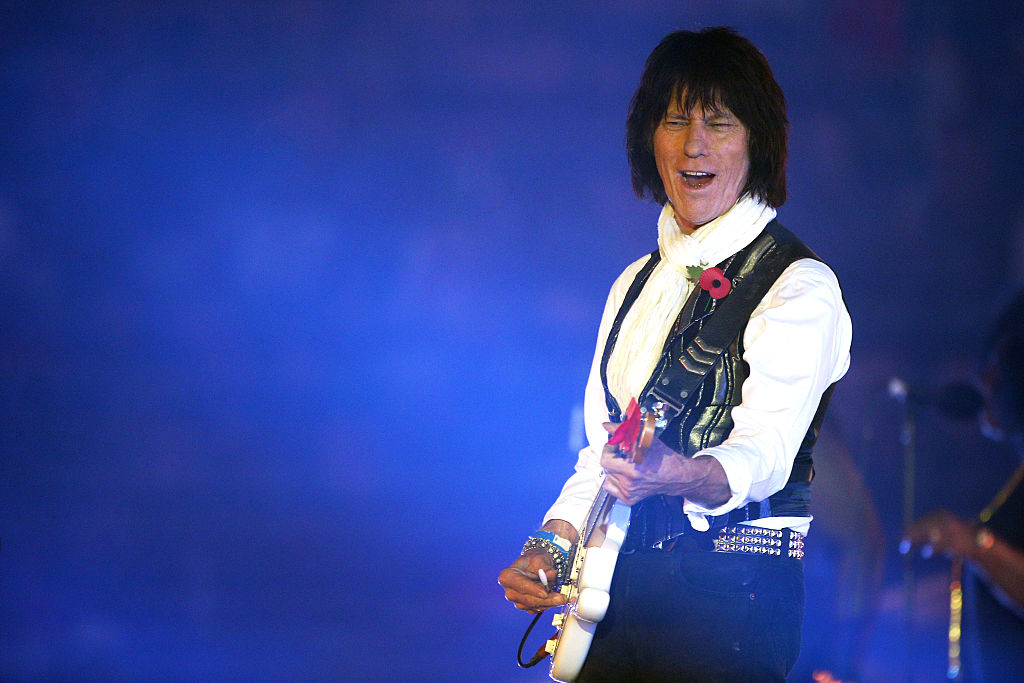

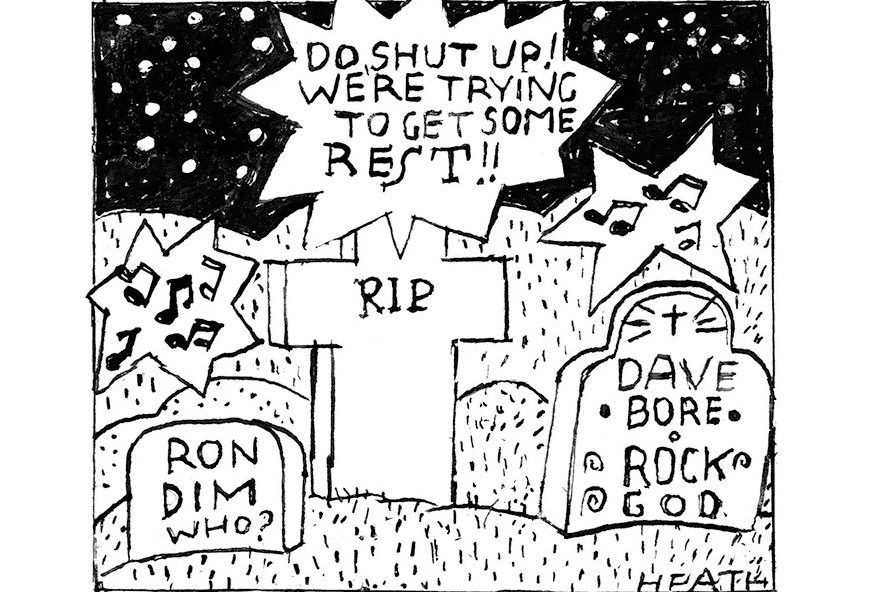

The British guitarist Jeff Beck, who died this week at the age of 78, did all of these things and more. A brilliantly gifted instrumentalist, he never kept still musically. To call Beck the David Bowie of the guitar world would be to confer a somewhat misleading sense of consistency on a maverick who seemed to reinvent himself with every album, and sometimes every song.

It took me many years to discover just how good Beck was, a shameful admission for a pop nostalgia writer. The problem, of course, was that I was blinded to his talent by his musical contrariness, the occasional excess, and his somewhat bizarre penchant for wearing shiny white go-go boots and sleeveless jackets. I was also too young to have been there in his early prime, or to have listened to his great early records like 1968’s Truth, with Rod Stewart on vocals, when they pretty much broke the mold of everything that had previously been understood about popular guitar music.

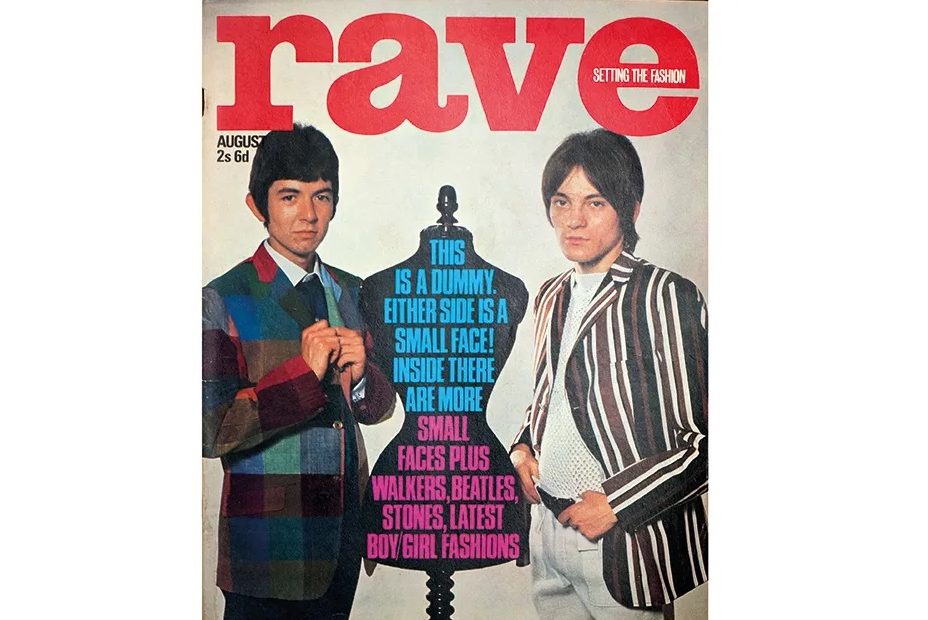

Emerging from the British art school scene of the early 1960s, Beck first joined the Yardbirds, instantly transforming them from slightly earnest suburban mimics of American blues into a band with a progressive edge that included otherworldly, sitar-like guitar solos, among a host of other weirdly insinuating effects that ran the gamut from the sound of the factory bench-press to Gregorian chanting. Beck did all that. With him in their ranks, the Yardbirds achieved the seemingly impossible and actually became cool. That led Michelangelo Antonioni to cast them as the house band in his sardonic salute to Swinging London, 1966’s Blow Up.

“Jeff was on another planet to us,” the Yardbirds’ Chris Dreja once told me. “Totally unique, a master of organized chaos, utterly impossible to pigeonhole.” And something of a handful while on the road, by all accounts. Beck was not happy about some of the constraints of the typical budget-conscious rock tour of the 1960s. His frustrations on the matter came to a boil one night in Dallas, where those who witnessed the guitarist’s fury both onstage and in the dressing room afterward long spoke of it in hushed tones, like old salts recalling a historic hurricane. Beck and the Yardbirds parted company shortly afterward.

And that pretty well established the template for his whole later career. Beck was a one-off, with an imagination and flair beyond that of any other contemporary guitar player, not excluding Jimi Hendrix. But he wasn’t one to succumb to the demands of playlist-pleasing, box-ticking blandness. When his friends Led Zeppelin made it big in the late 1960s, Beck insisted he was quite happy where he was. “I personally couldn’t put up with that mass adulation,” he said. While many lesser musicians later appeared at 1985’s Live Aid, Beck preferred to stay home in the English countryside and tinker with his collection of hot-rod cars. “I didn’t want to go, because I hate large crowds,” he noted.

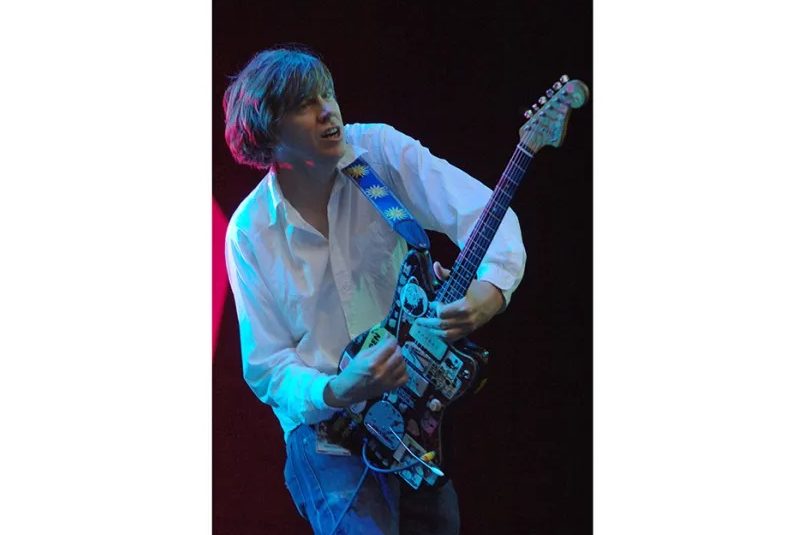

For all that, Beck wasn’t completely shunned by the mainstream. He won eight Grammys and was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame twice, as a member of the Yardbirds in 1992 (“They kicked me out… fuck them!” he announced at the glittering award ceremony), and as a solo artist in 2009. He was reckoned to have sold at least 12 million albums either as part of a team or on his own. Almost all of his latter-day bands were called, with a certain internal logic, The Jeff Beck Group.

If you want to know what all the fuss was about with Beck, you could do worse than to watch the YouTube clip of his performance at that 2009 event. Incredible. Strolling out all in white, he first revs up “Beck’s Bolero” from the Truth album, coaxing a whole barrage of shrieking effects from the guitar, a chameleon on a tightrope, then in an instant flips back to the bluesy crunch of Led Zeppelin’s “Immigrant Song” with Zep’s own Jimmy Page, who wrote the number, content to stand behind him playing rhythm. In rock music terms, that’s akin to having Mozart serve as your page-turner while you handle the really tricky part of the performance. Jeff Beck was that good.

Like his music, Beck himself was sometimes hard to fathom. Rarely interviewed, he wasn’t one to open his beautiful home to Hello! magazine, or tell us about his inspiring path to sobriety. He married twice and had no children. There’s evidence to suggest he could be a bit cantankerous, and photos often show him with a Clint Eastwood squint, or sometimes the fixed smile of a man who’s just been slipped a note telling him that his dinner guest is a schizophrenic ax murderer. On the other hand, Beck could do a nice line in self-deprecation, as witnessed by the sleeve notes on one of his solo albums: “It’s almost impossible to come up with anything totally original – so I haven’t.” Anyone familiar with the classic 1984 Spinal Tap mockumentary need only think of that band’s moody, shag-haired Nigel Tufnel, though with actual musical prowess, to get some of the flavor.

Over the years, Beck collaborated with everyone from Stevie Wonder to Tina Turner to Ozzy Osbourne. His last project was a characteristically eccentric album called 18, which featured Johnny Depp on vocals, released just a month after the protracted train wreck of the Depp-Amber Heard domestic abuse case. Whatever else you can say about Beck, he wasn’t one to take the road most traveled, or to retreat into coffee-table blues. “Interesting things happen,” he once said, “when you’re open to trying something different.”

I interviewed him once, if you can call it that, backstage — let’s be honest, more of a corridor — at Ronnie Scott’s Club in London. I asked him if it was true he’d said no to the Rolling Stones when they asked him to join the band in 1975. Beck gave me his unblinking death-ray stare for a second, then said, “Can you see me playing ‘Honky Tonk Women’ on stage every night for the rest of my life?” We stood there in silence for a moment. “I’m too easily bored,” Beck added, suddenly breaking into a wide grin. “And besides, the old farts couldn’t afford me.”