Michael Myers has always occupied a curious space among horror icons. “The Shape,” ever since he first appeared in 1978, has been silent and implacable, a killer who acts from no clear motivation at all. Whereas Freddy Krueger and Jason Voorhees and Leatherface all possess intricate, tangled backstories, Myers began as an avatar of something else: the presence of an evil that cannot be psychologized away.

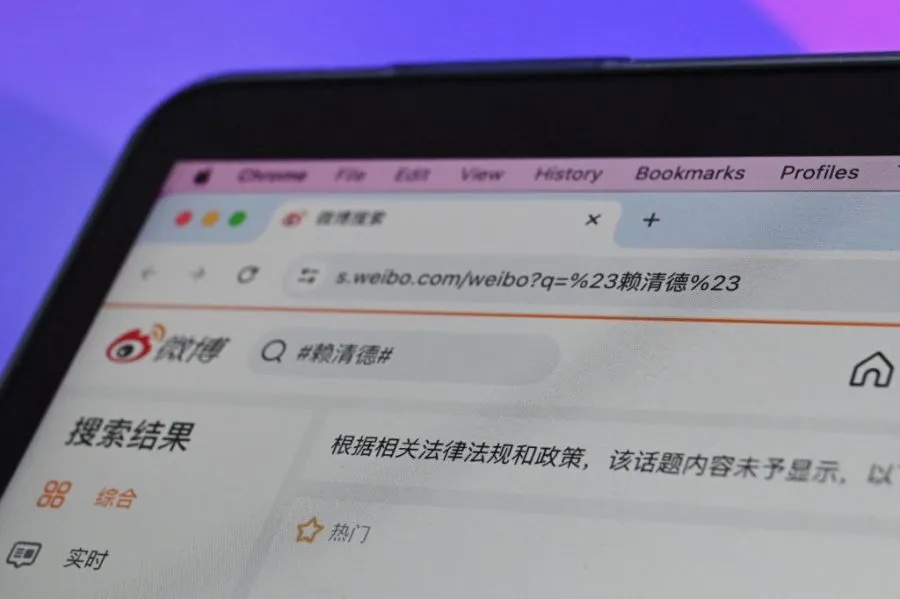

That sort of evil, as a concept, isn’t really in vogue so far as modern horror goes. Rob Zombie’s 2007 reboot tried to retool Myers’s backstory by blaming his murderous tendencies on bad parenting. And plenty of other contemporary horror flicks, from The Babadook to Smile, place psychological trauma and its consequences front-and-center. Hence, to speak of evil qua evil as something “external” — something metaphysically wrong — is to float the upsetting possibility that there may be some terrors that society can’t contain or combat.

Halloween Ends, the concluding chapter of a reboot trilogy that began in 2018, places this issue at the forefront. Picking up four years after 2021’s mediocre Halloween Kills, this aptly named finale aims, once and for all, to provide a decisive resolution to the story of babysitter-turned-survivalist Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) and the great shadow that haunts her. And on that front, it succeeds — albeit by undercutting the very strangeness of Myers the killer, and telling a very different story than the one that audiences will expect.

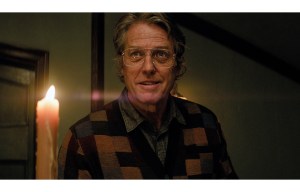

Indeed, this is barely Michael and Laurie’s story at all. It’s the story of Corey Cunningham (Rohan Campbell), a shy young man who inadvertently causes a horrendous accident leading to a child’s death. Rejected by the town of Haddonfield and demonized by everyone he knows, Corey struggles to fit in, anchored only by a burgeoning romance with Laurie’s granddaughter Allyson (Andi Matichak). As his ostracism worsens, Corey soon finds himself ensnared in the web of an old evil — weakened now, and older, but as bloody-minded and unrelenting as ever.

So, yes, Michael Myers does turn up. And he does kill. But what sort of monster is he? Or are any of us?

At the heart of this tale is the longstanding question that has followed the franchise since its origin: are human beings born into wickedness, with some incarnating the darkness in a particularly destructive way? Or are they made monsters by circumstances? The series has veered uneasily between these poles, never really settling on a single answer. Here, at last, we get a straightforward reckoning with the question — and a conclusion, of sorts.

Cultural theorist Rene Girard is perhaps best known for his analysis of the scapegoat, the designated sufferer who externalizes a community’s proclivity for internal violence and dissensus. The moral economy of the scapegoat is a sacrificial economy, one where only blood can temporarily expiate the sins of the collective. And without spoiling too much, it’s safe to say that Halloween Ends wraps with some of the most overtly Girardian images ever put to film, rendering a kind of retrospective judgment on the entire franchise. Michael Myers may hold the butcher knife but his evil is merely a projection of the seething rage and unforgiveness that churn beneath Haddonfield’s sleepy surface.

That approach may irritate those longing to see Myers back in action as an eldritch, immortal predator. But Halloween Ends is decidedly an earned conclusion, one that dares to treat its own franchise as more than just a trashy slasher saga. Director David Gordon Green, to his credit, clearly believes this story can still have something to say, something perennial — and if the cost of serious-mindedness is a slightly lower body count, so be it.

In the end, Halloween Ends is a “horror film” unlike any other, one that barely merits the descriptor. But that’s precisely why it succeeds.